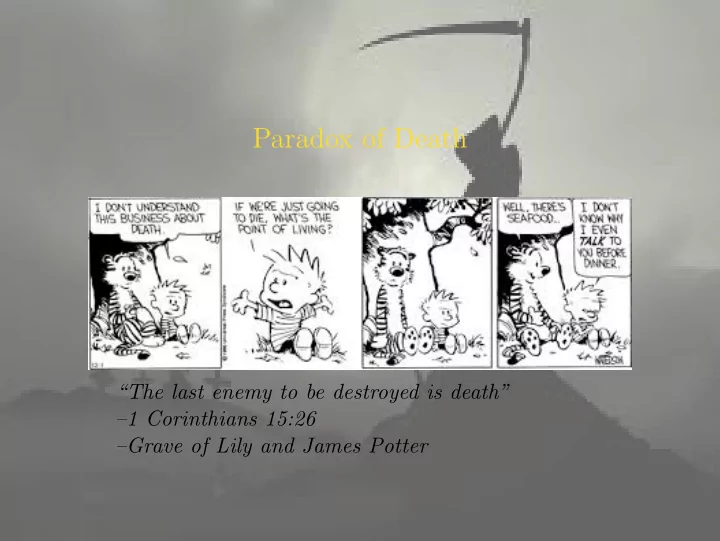

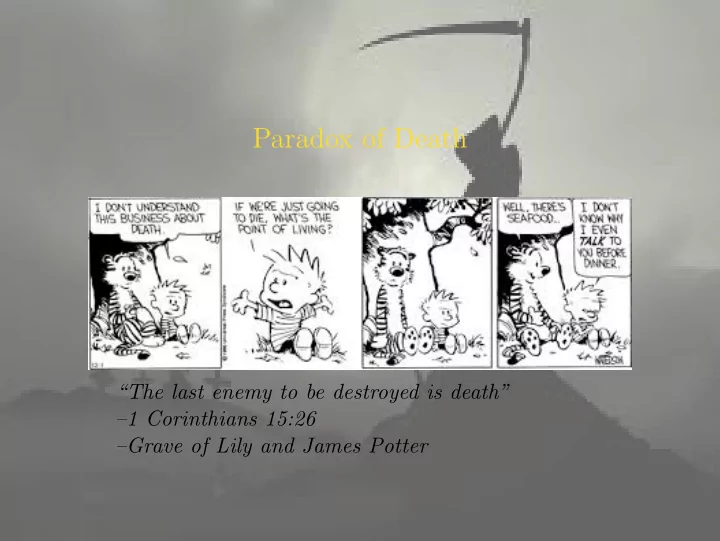

Paradox of Death “The last enemy to be destroyed is death” –1 Corinthians 15:26 –Grave of Lily and James Potter

Death is bad • Despite its inevitability, we spend massive amounts of time, money, and effort, trying to fight death • Dozens of times a day, you make choices which are designed to prevent death • Despite that, there are lots of philosophers who think there are compelling reasons that death cannot be bad (at least for the person dying) • According to these philosophers, even if we who survive dislike death because we miss our loved ones, we should not think the person who died is any worse off than they would have been had they survived.

Epicurus’ Argument 1. My death is not bad for me when I am alive. 2. My death is not bad for me when I am dead. 3. If something is not bad for me when I am alive, and not bad for me when I am dead, then it is not bad for me. 4. Therefore, my death is not bad for me. (1, 2, 3)

Epicurus’ Argument • The crucial premise seems to be premise 2, • Epicurus’ reasoning is that (i) When something dies it ceases to exist (ii) If something does not exist, nothing can be bad for it (iii) Therefore, nothing can be bad for something that is dead • You might not agree with this reasoning, but it at least raises the questions ◮ When is death bad for a person? ◮ Why is death bad for that person at that time?

When is death bad? • One way death could be bad for the person while alive is the anticipation of it. • However, if death is not bad, then pain from the anticipation of death would be irrational and should be avoided. • If you were experiencing great distress over the fact that a coin flip was going to come up tails tomorrow, that would be evidence of an anxiety disorder. • The correct response to the coin situation is to get help so that you are no longer anxious over non-bad things; if the only bad thing about death is anticipation, then we should respond in the same way with help to no longer fear a neutral occurrence. • It thus seems plausible that the badness of death needs to be after the death occurs. • An important consequence of this is that the badness cannot something like pain which must be felt–it must be a different kind of badness.

What would have happened... • One tempting strategy is to analyze the badness of death is by contrasting the non-existence of death to the good things in life they would have had if they had not died when they did. • Suppose Sierra dies in a car crash at age 18. If she had not died in that car crash, she would have gone on to live a relatively happy 70 more years (with only 2 bad years at the end). We can then say that her death is bad because she would have had many more good things and was deprived of those good things. • Deprivation Theory helps to make sense of why we consider dying young to be more tragic than dying in middle age or dying old–they were deprived of more life • Similarly, we are more sad when someone dies who would have had a happy life, as opposed to someone who was suffering intensely.

What would have happened... • Deprivation theory − the claim that the badness of death is based on the absence of good things we otherwise would have − tells us what is bad about about death, but it doesn’t really answer when that lack/absence is bad for us • One suggestion is to say that some bad things don’t have to occur at a time or that they occur at all times (these responses deny premise 3 of Epicurus’ argument) • A different suggestion is to say that it is bad for you at precisely the years you would have existed, but it is not clear how it can be bad for you in those years.

Objections • Deprivation theory seems to have some clearly wrong consequences • Suppose Sienna died in a car crash at 18, but unlike Sierra, had Sienna survived that car crash she would have died in a different car crash the next day. Are we really to suppose Sienna’s death is less bad than Sierra’s? • If a child is born with a severe medical condition that kills them at an early age, we consider that bad, even though it is well known that their medical condition was going to kill them some time early in life

Objections • Suppose you find out that you have a rare medical condition that will kill you in a week. You and all your family are sad. However, I care about you, so I hire some mafiosos and pay them $1 million so long as they solemnly swear that if you recover next week, they will kidnap you and torture you for the rest of your life. • By deprivation theory, I have removed all the harm of death and in fact made your death a very good thing since you are not deprived of good experiences and are instead merely missing out on horrible pain • Would you and your family find comfort upon learning of my actions?

Revising Deprivation Theory • It thus seems we need to modify deprivation theory in some ways so that the mere hiring of mafiosos does not remove all the badness of your death • One suggestion would be to no longer compare your non-existence to what would have happened, but instead to compare it to the average human life. • Thus, the child born with a terrible medical condition is deprived of a good life, even though had they survived that one event they might have died in a few months − the nature of the badness is that they are deprived compared to reasonable expectations of life. • Similarly, since Sierra and Sienna were otherwise identical with respect to what kind of life they could expect, their deaths were equally sad regardless of what car crashes would have happened the next day.

Objections • This version of deprivation theory seems to get other cases clearly wrong. • If I live until 100 with an incredibly happy life and am healthy enough to have 10 more good years, this theory would entail it is not bad for me to die because I am already above average expected life happiness. • If a technological breakthrough in 10 years allows everyone to start living ∼ 5,000 years, this theory would seem to imply that everyone who has ever died has had a particularly tragic existence because they had so much less than the average human life. • One might be tempted to respond by saying that we should only compare average to a certain group, but the more and more specific one gets with the comparison group, the more this becomes a version of the first deprivation theory.

Further Revisions • What if we think the deprivation is not based on what we would have had, but rather the mere deprivation of life itself? • Life, at least the life of a person, can seem to be an intrinsically good thing, so having more of a good thing would be good–death deprives us of that chance • On this position, any death would be bad regardless of what we had experienced thus far and what we would experience–its badness would be in depriving us the chance to go on • While this avoids the previous problems, it prevents us from saying seemingly plausible things, such as that dying at 18 is worse than dying at 98 • It also seems to entail that existing forever in horrible agony would be better than dying

What about Life After Death? • The previous 3 attempts assume that the badness of death is loss of a par, and they disagree as to how we determine what the good thing is that is lost with death (life, average expected happiness, subjunctive conditional happiness). • One might think that we are still around in an afterlife after death, in which case we do not need to merely treat death as an absence, but instead we can talk about what you are experiencing after death. • One concern for this view is that we often are sad for a person that died, even if we think they are in heaven and/or we are unsure of their eternal state • A different concern is that Christianity treats death as bad, an enemy to be defeated; if the goodness or badness of death was in what we were experiencing after death, one would think death would be a marvelously good thing for those in heaven.

An Attempted Answer • The badness of death does seem like it is in what we are missing as a result, but attempts to spell this out in terms of comparison seem to be deeply flawed. • There seems to be something right in the idea that life is good (and thus all death is sad), but that view also seem to go too far in that it entails suffering forever would be better than death. • Suppose we call Good Life life that is contributing to one’s overall well-being (i.e. I’m punting on what actually constitutes a good life) • We might then try to rework the last version of the deprivation theory as being that Good Life is good and any time one cannot have more of that it is bad.

Recommend

More recommend