Examples of local weak limits Note: graphs must be sparse , i.e. | E | ≍ | V | ◮ G n = box of size n × . . . × n in Z d L = dirac at ( Z d , 0) ◮ G n = random d − regular graph on n nodes L = dirac at the d − regular infinite rooted tree enyi graph with p n = c ◮ G n = Erd˝ os-R´ n on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree Poisson(c) ◮ G n = random graph with degree distribution π on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree distribution π ◮ G n = uniform random tree on n nodes

Examples of local weak limits Note: graphs must be sparse , i.e. | E | ≍ | V | ◮ G n = box of size n × . . . × n in Z d L = dirac at ( Z d , 0) ◮ G n = random d − regular graph on n nodes L = dirac at the d − regular infinite rooted tree enyi graph with p n = c ◮ G n = Erd˝ os-R´ n on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree Poisson(c) ◮ G n = random graph with degree distribution π on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree distribution π ◮ G n = uniform random tree on n nodes L = Infinite Skeleton Tree (Grimmett, 1980)

Examples of local weak limits Note: graphs must be sparse , i.e. | E | ≍ | V | ◮ G n = box of size n × . . . × n in Z d L = dirac at ( Z d , 0) ◮ G n = random d − regular graph on n nodes L = dirac at the d − regular infinite rooted tree enyi graph with p n = c ◮ G n = Erd˝ os-R´ n on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree Poisson(c) ◮ G n = random graph with degree distribution π on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree distribution π ◮ G n = uniform random tree on n nodes L = Infinite Skeleton Tree (Grimmett, 1980) ◮ G n = preferential attachment graph on n nodes

Examples of local weak limits Note: graphs must be sparse , i.e. | E | ≍ | V | ◮ G n = box of size n × . . . × n in Z d L = dirac at ( Z d , 0) ◮ G n = random d − regular graph on n nodes L = dirac at the d − regular infinite rooted tree enyi graph with p n = c ◮ G n = Erd˝ os-R´ n on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree Poisson(c) ◮ G n = random graph with degree distribution π on n nodes L = law of a Galton-Watson tree with degree distribution π ◮ G n = uniform random tree on n nodes L = Infinite Skeleton Tree (Grimmett, 1980) ◮ G n = preferential attachment graph on n nodes L = Polya-point graph (Berger-Borgs-Chayes-Sabery, 2009)

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . | V |

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . Asymptotics when G is large ? | V |

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . Asymptotics when G is large ? | V | n , c � � Conjecture (Bauer-Golinelli 2001). For G n : Erd˝ os-R´ enyi , n λ ∗ + e − c λ ∗ + c λ ∗ e − c λ ∗ − 1 , µ G n ( { 0 } ) − − − → n →∞ where λ ∗ ∈ [0 , 1] is the smallest root of λ = e − ce − c λ .

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . Asymptotics when G is large ? | V | n , c � � Conjecture (Bauer-Golinelli 2001). For G n : Erd˝ os-R´ enyi , n λ ∗ + e − c λ ∗ + c λ ∗ e − c λ ∗ − 1 , µ G n ( { 0 } ) − − − → n →∞ where λ ∗ ∈ [0 , 1] is the smallest root of λ = e − ce − c λ . Theorem (Bordenave-Lelarge-S., 2011)

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . Asymptotics when G is large ? | V | n , c � � Conjecture (Bauer-Golinelli 2001). For G n : Erd˝ os-R´ enyi , n λ ∗ + e − c λ ∗ + c λ ∗ e − c λ ∗ − 1 , µ G n ( { 0 } ) − − − → n →∞ where λ ∗ ∈ [0 , 1] is the smallest root of λ = e − ce − c λ . Theorem (Bordenave-Lelarge-S., 2011) 1. G n → L = ⇒ µ G n ( { 0 } ) → µ L ( { 0 } ).

An illustration: the nullity of large graphs µ G ( { 0 } ) = dim ker ( A G ) . Asymptotics when G is large ? | V | n , c � � Conjecture (Bauer-Golinelli 2001). For G n : Erd˝ os-R´ enyi , n λ ∗ + e − c λ ∗ + c λ ∗ e − c λ ∗ − 1 , µ G n ( { 0 } ) − − − → n →∞ where λ ∗ ∈ [0 , 1] is the smallest root of λ = e − ce − c λ . Theorem (Bordenave-Lelarge-S., 2011) 1. G n → L = ⇒ µ G n ( { 0 } ) → µ L ( { 0 } ). 2. When L = Galton-Watson ( π ), f ′ (1) λλ ∗ + f (1 − λ ) + f (1 − λ ∗ ) − 1 � � µ L ( { 0 } ) = min , λ = λ ∗∗ n π n z n and λ ∗ = f ′ (1 − λ ) / f ′ (1). where f ( z ) = �

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only.

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − →

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size.

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ).

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ). ◮ Examples:

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ). ◮ Examples: number of spanning trees (Lyons, 2005),

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ). ◮ Examples: number of spanning trees (Lyons, 2005), spectrum and rank (Bordenave-Lelarge-S, 2011),

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ). ◮ Examples: number of spanning trees (Lyons, 2005), spectrum and rank (Bordenave-Lelarge-S, 2011), matching polynomial (idem, 2013),

Continuity with respect to local weak convergence ◮ In the sparse regime, many important graph parameters Φ are essentially determined by the local geometry only. ◮ This can be rigorously formalized by a continuity theorem: loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Φ( G n ) − n →∞ Φ( L ) − − → ◮ Algorithmic implication: Φ is efficiently approximable via local distributed algorithms, independently of network size. ◮ Analytic implication: Φ admits a limit along most sparse graph sequences. The distributional self-similarity of L may even allow for an explicit determination of Φ( L ). ◮ Examples: number of spanning trees (Lyons, 2005), spectrum and rank (Bordenave-Lelarge-S, 2011), matching polynomial (idem, 2013), Ising models (Dembo-Montanari-Sun, 2013)...

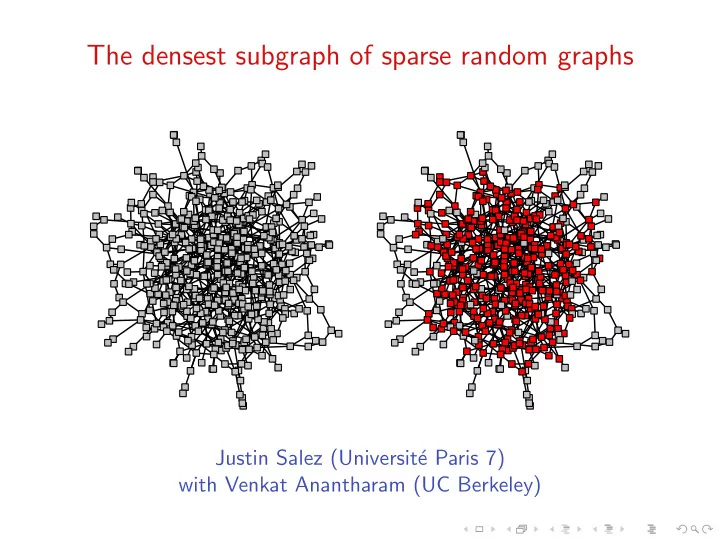

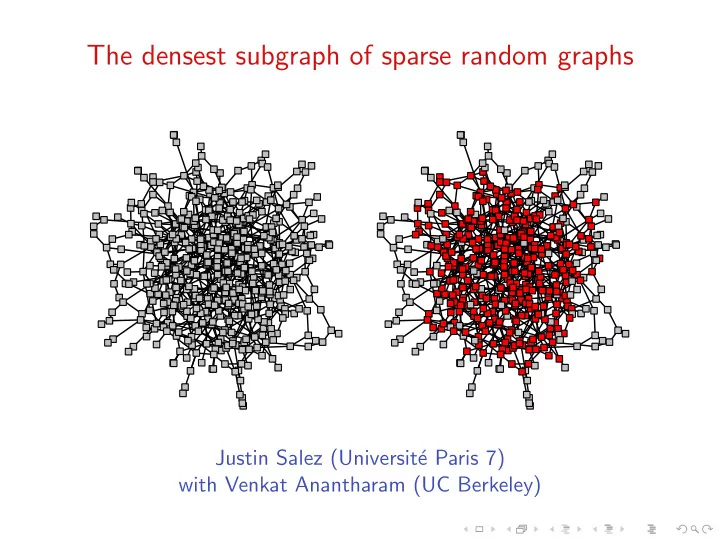

The densest subgraph problem

The densest subgraph problem Fix a finite graph G = ( V , E )

The densest subgraph problem Fix a finite graph G = ( V , E ) Densest subgraph : H ⋆ = argmax � � | E ( H ) | | H | : H ⊆ V

The densest subgraph problem Fix a finite graph G = ( V , E ) Densest subgraph : H ⋆ = argmax � � | E ( H ) | | H | : H ⊆ V � � Maximum subgraph density : ̺ ⋆ = max | E ( H ) | | H | : H ⊆ V

The densest subgraph problem Fix a finite graph G = ( V , E ) Densest subgraph : H ⋆ = argmax � � | E ( H ) | | H | : H ⊆ V � � Maximum subgraph density : ̺ ⋆ = max | E ( H ) | = 17 | H | : H ⊆ V 10

The densest subgraph problem on large sparse graphs

The densest subgraph problem on large sparse graphs

The densest subgraph problem on large sparse graphs

Load balancing

Load balancing An allocation on G is a function θ : � E → [0 , 1] satisfying θ ( i , j ) + θ ( j , i ) = 1

Load balancing An allocation on G is a function θ : � E → [0 , 1] satisfying θ ( i , j ) + θ ( j , i ) = 1 The induced load at i ∈ V is � ∂θ ( i ) = θ ( j , i ) j ∼ i

Load balancing An allocation on G is a function θ : � E → [0 , 1] satisfying θ ( i , j ) + θ ( j , i ) = 1 The induced load at i ∈ V is � ∂θ ( i ) = θ ( j , i ) j ∼ i The allocation is balanced if for each ( i , j ) ∈ � E ∂θ ( i ) < ∂θ ( j ) = ⇒ θ ( i , j ) = 0

From local to global optimality

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent:

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes �

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes � 3. θ minimizes � i f ( ∂θ ( i )) for any convex function f : R → R .

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes � 3. θ minimizes � i f ( ∂θ ( i )) for any convex function f : R → R . Corollary 1. Balanced allocations always exist.

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes � 3. θ minimizes � i f ( ∂θ ( i )) for any convex function f : R → R . Corollary 1. Balanced allocations always exist. Corollary 2. They all induce the same loads ∂θ : V → [0 , ∞ ).

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes � 3. θ minimizes � i f ( ∂θ ( i )) for any convex function f : R → R . Corollary 1. Balanced allocations always exist. Corollary 2. They all induce the same loads ∂θ : V → [0 , ∞ ). Corollary 3. Balanced loads solve the densest subgraph problem:

From local to global optimality Claim. For an allocation θ , the following are equivalent: 1. θ is balanced i ( ∂θ ( i )) 2 . 2. θ minimizes � 3. θ minimizes � i f ( ∂θ ( i )) for any convex function f : R → R . Corollary 1. Balanced allocations always exist. Corollary 2. They all induce the same loads ∂θ : V → [0 , ∞ ). Corollary 3. Balanced loads solve the densest subgraph problem: i ∈ V ∂θ ( i ) = ̺ ⋆ ∂θ ( i ) = H ⋆ max and argmax i ∈ V

Example

Example 5 10 5 10 5 1 10 5 2 9 8 3 10 8 5 6 8 5 8 9 4 4 7 2 5 2 7 5 8 5 3 5 5 2 2 5 10 3 7 5 5 7 3 10 1 5 5 7 10 1 6 10 2 3 2 8 5 10 9 10 10 8 5 10 5 10 10 5 10 10 5 5

Example 1.5 1.6 1.6 1 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.7 1.5 1.5 1 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.5 1.7 1.5 1 1.7 1.5 1.5 1 1.5 1.5

Example 1.5 1.6 1.6 1 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.7 1.5 1.5 1 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.5 1.7 1.5 1 1.7 1.5 1.5 1 1.5 1.5

How do those ‘densities” look on a large sparse graph ?

How do those ‘densities” look on a large sparse graph ?

How do those ‘densities” look on a large sparse graph ?

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 3

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 3 | V | = 100

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 3 | V | = 100 | V | = 10000

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 4

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 4 | V | = 100

Density profile of a random graph with average degree 4 | V | = 100 | V | = 10000

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990)

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990) ∂ Θ( G , o ) : load induced at o by any balanced allocation on G .

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990) ∂ Θ( G , o ) : load induced at o by any balanced allocation on G . Define the density profile of G = ( V , E ) as 1 � Λ G = δ ∂ Θ( G , o ) ∈ P ( R ) . | V | o ∈ V

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990) ∂ Θ( G , o ) : load induced at o by any balanced allocation on G . Define the density profile of G = ( V , E ) as 1 � Λ G = δ ∂ Θ( G , o ) ∈ P ( R ) . | V | o ∈ V n , c � � Conjecture: G n Erd˝ os-R´ enyi ; c fixed, n → ∞ n

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990) ∂ Θ( G , o ) : load induced at o by any balanced allocation on G . Define the density profile of G = ( V , E ) as 1 � Λ G = δ ∂ Θ( G , o ) ∈ P ( R ) . | V | o ∈ V n , c � � Conjecture: G n Erd˝ os-R´ enyi ; c fixed, n → ∞ n 1. Λ G n concentrates around a deterministic Λ ∈ P ( R )

The conjecture (Hajek, 1990) ∂ Θ( G , o ) : load induced at o by any balanced allocation on G . Define the density profile of G = ( V , E ) as 1 � Λ G = δ ∂ Θ( G , o ) ∈ P ( R ) . | V | o ∈ V n , c � � Conjecture: G n Erd˝ os-R´ enyi ; c fixed, n → ∞ n 1. Λ G n concentrates around a deterministic Λ ∈ P ( R ) P 2. ̺ ⋆ ( G n ) − n →∞ sup { t ∈ R : Λ( t , + ∞ ) > 0 } − − →

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs Theorem. Assume that L [deg( G , o )] < ∞ .

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs Theorem. Assume that L [deg( G , o )] < ∞ . Then, P ( R ) loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Λ G n − n →∞ Λ L − − →

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs Theorem. Assume that L [deg( G , o )] < ∞ . Then, P ( R ) loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Λ G n − n →∞ Λ L − − → where Λ L is the solution to a certain optimization problem on L .

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs Theorem. Assume that L [deg( G , o )] < ∞ . Then, P ( R ) loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Λ G n − n →∞ Λ L − − → where Λ L is the solution to a certain optimization problem on L . � R ( x − t ) + Λ L ( dx ) Specifically, the excess function Φ: t �→

Result 1 : the density profile of sparse graphs Theorem. Assume that L [deg( G , o )] < ∞ . Then, P ( R ) loc . G n − n →∞ L − − → = ⇒ Λ G n − n →∞ Λ L − − → where Λ L is the solution to a certain optimization problem on L . � R ( x − t ) + Λ L ( dx ) solves Specifically, the excess function Φ: t �→ � �� � � 1 Φ( t ) = max 2 L f ( G , i ) ∧ f ( G , o ) − t L [ f ( G , o )] f : G ⋆ → [0 , 1] i ∼ o

Result 2 : maximum subgraph density of sparse graphs

Recommend

More recommend