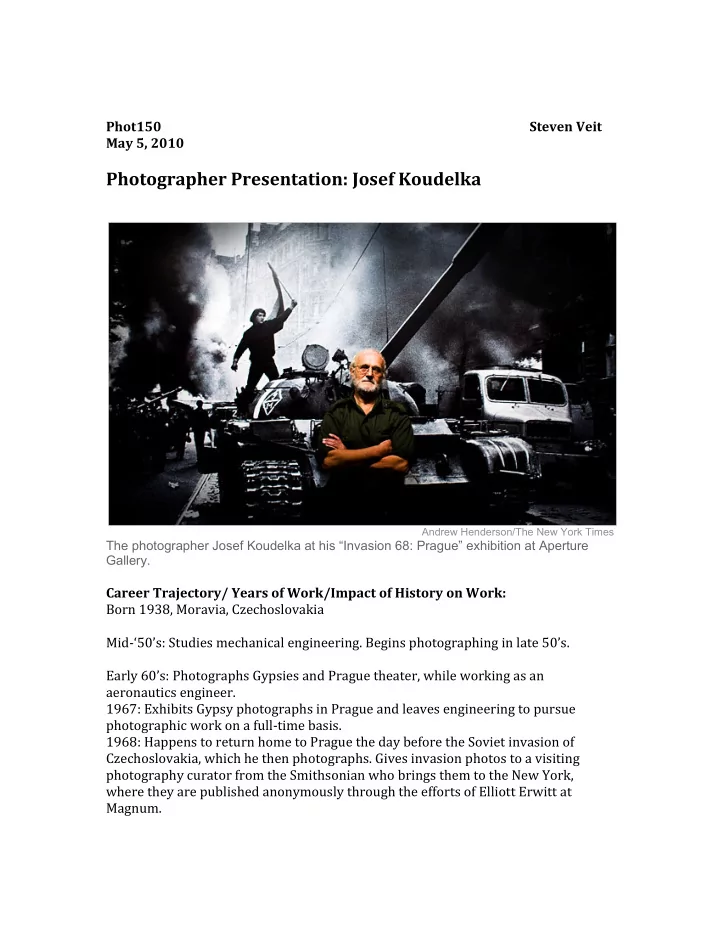

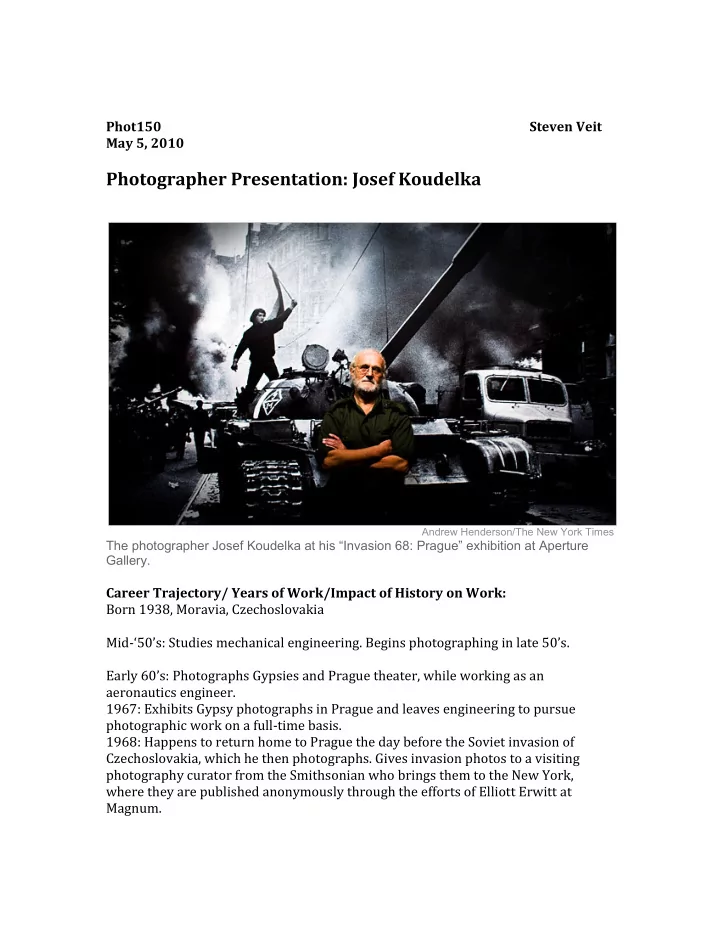

Phot150 Steven Veit May 5, 2010 Photographer Presentation: Josef Koudelka Andrew Henderson/The New York Times The photographer Josef Koudelka at his “Invasion 68: Prague” exhibition at Aperture Gallery. Career Trajectory/ Years of Work/Impact of History on Work: Born 1938, Moravia, Czechoslovakia Mid‐‘50’s: Studies mechanical engineering. Begins photographing in late 50’s. Early 60’s: Photographs Gypsies and Prague theater, while working as an aeronautics engineer. 1967: Exhibits Gypsy photographs in Prague and leaves engineering to pursue photographic work on a full‐time basis. 1968: Happens to return home to Prague the day before the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, which he then photographs. Gives invasion photos to a visiting photography curator from the Smithsonian who brings them to the New York, where they are published anonymously through the efforts of Elliott Erwitt at Magnum.

1970: Leaves Czechoslovakia for London and is granted asylum in UK. During ‘70’s, travels throughout Europe photographing Gypsies and urban and rural landscapes. 1975 :“Gypsies” published. 1987: Becomes French citizen, photographs panoramic images of French northern‐ coastal landscape, particularly the changes caused by construction of the channel tunnel. 1988: “Exiles” published. 1990: Visits Czechoslovakia after 20 years of exile, photographs eastern Europe, particularly the devastated ore‐mining region of northern Bohemia, southern Germany, and Poland. 1994: “The Black Triangle” published. Photographs panoramas of South Wales. 1999: “Chaos” published. Since 2000, has continued photographing panoramic images of landscapes. Impact of Koudelka’s Czech Nationality on his Work: The Czech theater scene and the Czech Gypsy community were important early influences. His Czech nationality led directly to his fortuitous return to Prague just in time to witness the 1968 Soviet invasion, which was arguably the key event in defining his photographic career. Much, if not all, of Koudelka’s subsequent work appears to have been strongly influenced by first, his Czech nationality, and later, his stateless, wandering condition of exile from his Czech homeland. His Gypsy‐like rootlessness has undoubtedly informed his later work, documented in his books “Gypsies,” “Exiles,” “The Black Triangle” and most recently, “Chaos.” These bodies of work highlight, on the one hand, the conditions of communities on the edge of society, and on the other, the destructive changes to the landscape brought about by industrial development. Development of Koudelka’s Interest in Photography: His early work appears to have developed out of opportunities and interests pursued according to a combination of happenstance and deliberate plan. At age 12, after seeing an amateur photographer’s work, he acquired a 6x6 camera with which he made contact prints and various cropped images, exploring compositional possibilities and making what he identifies as his first panoramic images. 1 Acquaintances in the artistic and theater community encouraged him to travel, to photograph, and later, to exhibit and publish his work. Although he never studied art or photography formally, he acknowledges being inspired generally by viewing the work of artists in museums that he visits on his travels. Other Artists’ Influences on Koudelka: Koudelka has stated that he has never had heroes in photography or elsewhere, and acknowledges no major influences. 2 He does, however, credit the Czech photographer and critic Jiri Jenicek with providing him with much‐appreciated encouragement, and also with introducing him to the photography critic and curator

Anna Farova, with whom he collaborated on various exhibitions. Karova also showed him the work of the Farm Security Administration photographers, whom Koudelka says impressed him. Koudelka also knew Henri Cartier‐Bresson (HCB) even prior to his (Koudelka’s) association with Magnum, and acknowledges HCB’s advice and support. Koudelka has said that he was often critical of HCB’s work, though he believed that HCB valued this criticism. 1 “Style” and Main Subject Matter: Koudelka’s style emphasizes both people (earlier work) and landscapes (later work) that exist in the frame as images of the ordinary seen in an extraordinary way. He has a direct and literal style, though his compositional eye more often than not yields a vision of the novel and unexpected. In the Gypsy series, for example, he causes us to wonder how these figures came to co‐exist in the picture space, though they seem to fit in it plausibly enough. Images that are natural enough, perhaps, but with elements unnervingly juxtaposed. His main subject matter has been organized by multi‐year projects, resulting in several major exhibitions and in the publications mentioned above. Photographic motivation, philosophy: These quotes speak to Koudelka’s motivation and philosophy: “I have to shoot three cassettes of film a day, even when not 'photographing', in order to keep the eye in practice.” Josef Koudelka, quoted in “On Being a Photographer : A Practical Guide” (3rd Ed.) by David Hurn, in Conversation with Bill Jay, New York: Lenswork, 2001. “What matter most to me (...) is to take photographs; to continue taking them and not to repeat myslef. To go further, to go as far as I can.” 3 Why Koudelka’s art speaks to me: I find Koudelka’s work remarkable in that it explores in image after image a way of seeing that transcends the ordinary reality of everyday experience yet seems nevertheless to be securely grounded in that reality. Koudelka’s images seem, more often than not, novel and unusual, while at the same time being entirely believable. Looking at a Koudelka image, for example, one wonders how that scene, simultaneously odd yet composed of ordinary, recognizable elements, could possibly exist, yet one has no doubt that it did in fact exist in the space before Koudelka’s camera. Could such natural montages, such perfectly composed images be revealed to just any onlooker? Or is there something privileged about Koudelka’s vision that enables him to see what we wouldn’t ordinarily, or perhaps ever see, even if thrust into the same setting and instructed to look with an awareness open to every possibility? Technical aspects: Used a Rolleiflex for early work, then an Exacta slr with a 25mm lens for photographs of Gypsies and of the Prague invasion. For later panoramic work, Koudelka used a 6x17 medium format camera. He admits to having tried color once,

but having given it up with no regrets after not liking it at all. Koudelka mentions that his physical viewpoint was influenced by his having obtained in 1963 one of the first wide‐angle lenses available in Czechoslovakia for the 35‐mm format, an East‐ German 25mm lens. 1 He says in one of his interviews with Karel Hvizdala that this lens “changed my vision,” and enabled him to “work in the small spaces where Gypsies lived…to separate the essential from the unessential, and to achieve in bad light the full depth of field which I had always wanted.” 1 Interestingly, he stated in this interview that he stopped using the wide‐angle lens when he left Czechoslovakia, after he began to feel that it was restricting his creativity. What can we learn from the work of Josef Koudelka? Koudelka has approached his subject matter with a singular vision that connects only occasionally with other currents in the larger world of photographic artistry. His images of Gypsies and others outside the mainstream of society exist as naturally‐occurring montages of the never‐before‐imagined mundane. A horse, a dog, a bather, a child, a group of men in suits, each viewed in a strange world that is at once foreign to us and at the same time somehow familiar. Similarly, Koudelka’s landscapes give us a new way of seeing the human‐made and natural environment. Industrial, debris‐strewn chaos takes on a mystical, otherworldly beauty, occasionally enhanced by combination with other images in a 2‐ or 3‐image format. Simply put, as with all great photographers, what we can learn from Koudelka is nothing less than how to see in a new way.

Selected Images by Joseph Koudelka: Prague, 1968 Spain, 1971

France, 1973 Portugal, 1976

Recommend

More recommend