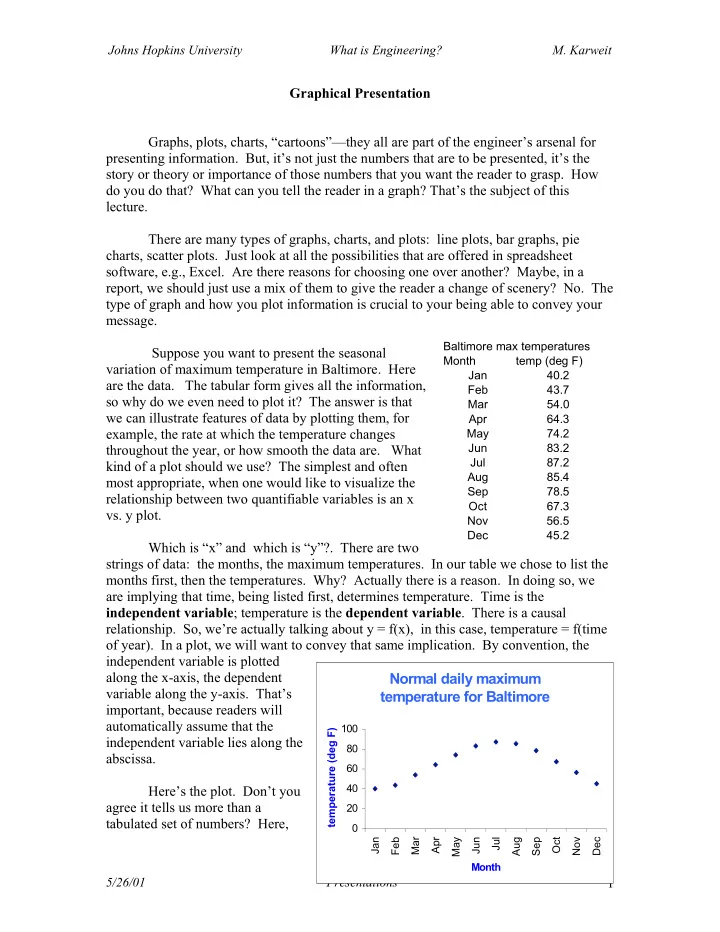

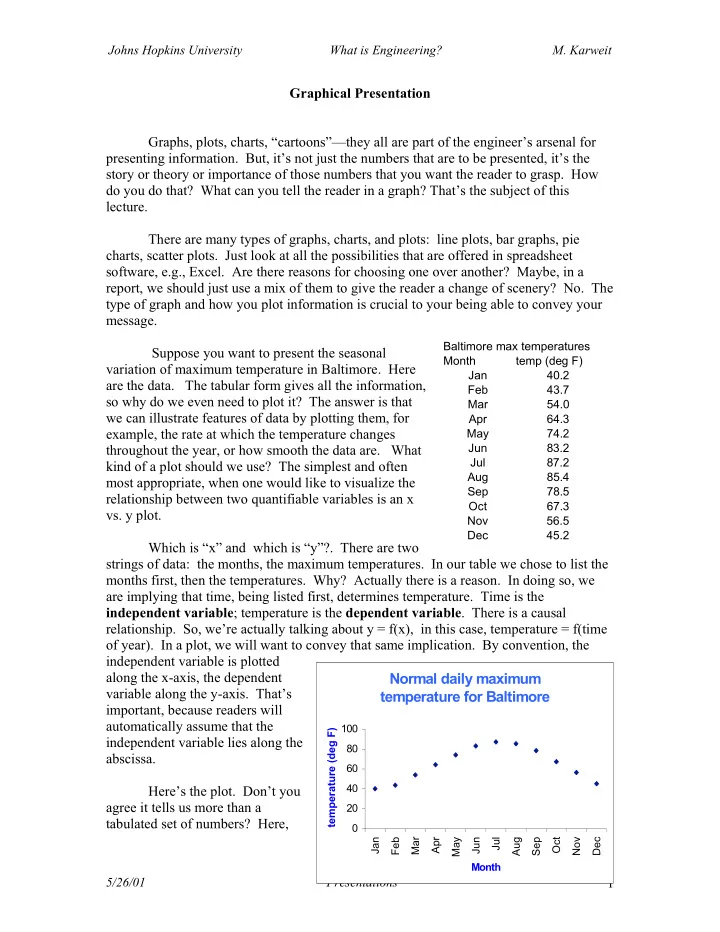

Johns Hopkins University What is Engineering? M. Karweit Graphical Presentation Graphs, plots, charts, “cartoons”—they all are part of the engineer’s arsenal for presenting information. But, it’s not just the numbers that are to be presented, it’s the story or theory or importance of those numbers that you want the reader to grasp. How do you do that? What can you tell the reader in a graph? That’s the subject of this lecture. There are many types of graphs, charts, and plots: line plots, bar graphs, pie charts, scatter plots. Just look at all the possibilities that are offered in spreadsheet software, e.g., Excel. Are there reasons for choosing one over another? Maybe, in a report, we should just use a mix of them to give the reader a change of scenery? No. The type of graph and how you plot information is crucial to your being able to convey your message. Baltimore max temperatures Suppose you want to present the seasonal Month temp (deg F) variation of maximum temperature in Baltimore. Here Jan 40.2 are the data. The tabular form gives all the information, Feb 43.7 so why do we even need to plot it? The answer is that Mar 54.0 we can illustrate features of data by plotting them, for Apr 64.3 example, the rate at which the temperature changes May 74.2 throughout the year, or how smooth the data are. What Jun 83.2 Jul 87.2 kind of a plot should we use? The simplest and often Aug 85.4 most appropriate, when one would like to visualize the Sep 78.5 relationship between two quantifiable variables is an x Oct 67.3 vs. y plot. Nov 56.5 Dec 45.2 Which is “x” and which is “y”?. There are two strings of data: the months, the maximum temperatures. In our table we chose to list the months first, then the temperatures. Why? Actually there is a reason. In doing so, we are implying that time, being listed first, determines temperature. Time is the independent variable ; temperature is the dependent variable . There is a causal relationship. So, we’re actually talking about y = f(x), in this case, temperature = f(time of year). In a plot, we will want to convey that same implication. By convention, the independent variable is plotted along the x-axis, the dependent Normal daily maximum variable along the y-axis. That’s temperature for Baltimore important, because readers will automatically assume that the 100 temperature (deg F) independent variable lies along the 80 abscissa. 60 40 Here’s the plot. Don’t you agree it tells us more than a 20 tabulated set of numbers? Here, 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Month 5/26/01 Presentations 1

Johns Hopkins University What is Engineering? M. Karweit you can see how the temperature changes month-by-month. It changes most rapidly during the spring and fall—an observation easy to make from a plot; hard to make from a tabulation of values. We can also visualize the smooth transition from one month to the next. In fact, we might be tempted to draw line segments between the data points. But that would be wrong. It is almost never appropriate to connect data points by lines (in spite of the fact that Excel offers a half-dozen plot styles that do so.) The reason it is wrong to put lines between the points is that, in doing so, you are suggesting that along the line is where other data would fall. You almost never know where other data will fall. The only time it’s appropriate to draw a curve or line is when it represents a theory or analytic function. Then the viewer can judge for himself whether the data fit the theory. Plots, graphs, and charts should always be fully annotated. That is, they should tell the whole story all by themselves. There should be no need for a reader to pore over the text to discover what the plot is about. Yes, it’s OK to elaborate further about the data in the text. But the plot with it’s figure caption should stand alone. Graphs need legends, axis descriptions, unit designations, titles. What else should we pay attention to in a simple plot? Scaling is one. We probably don’t have to discuss why it would be inappropriate to scale the y-axis from 0 to 1000 degrees. But why have we chosen a range of 0 to 100? We might have chosen a y- scaling of 40 degrees to 90 degrees. That would have certainly contained the data. By scaling it from 0 to 100 degrees, we offer the viewer an increased sense of the temperature. Maximum temperatures in inhabitable areas lie roughly between 0 and 100. So by choosing 0 to 100, we present not only Baltimore’s temperature range, but also where that range fits with respect to other inhabitable areas. It’s a subtle way of conveying a little more information. What if one of the variables isn’t quantifiable? That is suppose you want to present graphically “days to maturity” for growing a variety of vegetables. “days to maturity” is quantifiable. Type of vegetable is not. Here, a bar chart is appropriate. In a bar chart one axis suggests quantity, the other does not. Here’s a hypothetical Product satisfaction example of product satisfaction vs. brand. And 85 with this example, we also illustrate the importance of % satisfaction scaling. This chart might appear as a magazine 80 advertisement for Our Brand. First, notice that the brands could have been 75 Brand C placed in any order and in any Our Brand Brand B position horizontally, because Brands 5/26/01 Presentations 2

Johns Hopkins University What is Engineering? M. Karweit in bar charts, position does not necessarily connote value as in the case of x vs. y plots. If “brand” were quantifiable, for example, by including the cost for the product, then position could be used to emphasize that trait. But the bar chart style could still be used for impact. Now let’s turn our attention to the scaling of the bars. Here, “creative” scaling is used in an attempt to convince the consumer that Our Brand is far superior to others. At first glance, Our Brand does seem so much better than the others. Look how much higher the bar is! Only when one scrutinizes the scale does one realize that there is almost no difference between the brands. In fact, the error in estimating product satisfaction could very well be greater than the entire range of the graph. The graph is not lying, but its scaling attempts to mislead. This is the venue of marketing, not engineering. Be careful with your scaling. What about information that always adds up to one, or 100%?—like How your tax dollars were spent, Proportions of ethnicities in the U.S., Distribution of engineering students by field of study. An excellent way to give a visual impression of percentages is with a pie chart; one total “pie” equals 100%. Here’s one for the distribution of full- time engineering graduate students in 1997. Distribution of full-time graduate students in engineering, 1997. (n=65594) Aerospace Other 4% Chemical 12% Materials 9% 6% Civil Mechanical 17% 16% Industrial Electrical 8% 28% What could be visually clearer? In one glance, the viewer sees the overall picture. There’s a lot of electrical engineering students; not so many aerospace students. And, with the notation n=65594, the number of students in each discipline can be determined. These first few graphs have been simple: pick the right type; plot the data as is. But, plotting the data “as is” does not always display what you’d like to focus on. Consider the following: you are measuring the Euler buckling load of aluminum rod— the compressive load at which the rod just begins to bend. You suspect that the buckling load F is related to rod length L by a power law F(L) ∝ L n . You’d like to see if that’s 5/26/01 Presentations 3

Recommend

More recommend