Catford Bridge Rugby Football Club Memorial Pages 1

Index Introduction - page 3 Finding the records of the fallen - page 4 Enlisting in the army – joining the great fight – page 7 Recognitions and awards of the Great War - 12 Index to the memorial - 17 2

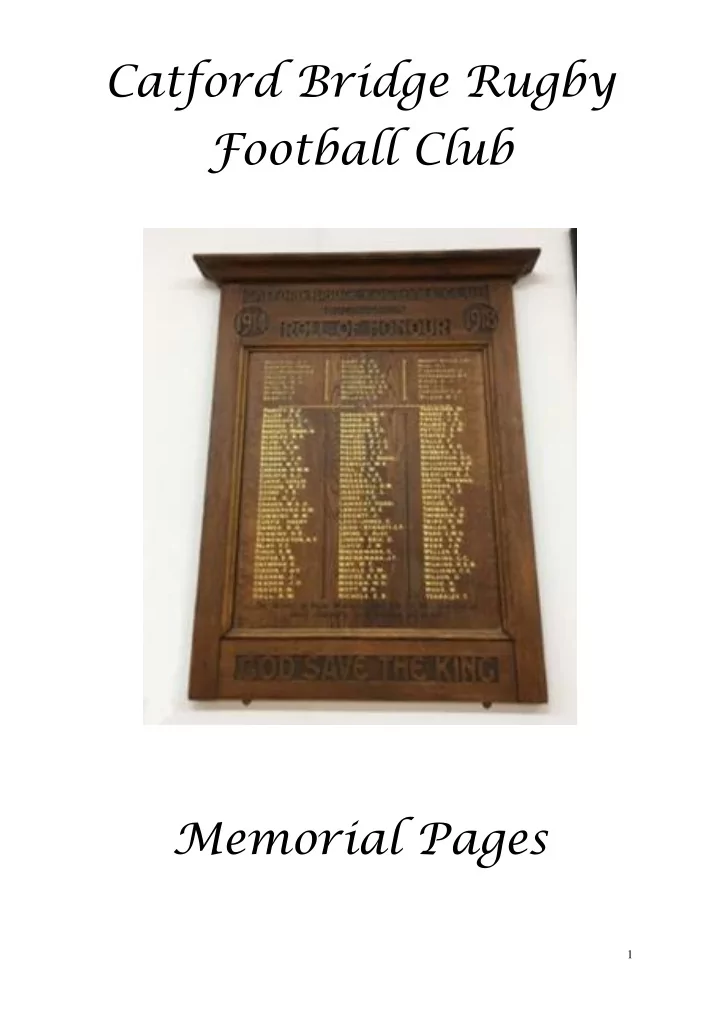

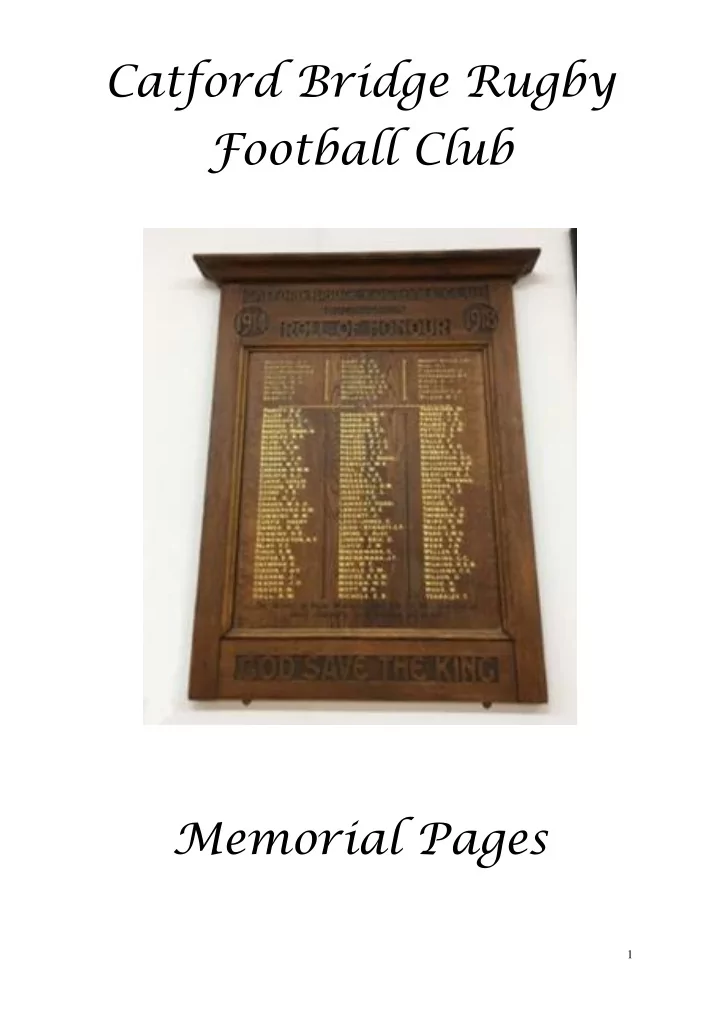

Introduction The Great War claimed the lives of many men including the 24 members of Catford Bridge Rugby Club who paid the ultimate sacrifice. The clubs memorial was originally hung at the Catford Bridge Rugby Club in Catford and following the purchase of lands at Barnet Wood Road by William (Bill) Warman, it was placed in the new clubhouse in 1956. It was removed and renovated in 2011. In 2014, following a discussion about the memorial it was suggested that those killed should be better remembered by researching their background, military history, where they died and are buried or remembered. This presentation is the result of that research. In addition to the memorial there are some pages briefly detailing the processes of enlistment and the medals and awards giving to the men. For some of these men there is family history and for others there is scant records from the 1901 or 1911 census, military records and Commonwealth War Graves Commission. To treat all these men with the same respect and dignity they are all assigned one page in this remembrance. 3

Finding the records of the fallen Researching the lives of the men of Catford Bridge Rugby Club who were killed in the Great War took many paths and presented several challenges. To begin with there are very few records from that time apart from several team photographs and fixture cards. Most of the men were easy to find through CWGC searches. The challenge was finding evidence that would link a man who might have played rugby in Catford in the years before the Great War. It is possible they may have played one game when staying in the area and were recorded in the club records. Likewise, they may have worked, trained or studied in London and played at the club (Catford Bridge was a popular club in London at this time). Some of the men are ‘closest match’ to the name on the memorial and may not be that person as proof of membership to the club is impossible. It is hoped that people reading this may have further information and the records can be updated in the future. Other challenges were around the lack of information about enlisted men as much of the records were destroyed in World War Two when the Public Records Office was damaged by bombing. Sometimes a men ’s name was not recorded correctly or misspelt in handwritten documents. Commonwealth War Graves Commission The first place to search for some basic information was the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). As all the men were killed in service there will be a recorded on their website with their age, rank and number. Also included is date of death, regimental details location of cemetery or memorial and in some case their next of kin details and head stone inscriptions. Included in the record will be the location of the cemetery and the grave or memorial of the man. The cemetery index pages can 4

provide details of the next of kin or the address of the deceased. For example, the index entry for Sidney Clark East (above) indicates the following information East, 2 nd LT. Sydney Clark. Hon. Artillery Company. 9 th Oct., 1917. Age 37. Son of the late Thomas Overton East and of Mrs. S. A. East, of Louth, Linc.; Husband of Marguerite East of “Jolimont”, London Lane, Bromley Image is from Tyne Cott Memorial, Tyne Cott Cemetery, Ypres, Belgium Not all grave indexes provide such details and so other resources are required. Medal Index Card The Medal Index Card (MIC) is a valuable means of identifying the regiment or regiments the man served in, the date of commencement of service overseas, theatre of war and medals or awards. The quality of the details did vary and following conscription less time was spent on the detail in these cards, probable due to the high volume being processed. Men’s Effects lists including their bank details and beneficiary of their will is another good source of information when tracing family members. Most of this information is available through Ancestry and other genealogy websites. 5

Other resources Ancestry (www.ancestry.co.uk) • Census 1901 & 1911 • Birth and death records • Next of kin records • Place of birth Imperial War Museum - Live of the Great War (Imperial War Museum) School Memorial pages from Google search Lewisham Memorials (lewishamwarmemorials.wikidot.com/) The Long Trial (www.longlongtrail.co.uk) 6

Enlisting into the army The expansion of the British Army from the small professional force to a vast citizen army, capable of defeating the world’s most formidable military machine, was a truly extraordinary national achievement. How was it done? What can you learn about the way your soldier joined up? Types of service available: up to the declaration of war Since 1908 the British Army had offered four forms of recruitment. A man could join the army as a professional soldier of the regular army or as a part time member of the Territorial Force or as a soldier of the Special Reserve . Finally, there was the opportunity to join the National Reserve . There was a long-running battle, with politicians and military men taking both sides, about whether Britain should have a system of national conscripted service. By 1914 this had not come about and Britain’s army was entirely voluntary. Regular army A man wishing to join the army could do so providing he passed certain physical tests and was willing to enlist for a number of years. The recruit had to be taller than 5 feet 3 inches and aged between 18 and 38 (although he could not be sent overseas until he was aged 19). He would join at the Regimental Depot or at one of its normal recruiting offices. The man had a choice over the regiment he was assigned to. He would typically join the army for a period of 7 years full time service with the colours, to be followed by another 5 in the Army Reserve. (These terms were for infantry: the other arms had slightly different ones. For example, in the artillery it was for 6 years plus 6). When war was declared there were 350,000 former soldiers on the Army Reserve, ready to be called back to fill the establishment of their regiments. Special Reserve The Special Reserve provided a form of part-time military service. It was introduced in 1908 as a means of building up a pool of trained reservists in addition to those of the regular Army Reserve. Special Reservists enlisted for 6 years and had to accept the possibility of being called up in the event of a general mobilisation and to undergo all the same conditions as men of the Army Reserve. This meant that it differed from the Territorial Force (below) in that the men could be sent overseas. Their period as a Special Reservist started with six months full-time preliminary training (paid the same as a regular) and they had 3-4 weeks training per year thereafter. A man could extend his SR service by up to four years but could not serve beyond the age of 40. A former 7

regular soldier whose period of Army Reserve obligation had been completed could also re-enlist as a Special Reservist and serve up to the age of 42. Territorial Force The Territorial Force came into existence in April 1908 as a result of the reorganisation of the former militia and other volunteer units (the Haldane Reforms). It provided an opportunity for men to join the army on a part-time basis. Territorial units of most infantry regiments and of each of the Corps (Artillery, Engineers, Medical, Service and Ordnance) were formed. For example, most county regiments of the infantry formed two Territorial battalions. These units were recruited locally and became more recognised and supported by the local community than the regulars. Recruits had a choice of regiment, but naturally the local nature of the TF meant that in general the man joined his home unit. The TF County Associations, the administration of the local TF, were planned to be a medium by which the army could be expanded in wartime. Men trained at weekends or in the evenings and went away to a summer camp. Territorials were not obliged to serve overseas, but were enlisted on the basis that in the event of war they could be called upon for full-time service (“embodied”). The physical c riteria for joining the Terriers was the same as for the Regular army but the lower age limit was 17. National Reserve Members of the National Reserve were trained officers and men who had no further obligation for military service. Their names were placed on a register and they could be mobilised in the event of imminent national danger. The register was maintained by the County Association that also organised their Territorial Force. The was no age limit for joining or leaving the National Reserve. National Reservists were not required to undertake any definite liability; however, they were invited to sign an honourable obligation to present themselves for service if and when required. They could be used to reinforce existing units of the Army or the TF once it had mobilised and could also be used, among other things, to strengthen Garrisons (such as those in India) or guard vulnerable strategic points across the country. 8

Recommend

More recommend