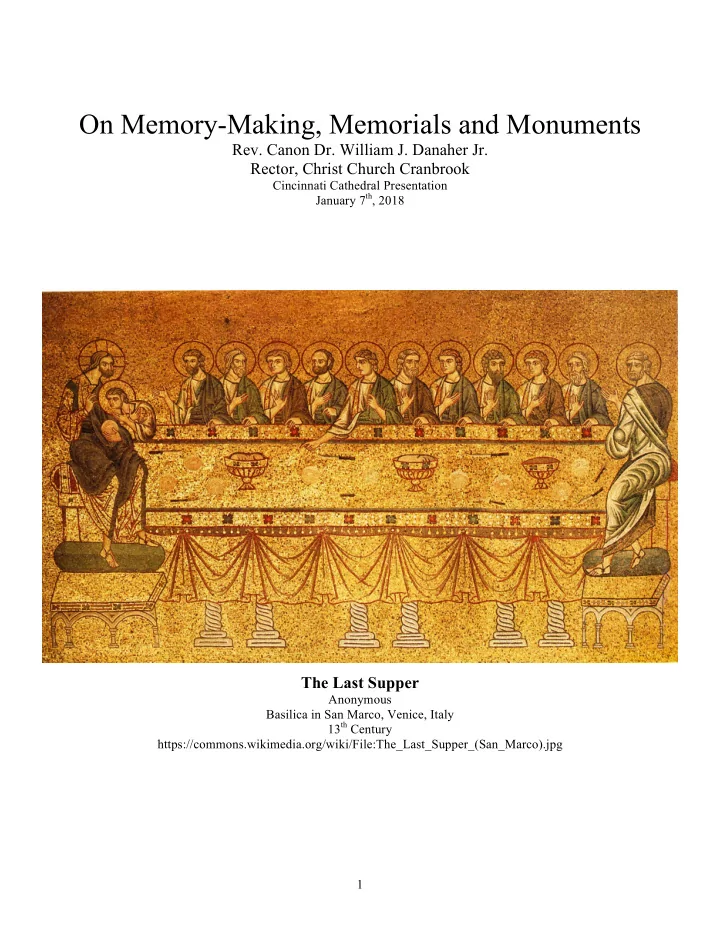

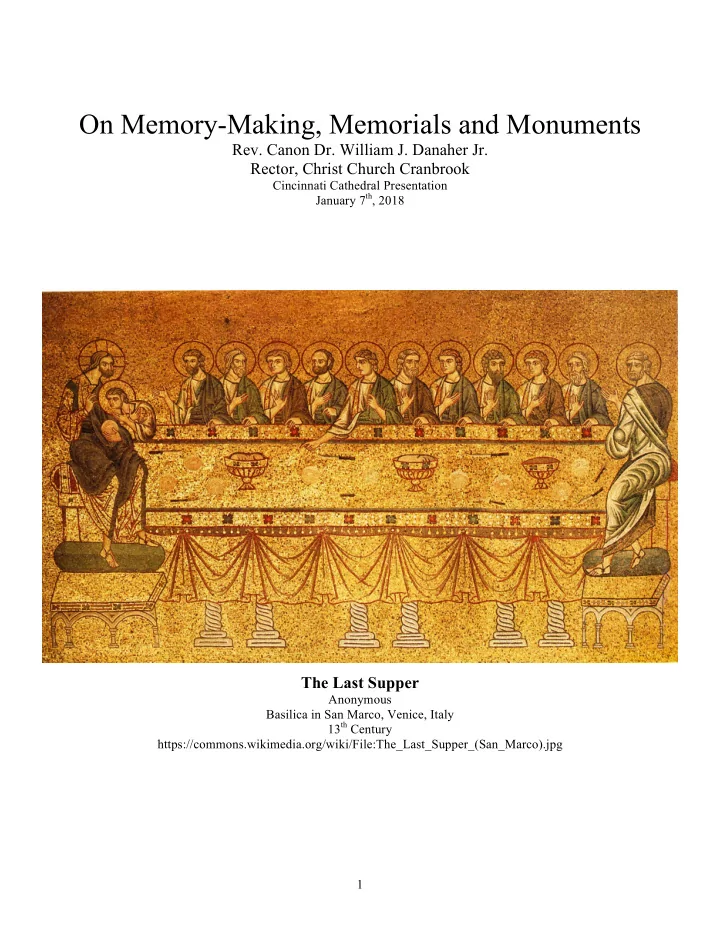

On Memory-Making, Memorials and Monuments Rev. Canon Dr. William J. Danaher Jr. Rector, Christ Church Cranbrook Cincinnati Cathedral Presentation January 7 th , 2018 The Last Supper Anonymous Basilica in San Marco, Venice, Italy 13 th Century https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Last_Supper_(San_Marco).jpg 1

Part 1: Memorials, Monuments, and Memory-Making A. Looking Back, Looking Forward: “Monuments” and “Memorials” are often taken as interchangeable terms, but they capture different approaches to representing and interpreting of the past. Arthur Danto (1924-2013), an enormously influential philosopher of Art, offers the following way to think of the two: “we erect monuments so that we shall always remember and build memorials so that we shall never forget.” The tension between “always remembering” and “never forgetting” is reflected in the fact that we have the “Washington Monument” [Fig. 1] and the “Lincoln Memorial” [Fig. 2] the latter being the site of the majority of demonstrations that appeal to the founding values and guiding virtues of our nation. From this nuance, the following rough-and-ready definitions emerge: 1. Monuments look back. They stabilize and crystallize the myths around a nation’s beginning. They make heroes and triumphs, victories and conquests, perpetually present. 2. Memorials look forward. They ritualize remembrance and point to ambitious projects and unfinished ends reached by values and virtues that require unending vigilance. B. Coded Messages: Whether lifting up mythic beginnings or ultimate endings, monuments and memorials both play the same cultural role in a community. Their stability, solidity, composition, and design are meant to communicate a coded message that holds together narratives, histories, memories, values, virtues, and identities. 1. James Young, who has written an enormously important book on Holocaust memorials and their meaning, offers the following description of this work: “By themselves monuments [and memorials] are of little value, mere stones in the landscape. But as part of a nation’s rites or the objects of a people’s national pilgrimage, they are invested with national soul and memory. For traditionally, the state-sponsored memory of a national past aims to affirm the righteousness of a nation’s birth, even its divine election. The matrix of a nation’s monuments [and memorials] emplots the story of ennobling events, of triumphs over barbarism, and recalls the martyrdom of those who gave their lives in the struggle for existence – who, in the martyrological refrain, died so that a country might live. In assuming the idealized forms and meanings assigned to this era by the state, memorials tend to concretize particular historical interpretations. They suggest themselves as indigenous, even geological outcroppings in a national landscape; in time, such idealized memory grows as natural to the eye as the landscape in which is stands. Indeed, for memorials to do otherwise would be to undermine the very foundations of national legitimacy, of the state’s seemingly natural right to exist.” ( The Texture of Memory , 1993, 2). 2. Because of this communicative function, memorials and monuments tend to obscure much of the past they try to retain and reveal. Consider, for example, Jacques-Louis David’s portraits of Napoleon crossing the Alps [Fig. 3] . Painted between 1801-1805, when Napoleon was at the height of his power, the artist depicts Napoleon with the athletic body of a young man (the model of which was the artist’s son) on a powerful charger confidently leading his troops into battle with the Austrian army. The Neo-classical style of the painting is meant to recall the strong, one-way messages made by monuments of the ideals and heroism of Napoleon as he leads the nation in its transition from Republic to Empire. 2

A very different depiction of this same event was painted by Paul Delaroche in 1850, which tries to tell a more truthful story [Fig. 4] . Here, instead of confident and youthful, Napoleon’s figure is painted as he was at that time – a middle aged man with over half his life over. The horse he is riding is exhausted, and on the verge of collapse – its hind legs are buckling. The troops, which were included among the viewers in David’s painting are now depicted as miserably following their leader as he gambles with their lives and their nation. Painted during the Second Republic (1848-1851), this painting is meant to instill in its audience a healthy suspicion of imperial designs and charismatic leaders – Delaroche’s intention, in other words, is to generate art that is counter-monumental. C. Memory-Making : Memorials and Monuments also become powerful forces of memory-making. They create – to use the title of a famous French sociologist, Maurice Halbwachs – a “collective memory” that in some ways is more important than the past that such landmarks validate. 1. Indeed, Halbwachs argues that it is only through their membership in religious, national, or class groups that people are able to acquire, recall, and share their memories at all. This social function, however, can mislead as much as lead. Halbwachs writes: “Society from time to time obligates people not just to reproduce in thought previous events of their lives, but also to touch them up, shorten them, or to complete them so that, however, convinced we are that our memories are exact, we give them a prestige that reality did not possess” ( On Collective Memory , 1992, 51) 2. For example, consider Ron MacDowell’s “The Foot Soldier,” a statue in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, Alabama [Fig. 5]. Based on an iconic photograph taken by Bill Hudson on May 4, 1963, during the Birmingham Campaign for Civil Rights, the stature shows a menacing white police officer turning loose a ferocious, wolf-like dog on a young African American teenager. Commissioned by Richard Arrington, the first African American mayor of Birmingham, the statue bears an inscription by Arrington that reads: “This sculpture is dedicated to the foot soldiers of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement. With gallantry, courage and great bravery they faced the violence of attack dogs, high powered water hoses, and bombing. They were the fodder in the advance against injustice, warriors of a just cause; they represent humanity unshaken in their firm commitment to liberty and justice for all.” However, the history of the photograph that inspired this memorial is complex and convoluted [Fig.6] . Published on May 4, 1963 in the New York Times , Hudson’s photograph seemed to depict the brutal and inhuman tactics being deployed by the Birmingham Police on the Nonviolent demonstrators led by The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. However, a close examination of the photograph, and the meeting it captured, in comparison to MacDowell’s statue reveal important differences. The actual encounter Hudson photographed was not of a protestor being attacked by a police dog. Rather it was of Walter Gadsden, who was not a foot soldier or activist, but a bystander who came to watch the demonstrations. The officer in the photograph, Richard Middleton, was – according to Gadsden and others – trying to restrain his dog, Leo, from biting Gadsden, as is evidenced by the fact that his left hand is trying to restrain his police dog to the point that Leo’s forelegs are off the ground. Finally, the relative size between Gadsden (6’4”) and Middleton (5’11”) in the photograph are reversed in the McDowell’s statue, which 3

Recommend

More recommend