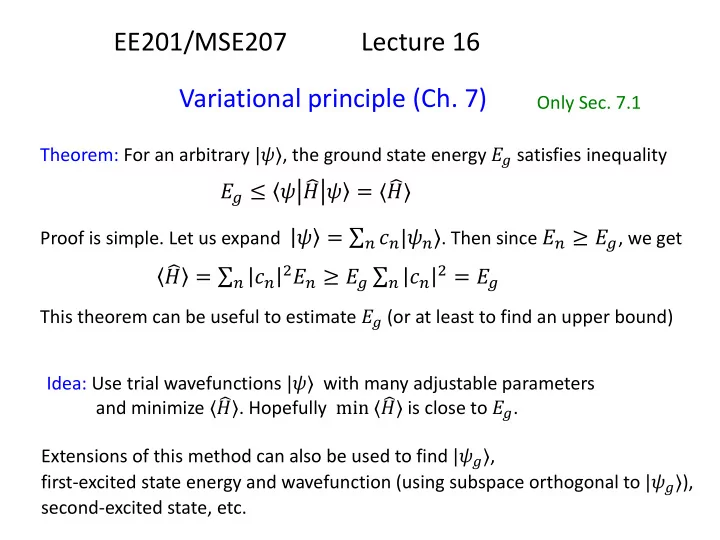

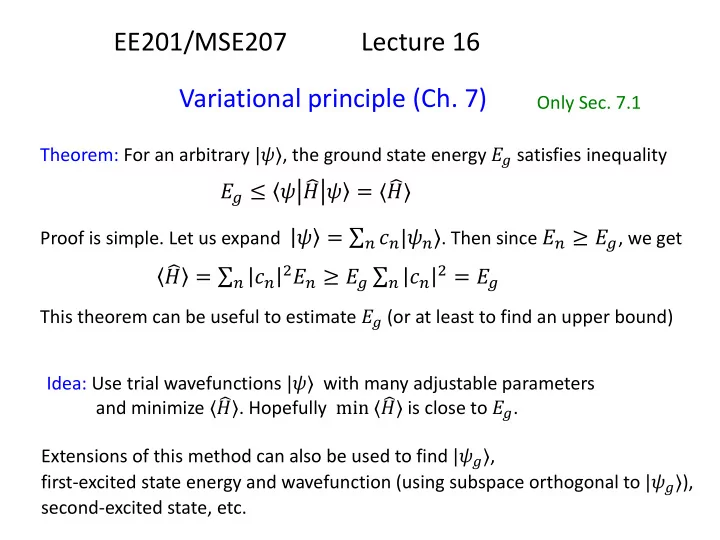

EE201/MSE207 Lecture 16 Variational principle (Ch. 7) Only Sec. 7.1 Theorem: For an arbitrary |𝜔〉 , the ground state energy 𝐹 satisfies inequality 𝐹 ≤ 𝜔 𝐼 𝜔 = 〈 𝐼〉 Proof is simple. Let us expand 𝜔 = 𝑜 𝑑 𝑜 |𝜔 𝑜 〉 . Then since 𝐹 𝑜 ≥ 𝐹 , we get 𝐼 = 𝑜 𝑑 𝑜 2 𝐹 𝑜 ≥ 𝐹 𝑜 𝑑 𝑜 2 = 𝐹 This theorem can be useful to estimate 𝐹 (or at least to find an upper bound) Idea: Use trial wavefunctions |𝜔〉 with many adjustable parameters and minimize 〈 𝐼〉 . Hopefully min 〈 𝐼〉 is close to 𝐹 . Extensions of this method can also be used to find |𝜔 〉 , first-excited state energy and wavefunction (using subspace orthogonal to |𝜔 〉 ), second-excited state, etc.

EE201/MSE207 Lecture 16 Band structure (back to Ch. 5) Band structure for electrons is a consequence of a periodic potential in a lattice (due to periodic arrangement of atoms). For simplicity let us consider 1D case 𝑊 𝑦 + 𝑏 = 𝑊(𝑦) (periodic with lattice constant 𝑏 ) Bloch’s theorem: If 𝑊 𝑦 + 𝑏 = 𝑊(𝑏) , then for an eigenstate of energy 𝜔(𝑦 + 𝑏) = 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑏 𝜔 𝑦 (almost periodic, “ quasimomentum ” ℏ𝐿 ) Therefore 𝜔 𝑦 = 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑦 𝜔(𝑦) , 𝜔 𝑦 + 𝑏 = 𝜔(𝑦) with periodic 𝜔(𝑦) Proof Introduce displacement operator 𝐸 , so that 𝐸𝑔(𝑦) = 𝑔(𝑦 + 𝑏) . It commutes with Hamiltonian, 𝐸, 𝐼 = 0 , therefore common eigenfunctions. 𝜔 𝑦 + 𝑏 = 𝜇 𝜔 𝑦 If 𝜇 ≠ 1 , then 𝜔 would increase or decrease exponentially Therefore 𝜇 = 1 , can denote 𝜇 = 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑏 .

Periodic boundary condition for Bloch’s theorem 𝜔(𝑦 + 𝑏) = 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑏 𝜔 𝑦 ⇒ 𝑊 𝑦 + 𝑏 = 𝑊 𝑏 Usually people use periodic boundary condition in using Bloch’s theorem 𝜔 𝑦 + 𝑂𝑏 = 𝜔(𝑦) for 𝑂 ⋙ 1 atoms in a (1D) sample Why? Because it does not matter, but makes calculations simpler 𝐿 = 2𝜌𝑜 𝑂𝑏 , 𝑜 = 0, ±1, ±2, … Then This gives 𝑂 different values of 𝐿 (the same 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑏 if Δ𝑜 = 𝑂 ): 𝑂 states in a band for 𝑂 atoms Since 𝑂 is very large, 𝐿 is almost continuous.

Simple example: “Dirac comb” 𝑂 “atoms” Dirac comb: 𝑂 𝑊 𝑦 = 𝛽 𝑘=1 𝜀(𝑦 − 𝑘𝑏) (wrapped around) − ℏ 2 𝑒 2 𝜔 𝑦 + 𝑊 𝑦 𝜔 𝑦 = 𝐹 𝜔 𝑦 𝑒𝑦 2 2𝑛 0 < 𝑦 < 𝑏 ⇒ 𝜔 𝑦 = 𝐵 sin(𝑙𝑦) + 𝐶 cos 𝑙𝑦 , 𝑙 = 2𝑛𝐹/ℏ From Bloch’s theorem we know that at −𝑏 < 𝑦 < 0 , 𝜔 𝑦 = 𝑓 −𝑗𝐿𝑏 [𝐵 sin 𝑙(𝑦 + 𝑏) + 𝐶 cos 𝑙(𝑦 + 𝑏) ] 𝐶 = 𝑓 −𝑗𝐿𝑏 [𝐵 sin 𝑙𝑏 + 𝐶 cos(𝑙𝑏)] 𝜔 0 + 0 = 𝜔 0 − 0 ⇒ 𝜔 ′ 0 + 0 − 𝜔 ′ 0 − 0 = ( 2𝑛𝛽 ℏ 2 ) 𝜔(0) ⇒ 𝑙𝐵 − 𝑓 −𝑗𝐿𝑏 [𝑙𝐵 cos 𝑙𝑏 − 𝑙𝐶 sin(𝑙𝑏) ] = ( 2𝑛𝛽 ℏ 2 ) 𝐶 From these two equations we find (eliminating 𝐵 and 𝐶 ) cos 𝐿𝑏 = cos 𝑙𝑏 + 𝑛𝛽𝑏 sin(𝑙𝑏) ℏ 2 𝑙𝑏

Dirac comb (cont.) 𝑂 𝑊 𝑦 = 𝛽 𝑘=1 𝜀(𝑦 − 𝑘𝑏) cos 𝐿𝑏 = cos 𝑙𝑏 + 𝑛𝛽𝑏 sin(𝑙𝑏) ℏ 2 𝑙𝑏 𝑂 states 𝐿𝑏 = 2𝜌𝑜 𝑂 gap 𝑂 states gap gap gap gap 2 nd band 1 st band 3 rd band 𝑂 states 𝑛𝛽𝑏 = 10 ℏ 2 𝑂 states 𝑙𝑏 (∝ 𝐹) 𝑂 states per band ( × 2 spin) Gaps become smaller, eventually continuum

Bands Gaps become smaller, eventually continuum If one electron per atom ( 𝑟 = 1 ), then half a band is filled (good conductor) If 𝑟 = 2 , then one band is filled completely (insulator or semiconductor; cannot slightly excite electrons) If 𝑟 = 3 , then 1.5 bands are filled (good conductor) If 𝑟 = 4 , then again insulator or semiconductor Etc. Metals usually have 𝑟 = 1 𝑂 states per band ( × 2 spin)

Bands (cont.) ∝ 𝐹 cos 𝐿𝑏 = . . . ℏ𝐿 is quasimomentum (behaves as momentum) −𝜌/𝑏 𝜌/𝑏 2𝜌/𝑏 (Brillouin zone) Periodic: 2𝜌/𝑏 𝐹 = ℏ 2 𝑙 2 For a free particle 2𝑛 Define effective mass 𝑛 eff via Δ𝐹 = ℏ 2 𝐿 2 Δ𝐹 = ℏ 2 (Δ𝐿) 2 or even 2𝑛 eff 2𝑛 eff 𝑒𝐿 2 = ℏ 2 𝑒 2 𝐹 (similar to bands in semiconductors) or even 𝑛 eff

Quasimomentum ℏ𝐿 behaves as momentum Let us add small force 𝐺 (e.g., due to electric field acting on electron, 𝐺 = −𝑓ℰ ). Then Δ𝑊 = −𝐺𝑦 and therefore 𝐹 → 𝐹 − 𝐺𝑦 (for the same 𝐿 ). From Bloch’s theorem we know 𝜔 𝑦 = 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑦 𝜔 𝐿 (𝑦) ∝ 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑦 on the large scale Adding time dependence, we get (on the large scale) Ψ 𝑦, 𝑢 ∝ 𝑓 𝑗𝐿𝑦 𝑓 −𝑗 𝐹−𝐺𝑦 𝑢 = 𝑓 𝑗 𝐿+ 𝐺𝑢 ℏ 𝑦 𝑓 −𝑗𝐹𝑢/ℏ ℏ 𝐿 → 𝐿 + 𝐺 𝑒(ℏ𝐿) ℏ 𝑢 ⇒ = 𝐺 It means 𝑒𝑢 We see that ℏ𝐿 behaves as momentum (so named quasimomentum) (for validity of this approach we need very small 𝐺 ) Actually, significant oversimplification in this approach; this rather a hint. 𝑢 ′ ℏ) 𝑒𝑢 ′ 𝑢 𝐹(𝐿+𝐺 𝐺𝑢 ℏ)𝑦 𝑓 − 𝑗 ℏ 𝑓 𝑗(𝐿+ 𝜔 𝐿+𝐺 𝑢 ℏ (𝑦) More rigorously, 0 is an approximate solution of SE (straightforward to check). Also, makes sense for energy change: 𝐺𝑤 𝑠 = ℏ 𝑒𝐿 ℏ 𝑒𝐿 = 𝑒𝐹 𝑒𝐹 𝑒𝑢 . 𝑒𝑢

End of material included into the final exam Following lectures are important, but not needed for the exam

Recommend

More recommend