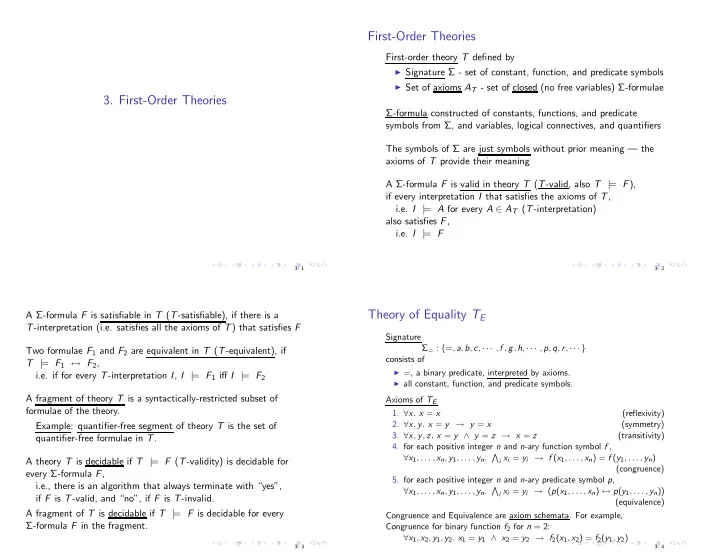

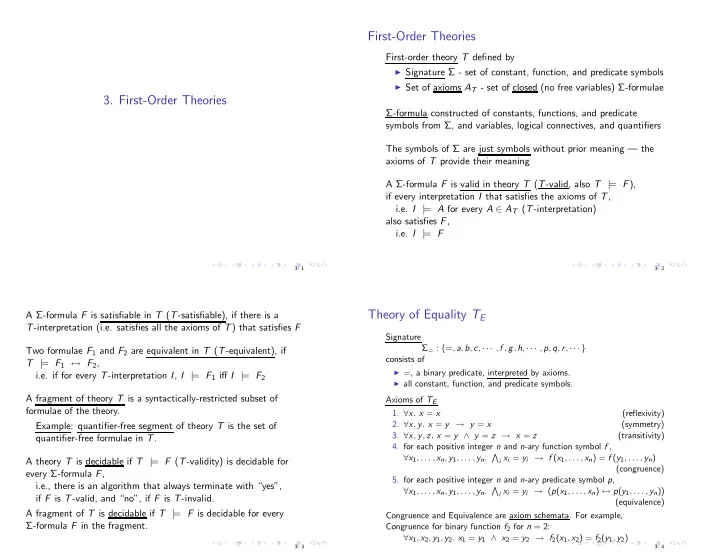

First-Order Theories First-order theory T defined by ◮ Signature Σ - set of constant, function, and predicate symbols ◮ Set of axioms A T - set of closed (no free variables) Σ-formulae 3. First-Order Theories Σ-formula constructed of constants, functions, and predicate symbols from Σ, and variables, logical connectives, and quantifiers The symbols of Σ are just symbols without prior meaning — the axioms of T provide their meaning A Σ-formula F is valid in theory T ( T -valid, also T | = F ), if every interpretation I that satisfies the axioms of T , i.e. I | = A for every A ∈ A T ( T -interpretation) also satisfies F , i.e. I | = F 3- 1 3- 2 Theory of Equality T E A Σ-formula F is satisfiable in T ( T -satisfiable), if there is a T -interpretation (i.e. satisfies all the axioms of T ) that satisfies F Signature Σ = : { = , a , b , c , · · · , f , g , h , · · · , p , q , r , · · · } Two formulae F 1 and F 2 are equivalent in T ( T -equivalent), if consists of T | = F 1 ↔ F 2 , ◮ =, a binary predicate, interpreted by axioms. i.e. if for every T -interpretation I , I | = F 1 iff I | = F 2 ◮ all constant, function, and predicate symbols. A fragment of theory T is a syntactically-restricted subset of Axioms of T E formulae of the theory. 1. ∀ x . x = x (reflexivity) 2. ∀ x , y . x = y → y = x (symmetry) Example: quantifier-free segment of theory T is the set of 3. ∀ x , y , z . x = y ∧ y = z → x = z (transitivity) quantifier-free formulae in T . 4. for each positive integer n and n -ary function symbol f , ∀ x 1 , . . . , x n , y 1 , . . . , y n . � i x i = y i → f ( x 1 , . . . , x n ) = f ( y 1 , . . . , y n ) A theory T is decidable if T | = F ( T -validity) is decidable for (congruence) every Σ-formula F , 5. for each positive integer n and n -ary predicate symbol p , i.e., there is an algorithm that always terminate with “yes”, ∀ x 1 , . . . , x n , y 1 , . . . , y n . � i x i = y i → ( p ( x 1 , . . . , x n ) ↔ p ( y 1 , . . . , y n )) if F is T -valid, and “no”, if F is T -invalid. (equivalence) A fragment of T is decidable if T | = F is decidable for every Congruence and Equivalence are axiom schemata. For example, Σ-formula F in the fragment. Congruence for binary function f 2 for n = 2: ∀ x 1 , x 2 , y 1 , y 2 . x 1 = y 1 ∧ x 2 = y 2 → f 2 ( x 1 , x 2 ) = f 2 ( y 1 , y 2 ) 3- 3 3- 4

Natural Numbers and Integers T E is undecidable. The quantifier-free fragment of T E is decidable. Very efficient Natural numbers N = { 0 , 1 , 2 , · · · } algorithm. Integers Z = {· · · , − 2 , − 1 , 0 , 1 , 2 , · · · } Semantic argument method can be used for T E Example: Prove Three variations: F : a = b ∧ b = c → g ( f ( a ) , b ) = g ( f ( c ) , a ) T E -valid. ◮ Peano arithmetic T PA : natural numbers with addition and Suppose not; then there exists a T = -interpretation I such that multiplication I �| = F . Then, ◮ Presburger arithmetic T N : natural numbers with addtion ◮ Theory of integers T Z : integers with + , − , > 1 . I �| = F assumption 2 . | = a = b ∧ b = c 1, → I 3 . �| = g ( f ( a ) , b ) = g ( f ( c ) , a ) 1, → I 4 . | = a = b 2, ∧ I 5 . I | = b = c 2, ∧ 6 . I | = a = c 4, 5, (transitivity) 7 . I | = f ( a ) = f ( c ) 6, (congruence) 8 . I | = g ( f ( a ) , b ) = g ( f ( c ) , a ) 4, 7, (congruence), (symmetry) 3 and 8 are contradictory ⇒ F is T = -valid 3- 5 3- 6 1. Peano Arithmetic T PA (first-order arithmetic) We have > and ≥ since 3 x + 5 > 2 y write as ∃ z . z � = 0 ∧ 3 x + 5 = 2 y + z Σ PA : { 0 , 1 , + , · , = } 3 x + 5 ≥ 2 y write as ∃ z . 3 x + 5 = 2 y + z The axioms: Example: 1. ∀ x . ¬ ( x + 1 = 0) (zero) ◮ Pythagorean Theorem is T PA -valid ∃ x , y , z . x � = 0 ∧ y � = 0 ∧ z � = 0 ∧ xx + yy = zz 2. ∀ x , y . x + 1 = y + 1 → x = y (successor) ◮ Fermat’s Last Theorem is T PA -invalid (Andrew Wiles, 1994) 3. F [0] ∧ ( ∀ x . F [ x ] → F [ x + 1]) → ∀ x . F [ x ] (induction) ∃ n . n > 2 → ∃ x , y , z . x � = 0 ∧ y � = 0 ∧ z � = 0 ∧ x n + y n = z n 4. ∀ x . x + 0 = x (plus zero) Remark (G¨ odel’s first incompleteness theorem) 5. ∀ x , y . x + ( y + 1) = ( x + y ) + 1 (plus successor) Peano arithmetic T PA does not capture true arithmetic: 6. ∀ x . x · 0 = 0 (times zero) There exist closed Σ PA -formulae representing valid propositions of 7. ∀ x , y . x · ( y + 1) = x · y + x (times successor) number theory that are not T PA -valid. Line 3 is an axiom schema. The reason: T PA actually admits nonstandard interpretations Example: 3 x + 5 = 2 y can be written using Σ PA as Satisfiability and validity in T PA is undecidable. Restricted theory – no multiplication x + x + x + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = y + y 3- 7 3- 8

2. Presburger Arithmetic T N 3. Theory of Integers T Z Σ N : { 0 , 1 , + , = } no multiplication! Σ Z : { . . . , − 2 , − 1 , 0 , 1 , 2 , . . . , − 3 · , − 2 · , 2 · , 3 · , . . . , + , − , = , > } where Axioms T N : ◮ . . . , − 2 , − 1 , 0 , 1 , 2 , . . . are constants 1. ∀ x . ¬ ( x + 1 = 0) (zero) ◮ . . . , − 3 · , − 2 · , 2 · , 3 · , . . . are unary functions 2. ∀ x , y . x + 1 = y + 1 → x = y (successor) (intended 2 · x is 2 x ) 3. F [0] ∧ ( ∀ x . F [ x ] → F [ x + 1]) → ∀ x . F [ x ] (induction) ◮ + , − , = , > 4. ∀ x . x + 0 = x (plus zero) T Z and T N have the same expressiveness 5. ∀ x , y . x + ( y + 1) = ( x + y ) + 1 (plus successor) 3 is an axiom schema. • Every T Z -formula can be reduced to Σ N -formula. Example: Consider the T Z -formula T N -satisfiability and T N -validity are decidable F 0 : ∀ w , x . ∃ y , z . x + 2 y − z − 13 > − 3 w + 5 (Presburger, 1929) Introduce two variables, v p and v n (range over the nonnegative integers) for each variable v (range over the integers) of F 0 3- 9 3- 10 • Every T N -formula can be reduced to Σ Z -formula. Example: To decide the T N -validity of the T N -formula ∀ w p , w n , x p , x n . ∃ y p , y n , z p , z n . F 1 : ( x p − x n ) + 2( y p − y n ) − ( z p − z n ) − 13 > − 3( w p − w n ) + 5 ∀ x . ∃ y . x = y + 1 Eliminate − by moving to the other side of > decide the T Z -validity of the T Z -formula ∀ w p , w n , x p , x n . ∃ y p , y n , z p , z n . ∀ x . x ≥ 0 → ∃ y . y ≥ 0 ∧ x = y + 1 , F 2 : x p + 2 y p + z n + 3 w p > x n + 2 y n + z p + 13 + 3 w n + 5 where t 1 ≥ t 2 expands to t 1 = t 2 ∨ t 1 > t 2 Eliminate > T Z -satisfiability and T N -validity is decidable ∀ w p , w n , x p , x n . ∃ y p , y n , z p , z n . ∃ u . ¬ ( u = 0) ∧ x p + y p + y p + z n + w p + w p + w p F 3 : = x n + y n + y n + z p + w n + w n + w n + u +1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 +1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 . which is a T N -formula equivalent to F 0 . 3- 11 3- 12

Rationals and Reals 1. Theory of Reals T R Σ = { 0 , 1 , + , − , = , ≥} Σ R : { 0 , 1 , + , − , · , = , ≥} with multiplication. ◮ Theory of Reals T R (with multiplication) Axioms in text. √ x 2 = 2 ⇒ x = ± 2 Example: ◮ Theory of Rationals T Q (no multiplication) ∀ a , b , c . b 2 − 4 ac ≥ 0 ↔ ∃ x . ax 2 + bx + c = 0 x = 2 is T R -valid. 2 x = 7 ⇒ 7 ���� x + x T R is decidable (Tarski, 1930) High time complexity Note: Strict inequality OK ∀ x , y . ∃ z . x + y > z rewrite as ∀ x , y . ∃ z . ¬ ( x + y = z ) ∧ x + y ≥ z 3- 13 3- 14 Recursive Data Structures (RDS) 2. Theory of Rationals T Q Σ Q : { 0 , 1 , + , − , = , ≥} 1. RDS theory of LISP-like lists, T cons without multiplication. Σ cons : { cons , car , cdr , atom , = } Axioms in text. where Rational coefficients are simple to express in T Q cons( a , b ) – list constructed by concatenating a and b car( x ) – left projector of x : car(cons( a , b )) = a Example: Rewrite cdr( x ) – right projector of x : cdr(cons( a , b )) = b 2 x + 2 1 3 y ≥ 4 atom( x ) – true iff x is a single-element list as the Σ Q -formula Axioms: 3 x + 4 y ≥ 24 1. The axioms of reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity of = 2. Congruence axioms T Q is decidable Quantifier-free fragment of T Q is efficiently decidable ∀ x 1 , x 2 , y 1 , y 2 . x 1 = x 2 ∧ y 1 = y 2 → cons( x 1 , y 1 ) = cons( x 2 , y 2 ) ∀ x , y . x = y → car( x ) = car( y ) ∀ x , y . x = y → cdr( x ) = cdr( y ) 3- 15 3- 16

Recommend

More recommend