Emotive motion: Analysis of Expressive Timing and Body Movement in - PDF document

Emotive motion: Analysis of Expressive Timing and Body Movement in the Performance of an Expert Violinist Position Paths: Figure 1 demonstrates the position path of the center of pressure for each of the eight performances. This can be thought

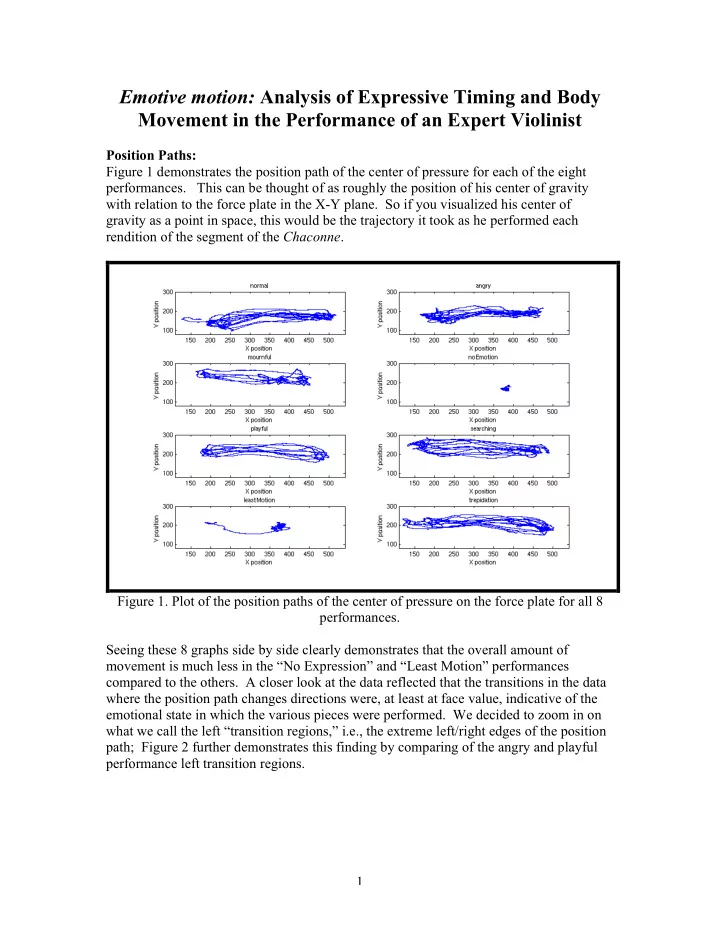

Emotive motion: Analysis of Expressive Timing and Body Movement in the Performance of an Expert Violinist Position Paths: Figure 1 demonstrates the position path of the center of pressure for each of the eight performances. This can be thought of as roughly the position of his center of gravity with relation to the force plate in the X-Y plane. So if you visualized his center of gravity as a point in space, this would be the trajectory it took as he performed each rendition of the segment of the Chaconne . Figure 1. Plot of the position paths of the center of pressure on the force plate for all 8 performances. Seeing these 8 graphs side by side clearly demonstrates that the overall amount of movement is much less in the “No Expression” and “Least Motion” performances compared to the others. A closer look at the data reflected that the transitions in the data where the position path changes directions were, at least at face value, indicative of the emotional state in which the various pieces were performed. We decided to zoom in on what we call the left “transition regions,” i.e., the extreme left/right edges of the position path; Figure 2 further demonstrates this finding by comparing of the angry and playful performance left transition regions. 1

Figure 2. Plot of the left “transition region” of the position paths of the center of pressure of the angry and playful performances Figure 2 clearly demonstrates the jaggedness of the angry performance “transition region” versus the rounded appearance of the playful performance. This finding led us to consider a series of ways to quantify this easily visualized qualitative difference. In order to quantify the jaggedness of the transition region, we took the Cartesian first derivative of the center of pressure X position and Y position data with respect to time. We converted these values into polar coordinates to produce the angle of the direction of the velocity vector of the position path. We then took the first order derivative of that angle in order to quantify the rate in which that value was changing. Figure 3 is the plot of the jaggedness of the eight performances. While there are what appear to be strong peaks in the data, we were unable to derive conclusive meaning for these graphs. 2

Figure 3. Plot of the first derivative of the angle of the velocity vector of the position path data with respect to time for each of the 8 performances. Tempo Curves: The musical “tempo” is the rate at which beats occur, generally in units of beats per minute. Modulation of tempo, i.e., speeding up and slowing down, is an essential element of Mr. Shiffman’s (or any other skilled Western classical musician’s) expressiveness. John painstakingly marked the time at which each of the 17 measures and 171 notes began in each of the 8 performances. From these note onset times it is simple to compute what might be called the “per-note instantaneous tempo”: 1) take each inter-onset interval (time between successive onsets) 2) take the reciprocal 3) scale by each note's duration in the score (to account for the fact that you expect eighth notes to be twice as long as sixteenth notes) 4) scale by the right constant to make the units be beats per minute. We used this method (on a per-bar basis) to produce Figure 4. 3

Figure 4: Comparison of per-bar tempo for all 8 performances. Note that higher-tempo performances have the same rate. (The integral of each tempo function is 48 beats, the duration of the excerpt.) We believe that the per-note (or per-beat) tempo curve is too jagged, and does not match actual perception of tempo. In other words, if one note’s duration is smaller than the nearby notes, we don’t perceive that the tempo sped up just for that one note and then slowed down again, but rather that the subsequent note slightly anticipated the beat. Therefore we smoothed the tempo curve 1 with a triangular kernel. For example, a length- three kernel would be [1/2, 1, 1/2], and smoothing with this kernel would mean output (n) = 0.5* input (n-1) + 1.0* input (n) + 0.5* input (n+1) for each position n. 2 The tempo curve predicts the time at which each note should be occur. Obviously, the more one changes the tempo curve, the more these predictions will differ from the true event onset times. We refer to these differences as the per-note deviations ; our convention is that a positive deviation indicates a note that comes after the time predicted by the tempo curve, whereas a negative deviation indicates a note that comes earlier than expected. Figure 5 shows the result of successively smoothing the tempo curve as well as the resulting deviations. 1 In fact, to avoid accumulating note offset times, we actually smoothed the integral of the tempo curve, sometimes known as a “time map,” which simply marks (fractional) number of beats elapsed as a function of time in each performance. The “smoothed tempo curve” is therefore in fact the derivative of the smoothed integral of the tempo curve. Please ignore this detail unless you’re interested in such matters. 2 Another tricky detail you’re probably better off ignoring: near the beginning and end of the original tempo curve, we shorten the window to make sure we don’t run off the edge. 4

Figure 5: The left column is tempo curves; each stem plot in the right column shows the per-note deviations computed from the corresponding tempo curve. 5

Temporal Correspondence: Correlation Analysis Our hypothesis was that elements of expressive timing would be manifested in the physical motion of Mr. Shiffman’s body. To test this, we methodically correlated all motion data (as functions of time) with the tempo curves and per-note deviation values (also functions of time) for the corresponding performances. 3 This section tabulates the results with the highest correlation coefficient (rho). In all cases, since the sampling rate is a 240 Hz and the duration of each performance is at least 30 seconds, there was an abundance of data points, so the P-value was infinitesimally small (i.e., 10^-30 or less). Measure 1 Rho Value Violin 2 (Y) -0.3809 L 5 th Toe (Y) -0.34825 Top Head (Y) -0.34798 L Acromion (Y) -0.34739 Violin 2 (Z) -0.33947 R Thigh (Y) +0.33541 R DIP 2 (X) -0.31052 L Toe (Y) -0.32944 Violin 3 (Y) -0.30104 L heel (X) 0.3004 R Med Scapula (dy/dt) -0.26621 L Med Scapula (dy/dt) -0.25094 R Clavicle (dy/dt) -0.24437 L Knee 3D Speed +0.2887 L Shank 3D Speed +0.27324 Forceplate Position -0.20498 (FP) X No Emotion FP X -0.44318 No Emotion FP Y +0.21664 Playful FP X +0.311 Playful FP Y -0.29882 Least Motion FP Y +0.27981 Least Motion FP X +0.23073 Table 1. Correlation of various markers and force plate data to tempo. Rho values indicate the degree of correlation of the data set to the tempo curve. A rho value of 1 would indicate complete correlation (i.e., that the given motion parameter is always exactly a scalar times the tempo curve) while a rho value of 0 implies no correlation at all (i.e., that the given motion parameter is completely statistically independent from the tempo curve). 3 In fact, we used a few different smoothness values (i.e., smoothing kernel lengths); we will ignore this detail. 6

As demonstrated in Table 1, it was interesting to find that the highest correlations of Speed with tempo were in the knee and shank. Whereas the high correlations of position with tempo occurred literally from head to toe. The high correlations of the per- dimension velocity with tempo were all relative to the Y position of the scapula and clavicle. This indicates that superior/inferior motion of the shoulder highly correlates to the tempo in this performance. The 3D acceleration of all markers had at most a rho value of .07 with any of the timing parameters. This indicates that acceleration has almost no relation to tempo. Due to our overambitious application of markers during data collection, it proved to be prohibitively time consuming to clean the motion capture data. Therefore all of the above correlative analysis describes only the “Normal” performance of the piece. However, we did further correlative investigation using the force plate data for the remaining seven performances. Each of the different performances had widely differing degrees of correlation between the force plate data and timing parameters, ranging from the “Angry” performance, whose highest correlation was a rho value of 0.07 to the “No Emotion” performance, whose highest correlation was a rho value -0.44. In other words, for certain performances he physically manifested the tempo in the shifting of his body weight, but in others, not. This finding is doubly remarkable, because in the “No Emotion” case he wasn’t visibly shifting his weight back and forth, and as Figure 1 demonstrates the amplitude was low and there didn’t seem to be any correlation between his movements and the incidence of the bar lines. 7

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.