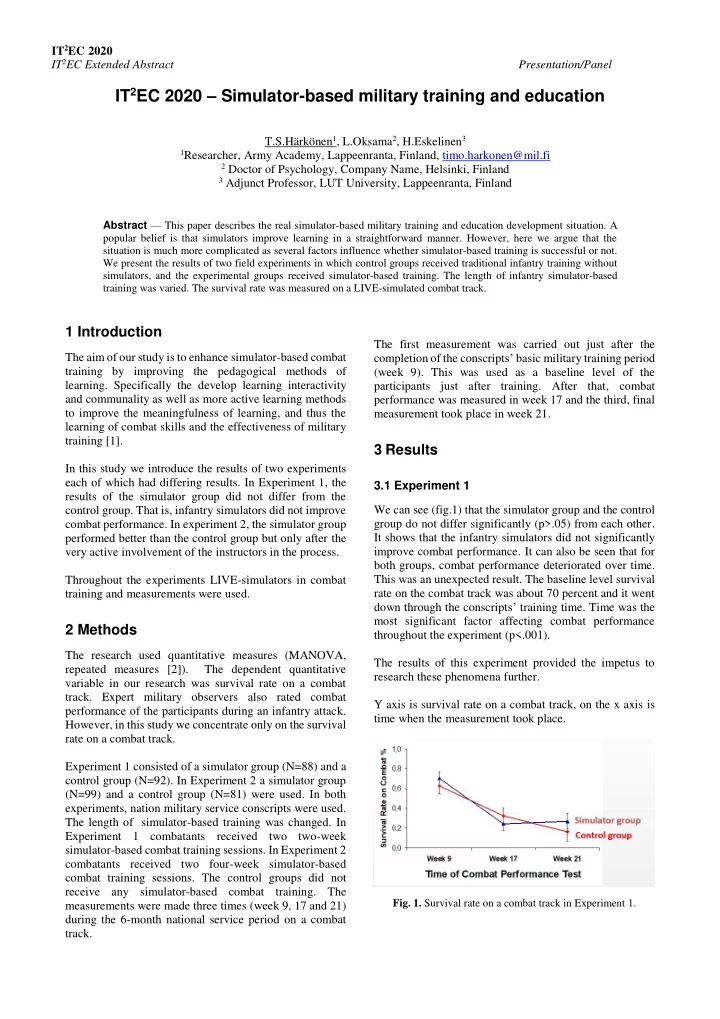

IT 2 EC 2020 IT 2 EC Extended Abstract Presentation/Panel IT 2 EC 2020 – Simulator-based military training and education T.S.Härkönen 1 , L.Oksama 2 , H.Eskelinen 3 1 Researcher, Army Academy, Lappeenranta, Finland, timo.harkonen@mil.fi 2 Doctor of Psychology, Company Name, Helsinki, Finland 3 Adjunct Professor, LUT University, Lappeenranta, Finland Abstract — This paper describes the real simulator-based military training and education development situation. A popular belief is that simulators improve learning in a straightforward manner. However, here we argue that the situation is much more complicated as several factors influence whether simulator-based training is successful or not. We present the results of two field experiments in which control groups received traditional infantry training without simulators, and the experimental groups received simulator-based training. The length of infantry simulator-based training was varied. The survival rate was measured on a LIVE-simulated combat track. 1 Introduction The first measurement was carried out just after the completion of the conscript s’ basic military training period The aim of our study is to enhance simulator-based combat training by improving the pedagogical methods of (week 9). This was used as a baseline level of the learning. Specifically the develop learning interactivity participants just after training. After that, combat and communality as well as more active learning methods performance was measured in week 17 and the third, final to improve the meaningfulness of learning, and thus the measurement took place in week 21. learning of combat skills and the effectiveness of military training [1]. 3 Results In this study we introduce the results of two experiments each of which had differing results. In Experiment 1, the 3.1 Experiment 1 results of the simulator group did not differ from the We can see (fig.1) that the simulator group and the control control group. That is, infantry simulators did not improve combat performance. In experiment 2, the simulator group group do not differ significantly (p>.05) from each other. It shows that the infantry simulators did not significantly performed better than the control group but only after the very active involvement of the instructors in the process. improve combat performance. It can also be seen that for both groups, combat performance deteriorated over time. Throughout the experiments LIVE-simulators in combat This was an unexpected result. The baseline level survival rate on the combat track was about 70 percent and it went training and measurements were used. down through the conscript s’ training time. Time was the most significant factor affecting combat performance 2 Methods throughout the experiment (p<.001). The research used quantitative measures (MANOVA, The results of this experiment provided the impetus to repeated measures [2]). The dependent quantitative research these phenomena further. variable in our research was survival rate on a combat track. Expert military observers also rated combat Y axis is survival rate on a combat track, on the x axis is performance of the participants during an infantry attack. time when the measurement took place. However, in this study we concentrate only on the survival rate on a combat track. Experiment 1 consisted of a simulator group (N=88) and a control group (N=92). In Experiment 2 a simulator group (N=99) and a control group (N=81) were used. In both experiments, nation military service conscripts were used. The length of simulator-based training was changed. In Experiment 1 combatants received two two-week simulator-based combat training sessions. In Experiment 2 combatants received two four-week simulator-based combat training sessions. The control groups did not receive any simulator-based combat training. The Fig. 1. Survival rate on a combat track in Experiment 1. measurements were made three times (week 9, 17 and 21) during the 6-month national service period on a combat track.

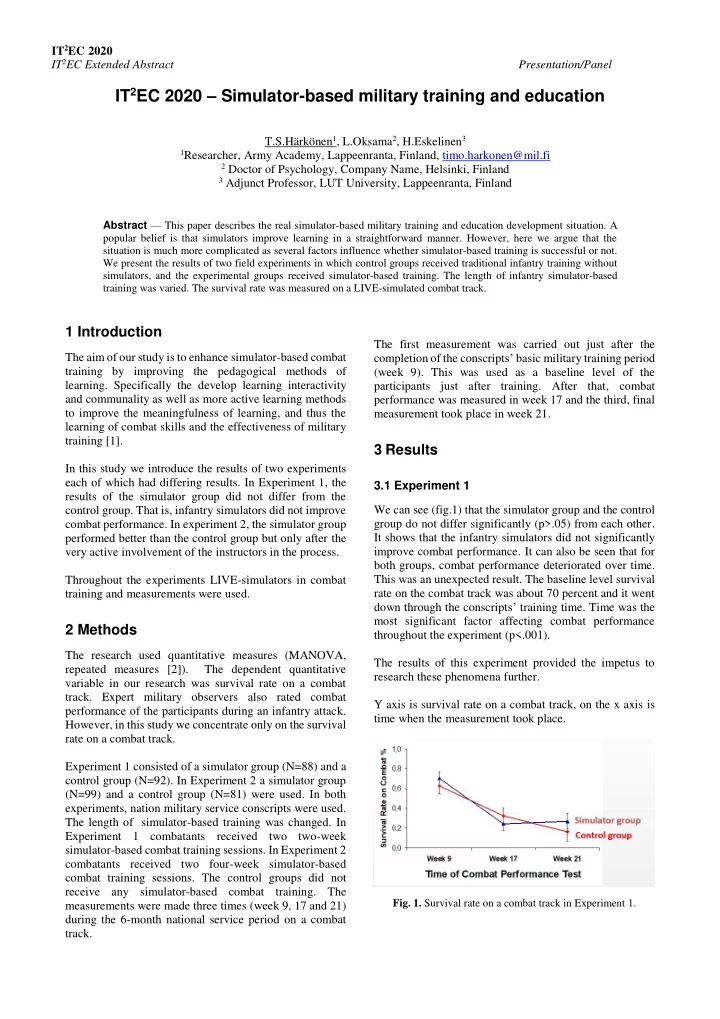

IT 2 EC 2020 IT 2 EC Extended Abstract Presentation/Panel 3.2 Experiment 2 One year after we performed Experiment 2. This time both the test time and simulator-based training and interaction were significant factors affecting the results. The simulator group performed better than the control group. In addition, combat performance improved throughout the duration of the experiment. However, there is a significant statistical interaction between the test time and simulator-based training which means that groups behaved differently. From the Week 9 measurement one can see that results were much lower than in Experiment 1. A part of the Fig. 3. Important elements of effective simulator training [4,5]. explanation would be that the conscripts had received 25 percent less combat training than conscripts in experiment 1. 5 Future Work After week 17 instructors were asked to provide more intensive teaching as well as timely and better feedback. Along with this study the observers used the combat video This influenced the performance between weeks 17 and camera, which was fastened to their helmets. After that, the 21. conscripts were interviewed and a retrospective video analysis was conducted. We gathered a lot of quantitative This huge improvement must be an effect of some and qualitative data about survival rates, conscript interplay between three factors: instructors, simulators and movement, communication, situation awareness and the the conscripts. use of assault rifles. We are currently researching education and training with small arms indoor simulators. 6 Conclusions This study was carried out in order to answer questions regarding appropriate simulator-based military education and training effectivity. In real life, one can learn a great deal just from the experience itself, without receiving feedback. However, in simulator-based training, specific Fig. 2. Survival rate on a combat track in Experiment 2. feedback is required to maximize learning. Military instructors are used to giving feedback for conscripts. In the simulator-based combat situations an instructor must 4 Lessons Learned give real time guidance and feedback to the conscripts. The timely provision of feedback by the instructor has very We posit that there are several factors that influence the transfer of learning, not just amount of simulator-based important role in simulator-based military training. We argue that without well-planned and executed feedback the training. In a simulator-based military training context there are three components available: combatant simulator-based military training is not effective at all. (conscript), instructor and simulator. All those components have a fundamental role in training. We argue that we need Acknowledgements active involvement of all these central factors in the learning process. We would like to thank Marko Vulli, Kari Papinniemi, Additionally, it should be remembered that a combatant Mika Karvonen, Marko Räsänen for their contribution to needs good motivation, good learning skills and good this study. attitude in order to be effective in training [3]. These same factors also apply to the instructor. He or she needs good References motivation, good teaching skills and good attitude that he or she can be effective teacher. The third component is the [1] Lindblom-Ylänne, S. & Nevgi, A. 2004. Oppimisen simulator. The simulator should fulfil the requirements arviointi – laadukkaan opetuksen perusta. In: S. made for it. It has to be reliable and its functionality has to Lindblom-Ylänne, A. Nevgi (Ed.) Yliopisto- ja be good and appropriate.

IT 2 EC 2020 IT 2 EC Extended Abstract Presentation/Panel korkeakouluopettajan käsikirja. Helsinki: Werner Söderstöm Osakeyhtiö, Pp. 253 – 268. [2] Nummenmaa, L. 2009. Tilastolliset menetelmät. Tammi. Helsinki. [3] Vincenzi, D. (Ed.), Wise, J. (Ed.), Mouloua, M. (Ed.) & Hancock, P. (Ed.). 2009. Human Factors in Simulation and Training. CRC Press. Boca Raton, London, New York. [4] Flexman, R. & Stark, E. 1987. Training Simulators. In: Salvendy, G. (Ed.) Handbook of Human Factors (Pp. 1012-1038). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [5] Roscoe, S., Jensen, N.& Gawron, V. 1980. Introduction to Training Systems. In: Roscoe, S. (Ed.) Aviation Psychology. Iowa: Iowa State University Press, Pp. 173-181. Author/Speaker Biographies Timo Härkönen is Researcher at Simulator Centre of Excellence in Finnish Army. He is post graduate student in University of Eastern Finland. Since 2010 he is active in the simulator-based training and education research, eager to improve it by enhanced design and measurements. Lauri Oksama is… Harri Eskelinen is… Lt. Col. Antti Pyykönen is Chief of Simulator Centre of Excellence in the Finnish Army. Since graduating from General Staff Officer Course (2002) he has been serving in research and development positions being Chief of Research and Development Department of Finnish Army for seven years, head of several materiel programs for four years and Army Academy Chief of Training for two years. In his current position he is responsible for the Finnish Army's simulator-based training development and annual planning for the use of the Finnish Army´s simulators.

Recommend

More recommend