Effective plots to assess bias and precision in method comparison - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Effective plots to assess bias and precision in method comparison studies Bern, November, 2016 Patrick Taff, PhD Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (IUMSP) University of Lausanne, Switzerland Patrick.Taffe@chuv.ch

Effective plots to assess bias and precision in method comparison studies Bern, November, 2016 Patrick Taffé, PhD Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (IUMSP) University of Lausanne, Switzerland Patrick.Taffe@chuv.ch ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������

Outline • Bland & Altman’s limits of agreement method (1986) • Extension to proportional bias and heteroscedasticity (1999) • A new methodology to quantify bias and precision • Illustration with a simulated example ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 2

How to measure agreement between two measurement methods ? Ex: blood pressure STATISTICAL METHODS FOR ASSESSING AGREEMENT BETWEEN TWO METHODS OF CLINICAL MEASUREMENT � ����������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �� �����!�������"#$�%&�'�������(������������������������������&�����������&������ � ��������)��� *��+�,��+����������������*����������-� � . ������ ��#/01'� i: 23$42#35� � Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two ... www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2868172 Cited by 35451 - by JM Bland - 1986 - Related articles Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307-10. ������������������������ ���������������������������������������������������� ����� ����������� . Bland JM, Altman DG. ������������������������������������������������������������������ 3

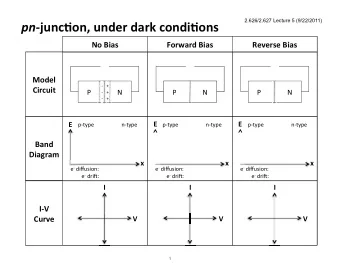

Bland & Altman (1986) : They wanted a measure of agreement which was easy to estimate and to interpret for a measurement on an individual patient. An obvious starting point was a plot of the differences versus the mean of the measurements by the two methods : ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 4

The bias (differential bias) between the two measurement methods is estimated by the mean difference : bias mean ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 5

If the differences are normally distributed, we would expect about 95% of the differences to lie between the mean +- 1.96*SD, the so called limits of agreement (LoA) (Bland & Altman, 1986): ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 6

The decision about what is acceptable agreement is a clinical one: We can see that the blood pressure machine (S) may give values between 55mmHg above the sphygmomanometer (J) reading to 22mmHg below it, => such differences would be unacceptable for clinical purposes ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 7

However, these estimates are meaningful only if we can assume bias and variability are uniform throughout the range of measurement, assumptions which can be checked graphically: => assumptions approximatively met ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 8

In some cases the variability of the measurements increases with the magnitude of the latent trait (heteroscedasticity), as well as with the mean difference (proportional bias): Plasma volume data (Bland & Altman, 1999) 18 14 difference: Nadler-Hurley 10 6 2 -2 60 80 100 120 140 average: (Nadler+Hurley)/2 Plasma volume expressed in percentage of normal value: as measured by Nadler and Hurley ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 9

In this case, a linear regression of the differences on the averages can be estimated along with the LoA (Bland & Altman, 1999): Plasma volume data (Bland & Altman, 1999) 18 difference: Nadler-Hurley 14 10 6 2 -2 60 80 100 120 140 average: (Nadler+Hurley)/2 difference linear prediction upper 95% LoA lower 95% LoA Plasma volume expressed in percentage of normal value: as measured by Nadler and Hurley ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 10

In that case, the LoA are more difficult to interpret Plasma volume data (Bland & Altman, 1999) 18 (width not constant), difference: Nadler-Hurley 14 10 6 2 -2 and more importantly, 60 80 100 120 140 average: (Nadler+Hurley)/2 difference linear prediction upper 95% LoA lower 95% LoA there are settings where Bland & Altman’s plots are misleading ! Indeed, we will show that when variances of the measurement errors of the two methods are different, Bland and Altman’s plots may be misleading5 ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 11

Simulated examples where the regression line shows an upward or a downward trend but there is no biasJ LoA mu_Y1=9.61 mu_Y2=9.99 sig2_y1=60.56 sig2_y2=34.69 sig2_e1=26.25 sig2_e2=1.00 biais = 0.38 20 10 difference: y1-y2 LoA mu_Y1=10.33 mu_Y2=10.28 sig2_y1=34.68 sig2_y2=69.12 sig2_e1=0.95 sig2_e2=36.41 biais = -0.04 0 20 -10 10 difference: y1-y2 -20 0 -10 0 10 20 30 average: (y1+y2)/2 -10 difference Linear prediction upper2 lower2 zero -20 0 10 20 30 LoA average: (y1+y2)/2 mu_Y1=23.77 mu_Y2=24.05 sig2_y1=60.90 sig2_y2=84.75 sig2_e1=3.53 sig2_e2=30.44 biais = 0.28 difference Linear prediction upper2 lower2 20 zero 10 difference: y1-y2 0 -10 ����� -20 ������������������������������������������������������������������ 0 10 20 30 40 50 average: (y1+y2)/2 12

or a zero slope and there is a biasJ LoA mu_Y1=23.74 mu_Y2=23.73 sig2_y1=101.30 sig2_y2=97.90 sig2_e1=3.47 sig2_e2=23.93 biais = -0.01 20 10 difference: y1-y2 0 -10 LoA mu_Y1=25.99 mu_Y2=26.05 sig2_y1=93.75 sig2_y2=92.50 sig2_e1=5.02 sig2_e2=25.73 biais = 0.06 -20 20 0 10 20 30 40 50 average: (y1+y2)/2 10 difference: y1-y2 0 -10 -20 0 10 20 30 40 50 average: (y1+y2)/2 ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 13

Therefore, the goal of my presentation is to introduce a new methodology for the evaluation of the agreement between two methods of measurement, where the first is the ������������������ and the other the ����������� to be evaluated: Effective plots to assess bias and precision in method comparison studies Patrick Taffé Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Lausanne, Switzerland Patrick.Taffe@chuv.ch Accepted September 2015, online October 2016 ����� ������������������������������������������������������������������ 14

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.