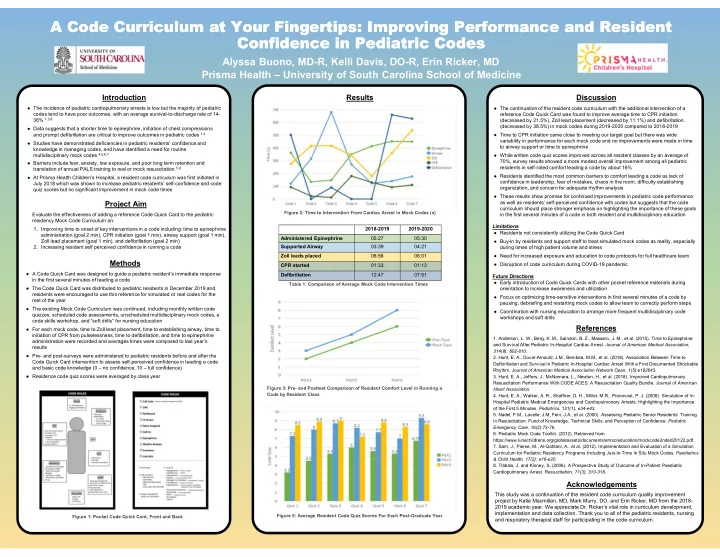

A Code Curriculum at Your Fingertips: Improving Performance and Resident A Code Curriculum at Your Fingertips: Improving Performance and Resident Confidence in Pediatric Codes Confidence in Pediatric Codes Alyssa Buono, MD-R, Kelli Davis, DO-R, Erin Ricker, MD Prisma Health – University of South Carolina School of Medicine Introduction Results Discussion ● The incidence of pediatric cardiopulmonary arrests is low but the majority of pediatric ● The continuation of the resident code curriculum with the additional intervention of a codes tend to have poor outcomes, with an average survival-to-discharge rate of 14- reference Code Quick Card was found to improve average time to CPR initiation 36% 1,3,8 (decreased by 21.5%), Zoll lead placement (decreased by 11.1%) and defibrillation. (decreased by 38.5%) in mock codes during 2019-2020 compared to 2018-2019 ● Data suggests that a shorter time to epinephrine, initiation of chest compressions and prompt defibrillation are critical to improve outcomes in pediatric codes 1,2 ● Time to CPR initiation came close to meeting our target goal but there was wide variability in performance for each mock code and no improvements were made in time ● Studies have demonstrated deficiencies in pediatric residents’ confidence and to airway support or time to epinephrine knowledge in managing codes, and have identified a need for routine multidisciplinary mock codes 4,5,6,7 ● While written code quiz scores improved across all resident classes by an average of 70%, survey results showed a more modest overall improvement among all pediatric ● Barriers include fear, anxiety, low exposure, and poor long term retention and residents in self-rated comfort leading a code by about 16% translation of annual PALS training to real or mock resuscitation 5,6 ● Residents identified the most common barriers to comfort leading a code as lack of ● At Prisma Health Children’s Hospital, a resident code curriculum was first initiated in confidence in leadership, fear of mistakes, chaos in the room, difficulty establishing July 2018 which was shown to increase pediatric residents’ self-confidence and code organization, and concern for adequate rhythm analysis quiz scores but no significant improvement in mock code times ● These results show promise for continued improvements in pediatric code performance Project Aim as well as residents’ self-perceived confidence with codes but suggests that the code curriculum should place stronger emphasis on highlighting the importance of these goals Figure 2: Time to Intervention From Cardiac Arrest in Mock Codes (s) Evaluate the effectiveness of adding a reference Code Quick Card to the pediatric in the first several minutes of a code in both resident and multidisciplinary education residency Mock Code Curriculum on: Limitations 1. Improving time to onset of key interventions in a code including: time to epinephrine 2018-2019 2019-2020 ● Residents not consistently utilizing the Code Quick Card administration (goal 2 min), CPR initiation (goal 1 min), airway support (goal 1 min), Administered Epinephrine 05:27 05:30 Zoll lead placement (goal 1 min), and defibrillation (goal 2 min) ● Buy-in by residents and support staff to treat simulated mock codes as reality, especially Supported Airway 03:39 04:21 2. Increasing resident self perceived confidence in running a code during times of high patient volume and stress Zoll leads placed 06:56 06:01 ● Need for increased exposure and education to code protocols for full healthcare team Methods ● Disruption of code curriculum during COVID-19 pandemic CPR started 01:33 01:13 ● A Code Quick Card was designed to guide a pediatric resident’s immediate response Defibrillation 12:47 07:51 Future Directions in the first several minutes of leading a code ● Early introduction of Code Quick Cards with other pocket reference materials during Table 1: Comparison of Average Mock Code Intervention Times ● The Code Quick Card was distributed to pediatric residents in December 2019 and orientation to increase awareness and utilization residents were encouraged to use this reference for simulated or real codes for the ● Focus on optimizing time-sensitive interventions in first several minutes of a code by rest of the year pausing, debriefing and restarting mock codes to allow team to correctly perform steps ● The existing Mock Code Curriculum was continued, including monthly written code ● Coordination with nursing education to arrange more frequent multidisciplinary code quizzes, scheduled code assessments, unscheduled multidisciplinary mock codes, a workshops and soft drills code skills workshop, and “soft drills” for nursing education References ● For each mock code, time to Zoll lead placement, time to establishing airway, time to initiation of CPR from pulselessness, time to defibrillation, and time to epinephrine 1. Anderson, L. W., Berg, K. M., Saindon, B. Z., Massaro, J. M., et al. (2015). Time to Epinephrine administration were recorded and averages times were compared to last year’s and Survival After Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Journal of American Medical Association, results 314(8), 802-810. ● Pre- and post-surveys were administered to pediatric residents before and after the 2. Hunt, E. A., Duval-Arnould, J.M., Bembea, M.M., et al. (2018). Association Between Time to Code Quick Card intervention to assess self-perceived confidence in leading a code Defibrillation and Survival in Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest With a First Documented Shockable and basic code knowledge (0 – no confidence, 10 – full confidence) Rhythm. Journal of American Medical Association Network Open, 1(5):e182643. ● Residence code quiz scores were averaged by class year 3. Hunt, E. A., Jeffers, J., McNamara, L., Newton, H., et al. (2018). Improved Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Performance With CODE ACES: A Resuscitation Quality Bundle. Journal of American Figure 3: Pre- and Posttest Comparison of Resident Comfort Level in Running a Heart Association. Code by Resident Class 4. Hunt, E. A., Walker, A. R., Shaffner, D. H., Miller, M.R., Pronovost, P. J. (2008). Simulation of In- Hospital Pediatric Medical Emergencies and Cardiopulmonary Arrests: Highlighting the Importance of the First 5 Minutes. Pediatrics, 121(1), e34-e43. 5. Nadel, F.M., Lavelle, J.M, Fein, J.A., et al. (2000). Assessing Pediatric Senior Residents’ Training in Resuscitation: Fund of Knowledge, Technical Skills, and Perception of Confidence. Pediatric Emergency Care , 16(2):73-76. 6. Pediatric Mock Code Toolkit. (2012). Retrieved from https://www.luriechildrens.org/globalassets/documents/emsc/education/mockcode2nded20122.pdf. 7. Sam, J., Pierse, M., Al-Qahtani, A., et al. (2012). Implementation and Evaluation of a Simulation Curriculum for Pediatric Residency Programs Including Just-In-Time In Situ Mock Codes. Paediatrics & Child Health, 17(2): e16-e20. 8. Tibbals, J. and Kinney, S. (2006). A Prospective Study of Outcome of In-Patient Paediatric Cardiopulmonary Arrest. Resuscitation , 71(3), 310-318. Acknowledgements This study was a continuation of the resident code curriculum quality improvement project by Katie Macmillan, MD, Mark Murry, DO, and Erin Ricker, MD from the 2018- 2019 academic year. We appreciate Dr. Ricker’s vital role in curriculum development, implementation and data collection. Thank you to all of the pediatric residents, nursing Figure 5: Average Resident Code Quiz Scores For Each Post-Graduate Year Figure 1: Pocket Code Quick Card, Front and Back and respiratory therapist staff for participating in the code curriculum.

Recommend

More recommend