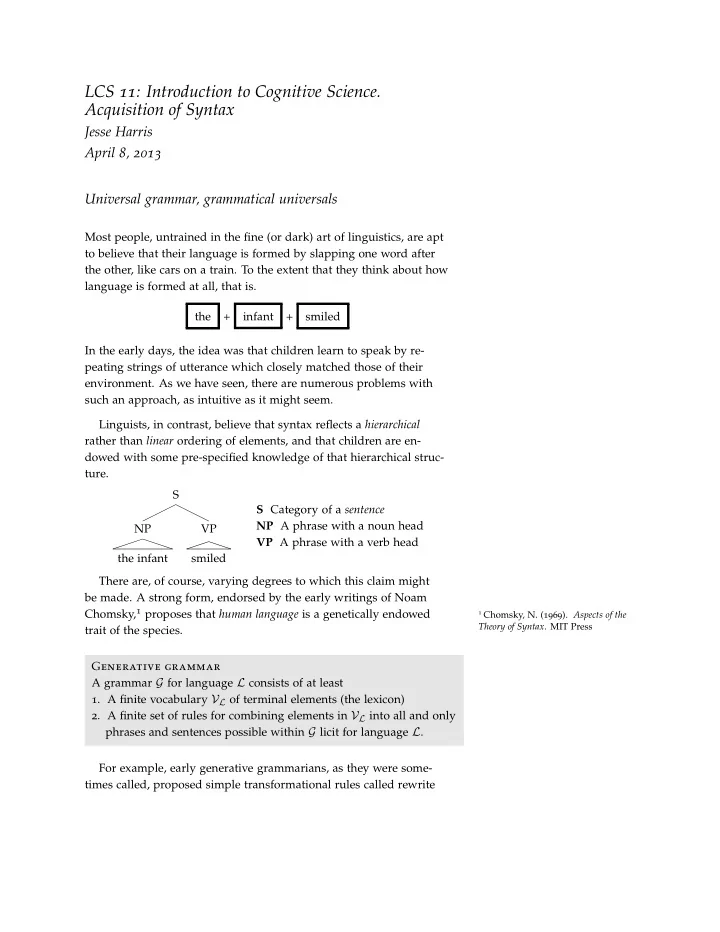

LCS 11 : Introduction to Cognitive Science. Acquisition of Syntax Jesse Harris April 8 , 2013 Universal grammar, grammatical universals Most people, untrained in the fine (or dark) art of linguistics, are apt to believe that their language is formed by slapping one word after the other, like cars on a train. To the extent that they think about how language is formed at all, that is. the + infant + smiled In the early days, the idea was that children learn to speak by re- peating strings of utterance which closely matched those of their environment. As we have seen, there are numerous problems with such an approach, as intuitive as it might seem. Linguists, in contrast, believe that syntax reflects a hierarchical rather than linear ordering of elements, and that children are en- dowed with some pre-specified knowledge of that hierarchical struc- ture. S S Category of a sentence NP A phrase with a noun head NP VP VP A phrase with a verb head the infant smiled There are, of course, varying degrees to which this claim might be made. A strong form, endorsed by the early writings of Noam Chomsky, 1 proposes that human language is a genetically endowed 1 Chomsky, N. ( 1969 ). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax . MIT Press trait of the species. G enerative grammar A grammar G for language L consists of at least 1 . A finite vocabulary V L of terminal elements (the lexicon) 2 . A finite set of rules for combining elements in V L into all and only phrases and sentences possible within G licit for language L . For example, early generative grammarians, as they were some- times called, proposed simple transformational rules called rewrite

lcs 11 : introduction to cognitive science . acquisition of syntax 2 rules, in which a string S could be rewritten in terms of its con- stituents: 2 2 These rewrite rules are for illustration purposes only. They are no longer in fashion in syntax. T oy rewrite grammar S → NP · VP NP → Det · N VP → V Given a vocabulary V L , we just insert terminal elements from V L into the rules above. T oy vocabularly Det the, a, some N girl, boy, infant V smiled, laughed, waited These simple rules allow us to produce Pulitzer Prize earning gems such as: 3 3 Obviously, this grammar is widely limited. For example, the speaker ( 1 ) a. The infant smiled would be unable to produce utterances with any kind of modification ( the fat b. A boy laughed infant ), conjunction smiled and laughed , c. Some puppy waited or verbs with additional arguments loved her teddy bear . Although this is clearly only a small fragment of English, Chom- sky’s claim was that we have knowledge of rules separate from either meaning or experience because we can substitute incoherent or even artificial elements into the rules, just so long as they are of the correct category. Chomsky’s famous example is given below. ( 2 ) Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. * Green sleep ideas furiously colorless. Despite the fact that such an utterance was surely never produced before 1957 , we seem to have a robust intuition 4 that it follows the 4 Sentences that are intuitively ungram- matical are traditionally demarcated rules of grammar, despite being semantically inconsistent, e.g., color- with a * sign. less and green seem semantically incompatible. 5 5 A similar point can be made with The task of the child, then, is to determine the grammar target Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky . language from all other possible languages. The claim of universal ‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves grammar is that the child’s task is constrained by an implicit knowl- Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, edge of what a language of universal grammar looks like, drastically And the mome raths outgrabe. reducing the search space during acquisition. The task of the child is, then, to be a kind of little linguist in search of a native language by relying on an abstract and unconscious understanding of what a possible human language is. One of the strongest general arguments for this approach is that children’s mistakes are seem to be constrained in kind. For exam-

lcs 11 : introduction to cognitive science . acquisition of syntax 3 ple, it seems that children seem to not violate certain universals on what are called transformations . A transformation is the idea that one sentence S 1 is systematically related to another sentence S 2 through an operation or series of operations. Some operations are allowed in some languages but not others, while other operations seem to be universal, in that they are available or active in all known human languages. A relatively clear case of relatedness between two syntactically distinct utterances is that of Topicalization in which something that is introduced as a new topic (that which is under discussion) appears in a non-canonical (unusual) position within the sentence: ( 3 ) I’ll eat ice cream. ( 4 ) Ice cream, I’ll eat. 6 6 Yes, this is a bizarre sentence to utter out of the blue. Try this context and The intuition is that ( 3 ) and ( 4 ) are related in a relatively simple see if you like it any better: A parent is trying to get her child to finish her green way and that we miss something important if we fail to capture that beans during supper before desert. The relationship. Simply put, ( 3 ) and ( 4 ) share a similar origin, such that parent coaxes the child, saying ’You should ( 4 ) is a result of applying a transformation which ‘moved’ the ele- eat your beans, I know you like them.’ In response, the child could reply ’ I don’t ment ice cream from object position to a topic position at the very want beans! But ice cream, I’ll eat.’ front of the sentence. ( 5 ) Ice cream, I’ll eat ice cream � Another argument for syntactic relatedness, and hence transfor- mations, is that the lexical restrictions imposed by a verb are obeyed even after a transformation has applied. For example, verbs seem to specify the number and type of arguments (nouns) that they appear with. A verb like eat is optionally intransitive, as it can appear with either an object noun or not. But if it does appear with an object, it must be understood as an edible object. ( 6 ) I’ll eat bricks. ( 7 ) # Bricks, I’ll eat. As Yang 7 points out, the greatest verbal humor hangs on the sim- 7 Yang, C. ( 2006 ). The infinite gift: How children learn and unlearn the languages of plest of ambiguities. the world . New York, NY: Scribner G roucho ’ s ambiguity I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I’ll never know. It’s never a good idea to explain a joke, but here goes: the phrase in my pajamas is structurally ambiguous in terms of what it modifies. Either it modifies the shooting event (option A) or it modifies the elephant (option B).

lcs 11 : introduction to cognitive science . acquisition of syntax 4 ( 8 ) Option A: Shooting occurred in pajamas: S NP VP I V NP PP shot an elephant in my pajamas In the second case, the ambiguity can be resolved like so: ( 9 ) Option B: Elephant was wearing the pajamas: S NP VP I V NP shot NP PP an elephant in my pajamas Option A more plausible, for a whole host of reasons – the joke is funny, some might say, because it forces us to reconsider the syntactic analysis that we originally assigned. As Yang observes, the ambiguity disappears in the question ver- sion: ( 10 ) Whose pajamas did you shoot the elephant in whose pajamas? � The idea is that languages, in general, seems to obey a constraint on movement which prohibits movement which result in stranding the head noun which is modified. Note, too, that the following ques- tion disambiguates the structure, in the other direction: ( 11 ) [Which elephant in my pajamas] did you shoot which elephant in my pajamas? � Amazingly, children, even 3 year olds, are not tempted by the inappropriate interpretation. Yet, surely, they were never taught such a rule. It seems that their implicit knowledge of language structure has guided their interpretation of the sentence.

lcs 11 : introduction to cognitive science . acquisition of syntax 5 Recursion As Deutscher discusses, 8 a central – and controversial – idea is that 8 Deutscher, G. ( 2011 ). Through the language glass: Why the world looks all human language is characterized by a sufficient and comparable different in other languages . Arrow Books degree of complexity. One of these measures of complexity is recur- sion which is, simply put, the capacity to embed one structure within another of the same kind. Relative clauses are prime examples. ( 12 ) The infant that smiled laughed � �� � relative clause We can add a simple rule to our toy grammar to illustrate the point: T oy rewrite grammar with relative clauses S → NP · VP NP → Det · N VP → V NP → C · S Here, the last rule allows us to introduce a structure (S) of the same kind into the one that we are already building. We can then generate increasingly complex examples with many, many layers of embedding. A simpler case is that of adjective stacking: ( 13 ) The great, happy, giant, fat, . . . , cooing infant smiled. T oy rewrite grammar with adjective stacking S → NP · VP NP → Det · N VP → V NP → C · S N → Adj · N Adj → Adj · Adj A controversial issue is whether all languages have the same sort of complexity and whether this complexity must involve syntactic embedding. Ultimately, it is an empirical question, with major conse- quences for syntactic theory.

Recommend

More recommend