Topics in the syntax of ellipsis Patrick D. Elliott and Andrew - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Topics in the syntax of ellipsis Patrick D. Elliott and Andrew Murphy 25.06.2018 1 Some preliminaries You can fjnd the course page here: Slides for the fjrst class: Well dynamically-update the course page with slides and

Strict syntactic isomorphism • We can take as a null hypothesis the following identity relation, since it’s the most restrictive. (28) Strict syntactic isomorphims The sluice and its antecedent are identical ifg the sluice and its antecedent are isomorphic syntactic structures involving identical phrase markers. 26

Strict syntactic isomorphism ii • Strict syntactic isomorphism already has issues with even the most basic cases: (29) Fraser made out with some guy, • If we adopt a trace-theoretic approach to movement, we can resolve this apparent mismatch by QR-ing some guy out of the antecedent clause, leaving behind a trace. 27 but I don’t remember who 𝑦 Fraser made out with 𝑢 𝑦 .

Strict syntactic isomorphism iii DP 𝑦 𝑢 𝑦 with PP made out V VP T T’ Fraser DP TP who TP TP 𝑢 𝑦 with PP made out V VP T T’ Fraser DP TP some guy DP 𝑦 28

Strict syntactic isomorphism iv • If we adopt a copy-theoretic approach to movement however (more in vogue in current minimalism), we still have a problem. EC: ⟨ who ⟩ Fraser made out with ⟨ who ⟩ 29 (30) AC: ⟨ some guy ⟩ Fraser made out with ⟨ some guy ⟩

Strict syntactic isomorphism v • Here’s a sketch of an analysis consistent with strict syntactic isomorphism and the copy theory of movement. • wh-expressions and indefjnites are in fact identical in the narrow syntax. Let’s call them indeterminates . • Indeterminates that move to the spec of a quantifjcation-related head in the left periphery - let’s call it A - are spelled out as indefjnites at PF. • Indeterminates that move to the spec of the interrogative complementiser are spelled out as wh -expressions at PF. • According to a standard semantics for wh -question, wh- expressions are contribute existential quantifjcation (Karttunen 1977), so this poses no problems at LF. 30

Strict syntactic isomorphism vi (4) ‘tell me who ran‘ tell. oshiete. ] ] ran-KA hashitta-ka who-nom dare-ga [ CP [ CP ‘Someone ran’ • Support for this kind of analysis comes from languages such as ran. hashitta. -nom -ga ] ] who-KA dare-ka [ DP [ DP (3) Japanese , in which we observe indeterminates in the morphosyntax. 31

Strict syntactic isomorphism vii • I don’t want to endorse this analysis, the point here is that strict syntactic isomorphism forces us to make non-trivial decisions about the narrow syntax. • In that sense, it is mor restrictive than other identity conditions, but the risk is that the analyses end up looking somewhat ad hoc . 32

Strict syntactic isomorphism viii • In fact, I think this kind of reasoning is bound to run into an insuperable obstacle sooner or later. • Consider, e.g., the following contrast sluicing example: (31) I know ⟨ which professor ⟩ Elin danced with ⟨ which professor ⟩ . • Under a copy-theoretic approach to ellipsis, it’s extremely diffjcult to explain why this kind of lexical mismatch is tolerated. • A trace-theoretic approach to movement seems to fare better here, but we have independent reasons to want to maintain a copy-theoretic analysis (binding reconstruction, theoretical parsimony, etc.). 33 I wonder ⟨ which student ⟩ Elin danced with ⟨ which student ⟩

Strict syntactic isomorphism ix • There are even more straightforward challenges for strict syntactic isomorphism (Merchant 2001 is the locus classicus for this). • There are perhaps involved stories one could tell in order to resolve this apparent mismatch in the syntax, but it’s defjnitely not going to be easy. 34 (32) I’ll fjx the car, if you tell me… …how to fjx the car 𝑢 . ✓ …how I’ll fjx the car 𝑢 . ✗ (33) Nathan has a new boyfriend, but I don’t know… … who he is 𝑢 ✓ …who Nathan has 𝑢 ✗

Islands • It’s not usually framed this way, but the primary argument against strict syntactic isomorphism comes from islands . • A little background fjrst: • One of the most important discoveries of generative syntax is that wh- and other varities of overt movement are systematically blocked out of certain environments, which we call islands (Ross 1967). N.b. that I’m using movement here as a placeholder for whatever theory encodes the dependency between fjllers and gaps . Even if your favourite theory of syntax doesn’t have movement , it still needs a theory of islands otherwise it’s dead in the water. 35 (34) * [ …XP 𝑗 … [ island … 𝑢 𝑗 … ] … ]

Sluicing and wh- movement • There independent evidence that sluicing involves genuine wh- movement out of elided syntactic structure, schematised below: • For example, sluicing tracks independent restrictions on pied-piping in wh -movement: (36) c. *I don’t know pictures of whom you found 𝑢 DP on the internet. (37) John found pictures of someone on the internet… a. …but I don’t know whom you found pictures of 𝑢 on the internet. 36 (35) Elin danced with someone, but I’m not sure who 𝑗 Elin danced with 𝑢 𝑗 a. I don’t know whom you found [ DP pictures of 𝑢 DP] on the internet. b. ?I don’t know of whom you found [ DP pictures 𝑢 PP] on the internet. b. ?…but I don’t know of whom you found pictures 𝑢 on the internet. c. *…but I don’t know pictures of whom you found 𝑢 .

Sluicing and wh- movement ii • If sluicing involves a movement + deletion derivation, then we make a straightforward prediction. • The following confjguration should be ungrammatical: 37 (38) * [ antecedent … [ island … correlate … ] … ] … [ sluice … remnant 𝑗 … ... [ island ... 𝑢 𝑗 ... ] ]

wh -islands (39) Wh-island Condition No wh-phrase may cross a CP with a [+wh] element in [Spec, CP] or C 0 (Chomsky 1973). (41) a. ??Whose car were you wondering how to fjx 𝑢 whose car ? b. ?*Whose car were you wondering how you should fjx 𝑢 whose car ? 38 (40) a. When did the boy say 𝑢 when [that he had hurt himself]? b. When did the boy say 𝑢 when [how he had hurt himself 𝑢 how ]? c. When did the boy say [that he had hurt himself 𝑢 when ]? d. *When did the boy say [how he had hurt himself 𝑢 how 𝑢 when ]?

wh -islands ii • Not all wh-expressions are afgected equally by wh-islands. Movement of a so-called d-linked wh-expression, such as which boy , is more acceptable (see Pesetsky 1982). (42) ??Which boy are you trying to decide whether to kiss 𝑢 which boy ? 39

The CNPC (43) The Complex NP Constraint (CNPC) No element contained in a sentence dominated by a noun phrase […] may be moved out of that noun phrase. (Ross 1967) • Relative Clause • Nominal Complement 40 • In more contemporary terms: [ DP … [ CP … ]] is an island. (44) You know [ DP a man [ CP who photographed the pyramids]]. (45) *What do you know [ DP a man [ CP who photographed 𝑢 ]]? (46) You believed [ DP the claim [ CP that we had seen Steely Dan]]. (47) Which band did you believe [ DP [ CP the claim that we had seen 𝑢 ]]?

The CNPC ii • Compare the examples to simple extraction from DPs: • Extraction from DPs can be allowed, as long as the DP is not defjnite/specifjc 41 (48) Which band did you write [ DP an article about 𝑢 ]? (49) ??Which band did you write [ DP that article about 𝑢 ]? (50) *Which band did you read [ DP Joe’s article about 𝑢 ]?

The subject condition (51) The subject condition No element may be moved out of a subject. (Ross 1967,Chomsky 1973) (52) DP obj. extraction (53) DP subj. extraction (54) CP obj. extraction (55) CP subj. extraction 42 Which actor did Van Gogh paint [ DP a close friend of 𝑢 ]? *Which actor did [ DP a close friend of 𝑢 ] paint van Gogh? What does Frank believe [ CP that he stole 𝑢 from the library]? *What is [ CP that Frank stole 𝑢 from the library] widely believed?

The subject condition ii • The Subject Condition is sometimes subsumed under the Freezing Principle (Ross 1967), which prohibits movement from a moved constituent, on the assumption that subjects undergo obligatory movement from a VP internal position. Under this analysis, subjects are often grouped together with topics as Derived Position Islands : (56) Topic Island b. *Which communist did she say that [a book about 𝑢 ], she refused to read. 43 a. She said that [ DP a book about Trotsky], she refused to read 𝑢 .

The CSC (57) The Co-ordinate Structure Constraint (CSC) In a coordinate structure, no conjunct may be moved, nor may any element contained in a conjunct be moved out of that conjunct. (58) Williams unifjed rule (Williams 1977) If a rule applies into a coordinate structure, then it must afgect all conjuncts of that structure. (59) I eat French fries with ketchup. (60) I eat French fries and ketchup. (61) I think Mary bought a book and Frank sold a CD. (62) *What do you think Mary bought a book and Frank sold 𝑢 ?. 44 What do you eat [ NP French fries [ PP with 𝑢 ]]? *What do you eat [ andP French fries and 𝑢 ]? *What do you think [ andP Mary bought 𝑢 and Frank sold a CD]. What do you think [ andP Mary bought 𝑢 and Frank sold 𝑢 ]?

The CSC ii • It has been noted that there are some apparently systematic exceptions to the CSC (see Kehler 2002 for a contemporary discussion). • When the two conjuncts stand in a particular kind of semantic relationship, extraction from one of the conjuncts may be possible: 45 (63) What did John [ andP go to the shops and buy 𝑢 ]? (64) How much can you [ andP drink 𝑢 and still stay sober]?

The LBC (65) The Left Branch Condition (LBC) Extraction of α is banned in the following confjguration, where X is any (Ross 1967,Corver 1990) 46 non-null material: [ DP α X ] (66) a. *Whose did you play [ DP 𝑢 favorite guitar]? b. * Whose friend’s did you play [ DP 𝑢 favorite guitar]? c. * Whose friend did you play [ DP 𝑢 ’s favorite guitar]? (67) a. *How did Mary marry [ DP a 𝑢 tall man]. b. *How tall did Mary marry [ DP a 𝑢 man].

The LBC ii • A process called pied-piping by Ross (named after the Pied Piper of Hamelin) rescues such sentences: (68) Whose favorite guitar did you play 𝑢 ? (69) Whose friend’s favorite guitar did you play 𝑢 ? (70) How tall a man did Mary marry? 47

The LBC and cross-linguistic variation How many (French) How many have you read 𝑢 books? books livres? of de read lu -you -tu have as Combien • Unlike most of the other island conditions we’ve looked at, the LBC is (6) (Russian) Which did you buy 𝑢 ? book.acc.fem knigu? bought.masc kupil you ty which.acc.fem Kakuyu (5) subject to substantial cross-linguistic variation. 48

Adjunct condition (71) The Adunct condition No element may be moved out of an adjunct. (72) a. John went home [after he had talked to Sally]. b. *Who did John go home [after he had talked to 𝑢 who]? (73) a. John is angry [because Mary bought a computer]. b. *What is John angry [because Mary bought 𝑢 what]? (74) a. Friederike listens to music [while she does her homework]. b. *What does Frierike listen to music [while she does 𝑢 what]? 49

Locality theory movement to the edge and the phrase being a complement (of a • Find out more about this in Andy’s class next week! proceed via the phase-edge. spelled-out over the course of the derivation. Movement may only identifjed as phase heads. The complement of a phase head is • Phase Theory (Chomsky 2001): particular heads (usually 𝑤 and C) are functional or lexical head). relations and must be unlocked by the twin mechanism of intermediate • Many attempts have been made to come up with a unifjed theory of • Barriers (Chomsky 1986): By default phrases are opaque to movement overwriting traces/returning to a lower cycle is disallowed. only the landing sites designated for X-movement along the path; • Subjacency/Strict Cycle (Chomsky 1973): X-movement lands in all and succeed. which seem semantic in nature, such an enterprise seems unlikely to locality - although note, on the basis of certain systematic exceptions 50

Islands and sluicing • If sluicing involves wh- movement out of silent (isomorphic) syntactic structure, we make a straightforward prediction: sluicing should exhibit sensitivity to island efgects. • In other words, the following confjguration should be ungrammatical: • Infamously, this prediction goes spectacularly wrong. 51 (75) * [ antecedent … [ island … correlate … ] … ] … [ sluice … remnant 𝑗 … ... [ island ... 𝑢 𝑗 ... ] ]

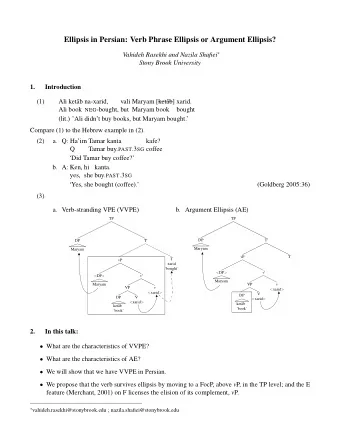

Sluicing and the CNPC (76) Complex NP Constraint (relative clause) but I don’t remember which Δ. b. *I don’t remember • Prediction: 52 a. They want to hire [ island someone who speaks a Balkan language], which (Balkan language) they want to hire [ island someone who speaks 𝑢 ]. which they want to hire [ island someone who speaks 𝑢 ] ✗

Sluicing and the LBC (77) Left-Branch Condition (attributive adjective case) a. She bought a big car, but I don’t know how big Δ. b. *I don’t know how big she bought [a 𝑢 car]. • Prediction: 53 how big she bought a 𝑢 car ✗

Sluicing and derived positon islands (78) Derived Position Island (subjects, topics) year — guess which Δ! this year. • Prediction: year 54 a. [ island A biography of one of the Marx brothers] is going to be published this b. *Guess which (Marx brother) [ island a biography of 𝑢 ] is going to be published which Marx brother [ island a biography of 𝑢 ] is going to be published this

Sluicing and the CSC • Coordinate Structure Constraint: (79) a. They persuaded Kennedy and some other Senator to jointly sponsor the legislation, but I can’t remember which one. b. *…but I can’t remember which one they persuaded [Kennedy and 𝑢 ] to jointly sponsor the legislation. • Prediction: (80) c. Bob ate dinner and saw a movie that night, but he didn’t say which movie. d. *…but he didn’t say which movie he ate dinner and [saw 𝑢 that night]. • Prediction: 55 which one they persuaded [ island Kennedy and 𝑢 ] to jointly sponsor the legislation ✗ which move he ate dinner and [ island saw 𝑢 that night] ✗

Sluicing and adjunct islands (81) a. Ben will be mad if Abby talks to one of the teachers, but she couldn’t remember which. b. * Ben will be mad if Abby talks to one of the teachers, but she couldn’t remember which (of the teachers) Ben will be mad [if she talks to 𝑢 ]. • Prediction: (82) a. Ben left the party because one of the guests insulted him, but he wouldn’t tell me which. b. *…but he wouldn’t tell me which (of the guests) Ben left the party [because 𝑢 insulted him]. • Prediction: 56 which he will be mad [ island if she talks to 𝑢 ] ✗ which he left the party [ island because 𝑢 insulted him] ✗

Sluicing and wh -islands certain problem], but she wouldn’t tell us which one Δ. • Prediction: 57 (83) a. Sandy was trying to work out [ island which students would be able to solve a b. *…but she wouldn’t tell us which one 𝑗 she was trying to work out [ island which students would be able to solve 𝑢 𝑗 ]. which one she was trying to work out [ island which students would be able to solve 𝑢 ] ✗

Summary • The hypothesis that sluicing involves wh -movement from a syntactically identical structure makes a major prediction: sluicing should be island sensitive. It follows that whenever the correlate is embedded in an island, the sluice must be ungrammatical. This is emphatically not the case, so something’s got to give. • In the literature, many simply took this to be a powerful argument that sluicing does not involve movement at all. This has been a popular approach in the literature. See e.g. Chung, Ladusaw & McCloskey (1995) for an approach which combines a structured ellipsis site with base-generation of the remnant in its surface position. • There is, however, good evidence from e.g. constraints on pied-piping and, as we will see later, preposition-stranding and case-matching. 58

The problem • We end up with a tension: • On the one hand, we have evidence that sluicing involves movement and silent syntactic structure . • On the other hand, evidence from islands seems to contradict this analysis. • However, the prediction that sluicing repairs island efgects relies on a crucial premise – the elided syntactic structure is syntactically isomorphic with the structure of the antecedent. 59

The proposed solution • The idea I’d like to explore here - originally developed by Merchant (2001) – is that sluicing does involve movement and deletion, but the elided structure can be distinct from the antecedent structure – our identity condition should allow for some syntactic deviation. • I’ll call this approach to islands under ellipsis island evasion , following Barros, Elliott & Thoms (2014). 60

The proposed soluton ii • Here’s an example of what I have in mind: • To get this idea ofg the ground, we’re going to need an identity condition that allows the syntax of the ellipsis site to deviate from the syntax of the antecedent. • In order to do this, we’re going to need a semantic identity condition. In the following slides, I’ll outline Merchant’s e-givenness condition. 61 (84) She bought a big car, but I don’t know how big [it 𝑦 was 𝑢 ]

e-GIVENness (85) Focus closure F-clo ( XP ) is the result of replacing F(ocus)-marked expressions in XP with variables , and existentially closing the result, modulo ∃ -type-shifting. (86) e-GIVENness XP 𝐵 , and… 62 A constituent XP 𝐹 counts as e-GIVEN ifg XP 𝐹 has a salient antecedent a. XP 𝐵 entails F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) . b. XP 𝐹 entails F-clo ( XP 𝐵 )

e-GIVENness for a basic case of sluicing • The antecedent has no focused material, so: F-clo ( XP A ) = ⟦ XP A ⟧ ∃𝑦[ hugged ( Elin , 𝑦)] • In the elided constituent, the trace of wh -movement, gets ∃− closed via ∃− type-shifting. It doesn’t contain any focused material so: F-clo ( XP E ) = ⟦ XP E ⟧ ∃𝑦[ hugged ( Elin , 𝑦)] 63 (87) [ antecedent Elin hugged someone], but I don’t know [ sluice who 𝑗 Elin hugged 𝑢 𝑗 ]. • Trivially, then XP 𝐵 entails F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) , and vice versa.

e-GIVENness and VP ellipsis • e-GIVENness isn’t just intended as a construction-specifjc condition imposed on sluicing, but rather as a general identity condition constraining ellipsis. • The antecedent and the ellipsis site are semantically, identical, so the ellipsis site trivially counts as e-GIVEN. 64 (88) Elin -ed [ antecedent stay out until 7 am], and Fraser did stay out until 7am too.

Contrast sluicing • Why did we make our semantic identity condition sensitive to focused material? • This is necessary in order to account for contrastive sluicing . • F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) = ∃𝑦[ dancedWith ( Elin , 𝑦)] • F-clo ( XP 𝐵 ) = ∃𝑦[ dancedWith ( Elin , 𝑦)] 65 (89) Elin danced with Fraser, but I don’t know who else Elin danced with 𝑢 .

Advantages - form mismatches • Vehicle change under VP ellipsis • F-clo ( XP 𝐵 ) = ∃𝑦[ admire (𝑦, Madison ) • F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) = ∃𝑦[ admire (𝑦, 1 )] through! 66 (90) Henning -s [ antecedent 𝑢 𝐼 admire Madison 1 ], a. …and she 1 said that Nathan does 𝑢 𝑂 admire her 1 too. b. *…and she 1 said that Nathan does admire Madison 𝑗 too. • In a context where 1 = Madison , bi-directional entailment goes

Semantic Identity and Island Evasion • As a proof of concept, let’s see how semantic identity, with a minor modifjcation, allows for the island evasion source we suggested for the putative LBC violation. (91) Andy has a huge suitcase, • F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) = ∃𝑒[𝜅𝑦[𝑦 a suitcase of Andy’s ] is huge d ] satisfjed, then F-clo ( XP 𝐵 ) entails F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) , and vice versa. 67 but Patrick didn’t say exactly how huge [the suitcase that Andy has] is 𝑢 . • F-clo ( XP 𝐵 ) = ∃𝑒[ Andy has a huge d suitcase ] • XP 𝐹 presupposes that there is a unique suitcase. • As long as we take it for granted that the presupposition of XP 𝐹 is

Semantic Identity and Island Evasion ii • We can ensure that the evasion source counts as identical if we make a minor modifjcation to e-GIVENness. (92) e-GIVENness XP 𝐵 , and… • Informally, 𝛽 strawson entails 𝛾 , if where 𝛾 ’s presuppositions are satisfjed, 𝛽 entails 𝛾 . 68 A constituent XP 𝐹 counts as e-GIVEN ifg XP 𝐹 has a salient antecedent a. XP 𝐵 Strawson entails F-clo ( XP 𝐹 ) . b. XP 𝐹 entails F-clo ( XP 𝐵 )

Varities of island evasion • Broadly, there are three kinds of evasion source we (arguably) need to consider in order to account for the full range of cases. • short sources • cleft sources • predicational sources 69

Short sources (93) They hired [someone who speaks a Balkan language] - guess which! • We call this a short source . • Merchant (2001) proposes that short sources are employed to evade propositional islands that is, islands which correspond to propositional domains (e.g., relative clauses, adjunct clauses, CP-complements to head nouns, and coordinated propositional structures). • They satisfy ellipsis identity by taking the clausal island, not the larger structure containing it, as an antecedent. • But Merchant notes these would satisfy his semantic identity condition just like regular sluices if the pronoun is coindexed with the DP that binds the gap position, on what he identifjes as an E-type construal. 70 a. which he 𝑦 speaks! ✓ b. which they hired someone who speaks! ✗

Short sources ii • It is often the case that ellipsis allows for construals where the targeted antecedent is a small, non-isomorphic subpart of a larger structure, as is required for short source interpretations. but I don’t remember when I met him. 71 (94) a. John seems to me [ antecedent 𝑢 to be lying about something], but I don’t know what he is lying about. b. I remember [ antecedent PRO meeting him],

Clefts • This is the species of copular clause which is used in cleft constructions, where the subject is an expletive-like pronoun like it and the postcopular XP is the pivot of the cleft relative which modifjes it and which is is missing in so-called truncated clefts. (95) They hired someone who speaks a Balkan language • Cleft sources can be considered to be an additional evasion strategy if we assume with Mikkelsen and others that so-called truncated clefts are not necessarily derived by eliding the relative clause that follows the pivot in the non-truncated counterparts, but rather that they can be simple copular constructions in which the pivot is base-generated in its surface position 72 • guess which it was 𝑢 !

Evidence for clefts: P-or-Q sluices • See Barros (2014) (96) Either something’s on fjre, or Sally’s baking a cake, but I don’t know which Δ. (97) Either something’s on fjre, or Sally’s baking a cake, but I don’t know which it is. • As Barros shows, the cleft-based analysis of disjunction sluices receives strong support from the fact that they are only possible in languages that allow cleft continuations, such as English, German, Spanish and Portuguese. 73

P-or-Q sluices ii of.the znayu know {chto/ what kakoy/ which kakoe which iz dvuh/ ne two kakoe which kotoraja} situation immeno exactly (eto). it not I • in languages like Russian and Polish, on the other hand, both the bake disjunction sluice and the cleft continuation are ungrammatical. (7) *ili or Sally Sally opjat’ again pechet tort ya cake ili or chto-to something gorit, burns, no but 74

P-or-Q sluices iii which.nom cake, aber but ich I weiß nicht, know not, welches von again of.the beiden two (es (it ist). is) “Either something is on fjre or Susi is baking a cake again, but I don’t know which.” Kuchen, wieder • The cleft source analysis is further supported by the fact that in brennt languages with morphological case like German, the sluicing remnant shows up in nominative case, the same case which is assigned to cleft pivots. (8) Entweder Either es it burns bakes wo (some)where oder or die the Susi Susi backt 75

Cleft sources and P-stranding • Other arguments in favour of allowing ellipsis sites to contain cleft structures come from Vicente (2008) and others, who posit cleft sources to account for apparent P-stranding violations under sluicing in non-P-stranding languages. • Potsdam (2007), who shows that Malagasy sluicing is based on a pseudocleft structure, which would require broadly similar departures from isomorphism in satisfying ellipsis identity. • I’ll come back to P-stranding later. 76

Predicational sources • The second copular source which we consider here is called the predicational source , in which the remnant originates as the pivot of a predicational copular sentence. • The subject of a predicational source is an E-type pronoun which covaries with an argument in the antecedent, and the postcopular XP is a predicate which is predicated of the subject. was. • Predicational sources are generally non-isomorphic with their antecedent and so we need to motivate the proposal that this kind of non-isomorphism is tolerated. Fortunately there are independent reasons to believe that predicational sources must be possible under sluicing. 77 (98) Andy brought a huge suitcase, just wait until you see exactly how huge it

Predicational sources ii • Unconditional sluicing (see Elliott & Murphy 2016) (99) John will kiss anyone after the fjrst date, it doesn’t matter who (100) John will fjght any man, no matter how tall a…. how tall he is 𝑢 b.#/*… how tall John will fjght a t man/fjghts a 𝑢 man c.#… how tall a man John will fjght 𝑢 78 a …who they are 𝑢 b. #… who John will kiss/kisses 𝑢 after the fjrst date

Predicational sources iii • Non-intersective adjectives (see Barros, Elliott & Thoms 2014) • We will say that hard is non-predicative under its non-intersective reading, since the non-intersective reading disappears when hard is used as a predicate. 79 (101) #The worker is hard. ✗ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective (102) The problem is hard. ✓ intersective (103) The library hired a hard worker. ✓ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective (104) How hard a worker did the library hire? ✓ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective (105) The library hired a very hard worker. ✓ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective

Predicational sources iv • non-intersective reading is unavailable when hard is used as a predicate. Consequently, if a predicational source underlies adjectival left-branch sluices in English, we make the prediction that a non-intersective reading should be unavailable, tracking the unavailability of a non-intersective reading with an overt predicational continuation (106) #The library hired a hard worker, but I don’t know exactly how hard the worker was 𝑢 . (107) #The library hired a hard worker, but I don’t know exactly how hard. (108) The library hired a hard worker, but I don’t know exactly how hard a 80 ✗ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective ✗ non-intersective/ ✗ intersective worker the library hired t. non-intersective/ ✗ intersective

Predicational sources v • The experiment just conducted for English can be replicated even more cleanly with Romance, as in these languages whether or not nouns receive the non-intersective reading depends on whether they appear post- or pre-nominally. • vecchio (‘old’) in Italian: • when it appears post-nominally it receives an intersective reading, ascribing to the friend in question the property of being old. • when it appears pre-nominally on the other hand, it receives a non-intersective reading, where, old modifjes the length of the friendship. 81

Predicational sources vi amico. intersective/*non-intersective “the friend is old” old. vecchio. is è the.friend L’amico (11) *intersective/non-intersective “an old friend” friend. old (9) vecchio an un (10) intersective/*non-intersective “an old friend” old. vecchio. friend amico a un 82

Predicational sources vii (14) macchina car 𝑢 𝑗 𝑢 costosa, expensive, Gianni? John? “How expensive a car did John buy?” Quanto una How é is costosa expensive la the macchina? car? “How expensive is the car?” a bought (12) macchina *[Quanto [How costosa] 𝑗 expensive] ha has comprato bought una a car comprato 𝑢 𝑗 , 𝑢 , Gianni? John? “How expensive a car did John buy?” (13) *Quanto 𝑗 How ha has 83

Predicational sources viii quanto *Ho (18) intersective/*non-intersective “I met a very old friend of John’s, but I don’t know how old the friend is.” the.friend. l’amico. old vecchio is è how know incontrato so not non but ma John Gianni of di old.very vecchissimo Have met amico so *intersective/*non-intersective “I met a very old friend of John’s, but I don’t know how old.’ the.friend. l’amico. old vecchio is è how quanto know not un non but ma John, Gianni, of di friend amico old.very vecchissimo a friend a (15) John (16) intersective/*non-intersective “I met a very old friend of John’s, but I don’t know how old.” how. quanto. know so not non but ma Gianni Have of di old.very vecchissimo friend amico a un met incontrato Have Ho *Ho incontrato un not met incontrato Have Ho (17) *intersective/*non-intersective “I met a very old friend of John’s, but I don’t know how old.” how. quanto. know so non met but ma John, Gianni, of di friend amico old.very vecchissimo a un 84

Multiple sluicing and repair • Multiple sluicing gives us another way to control for evasion sources. (109) Someone was talking about something, but I don’t know who about what. • Cleft sources are incompatible with multiple sluicing because an underlying shallow cleft (a copular clause without the cleft relative) only makes available one argument which can be a wh -phrase and thus become a sluicing remnant, namely the postverbal argument. • Predicational sources are similarly inappropriate, since they only make available one argument except on an equative reading, which ought to be easily teased apart from other target readings. 85 (110) … who it was 𝑢

Multiple sluicing and short sources • As for short sources, these can be controlled for by careful selection of our correlates: if one is inside the island and one outside of it, we should remove the short source analysis for the sluice, since the short source wouldn’t provide an extraction site for the island-external correlate. (19) [ [correlate 1] ... [island ... [correlate 2] ... ]] antecedent t 1 ... [island ... t 2 ... ]] sluice 86 *[wh 1 wh 2 ...

Multiple sluicing and short sources ii antecedent sluice ... ] t 2 ... t 1 [correlate 1] ... [correlate 2] ... ] • apparent repair should resurface if both correlates are in the island, ... [island ... [ (20) requiring island extraction since the short source could provide both remnants without ever 87 [wh 1 wh 2 ...

Multiple sluicing and short sources iii • The following examples show that the predictions of the evasion approach are borne out for English. (21) *One of the panel members wants to hire someone who works on a Balkan language, but I don’t know which panel member on which language. (22) *One of the students brought a book to talk to one of the professors about, but I don’t know which student to which professor. 88

Multiple sluicing and short sources iv • The other prediction, that apparent repair should be attested when a short source would be possible, is demonstrated below. (23) a. They hired someone who teaches an infamous course every year at a famous university, but I forget which course at which university. b. which university] 𝑘 . 89 ...but I forget [which course] 𝑗 she teaches 𝑢 𝑗 every year 𝑢 𝑘 [at

Contrastive sluicing and island repair • As observed by Merchant (2008) and others, island efgects re-emerge in contrastive sluicing, providing strong evidence for isomorphic elided syntactic structure. (111) Abby wants to hire someone who speaks greek, speaks. 90 but I’m not sure which other language Abby wants to hire someone who

Contrastive sluicing and island repair ii • Griffjths and Liptak (2014) aim to account for the difgerent between contrastive and non-contrastive sluicing in terms of scopal parallelism syntactic identity. (112) Scopal parallelism in ellipsis Variables in the antecedent and elided clause are bound from parallel positions. • Like Merchant (2008), Griffjths and Liptak assume that island violations inside of ellipsis sites are repaired . 91

Contrastive sluicing and island repair iii • They note that scopal parallelism is easily satisfjed in ordinary (non-contrastive instances of sluicing). (113) They want to hire someone who speaks a Balkan language (114) [a Balkan language] 𝜇𝑦 they want to hire someone who speaks 𝑢 . • Griffjths and Liptak claim that this is unproblematic, since specifjc indefjnites such as a Balkan language can take exceptional scope out of islands. 92 but I’m not sure which they want to hire someone who speaks 𝑢 (115) which 𝜇𝑦 they want to hire someone who speaks 𝑢

Exceptional scope • This has a reading according to which a certain aunt takes scope above each boy , which requires a certain aunt to take scope out of the island. • Griffjths and Liptak assume that this leads to a variable binding confjguration in which a certain aunt scopes out of the island and binds a variable inside of the island (although this is not unproblematic – see Charlow 2014). 93 (116) Each boy will be upset [ antecedent if a certain aunt dies young].

Contrastive sluicing iv • Turning back to contrastive sluicing, scopal parallelism forces the following confjguration: (117) They want to hire someone who speaks Greek, but I’m not sure which other language. (118) *Greek 𝜇𝑦 they want to hire someone who speaks 𝑦 . • On the basis of evidence from Hungarian, Griffjths and Liptak claim that focus-driven A’-movement cannot violate islands. 94 (119) which other language 𝜇𝑦 they want to hire someone who speaks 𝑦 .

Hungarian focus movement ii rel.who.a Janos only introduced the man who Juli admires to Zsuzsa. 𝑢 𝑢 Zsuzsa.dat Zsuzsának pv be introduced mutatta admires] csodál] Juli Juli akit • One way for an island-internal focus to take wide scope is to pied-pipe [ island [ island man.a férfit the a that.a azt only (csak) Janos János (24) the entire island overtly . 95

Hungarian focus movement the only Juli Julu mutatta introduced be pv Zsuzsásnak Zsuzsa.dat azt that.a a férfit Janos man.a [ island [ island akit rel.who.a 𝑢 𝑢 csodál]. admires] Janos only introduced the man who Juli admires to Zsuzsa • Hungarian therefore constitutes the overt correlate of Griffjths and Liptak’s analysis of English. (csak) * János • A focus cannot undergo movement from inside of an island, rather a mutatta dummy demonstrative must be inserted. (25) János Janos (csak) only azt that a a férfit the man (26) be pv Zsuzsának, Zsuzsa.dat [ island [ island akit rel.who.a Juli Juli csodál]. admired] Janos only introduced the man who Juli admires to Zsuszana. 96

Contrastive sluicing v • According to Griffjths and Liptak, the availability of exceptionally-scoping of focus is English is illusory - it in fact involves covert pied-piping. (120) They only want to hire someone who speaks Greek. (121) only [someone who speaks Greek] 𝜇𝑦 they want to hire 𝑦 • Such a derivation is not available for contrastive sluicing, as it would violate scopal parallelism. • The following satisfjes scopal parallelism but violates independent constraints on pied-piping. (122) *They want to hire someone who speakers Greek but I don’t remember 97 [someone who speaks which other language] they want to hire 𝑢

Syntactic constraints on sluicing 98

Case-matching know will wants jemanden someone.acc loben, praise aber but sie they wissen nicht, Er not { *wer { who.nom | | wen who.acc | | *wem } who.dat } He wants to fmatter someone, but they don’t know who. he (28) (27) wissen Er he will wants jemandem someone.dat schmeicheln, fmatter, aber but sie they know He wants to fmatter someone, but they don’t know who. nicht, not { *wer { *who.nom | | *wen *who.acc | | wem } who.dat } 99

Case-matching ii who.acc wissen know nicht, not { *wer { who.nom | | wen | Sie | *wem } who.dat } er he loben praise will. wants. They don’t know who he wants to praise. They (30) (29) *wen Sie They wissen know nicht, not { *wer { *who.nom | | *who.acc They don’t know who he wants to fmatter. | | wem } who.dat } er he schmeicheln fmatter will. wants. 100

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.