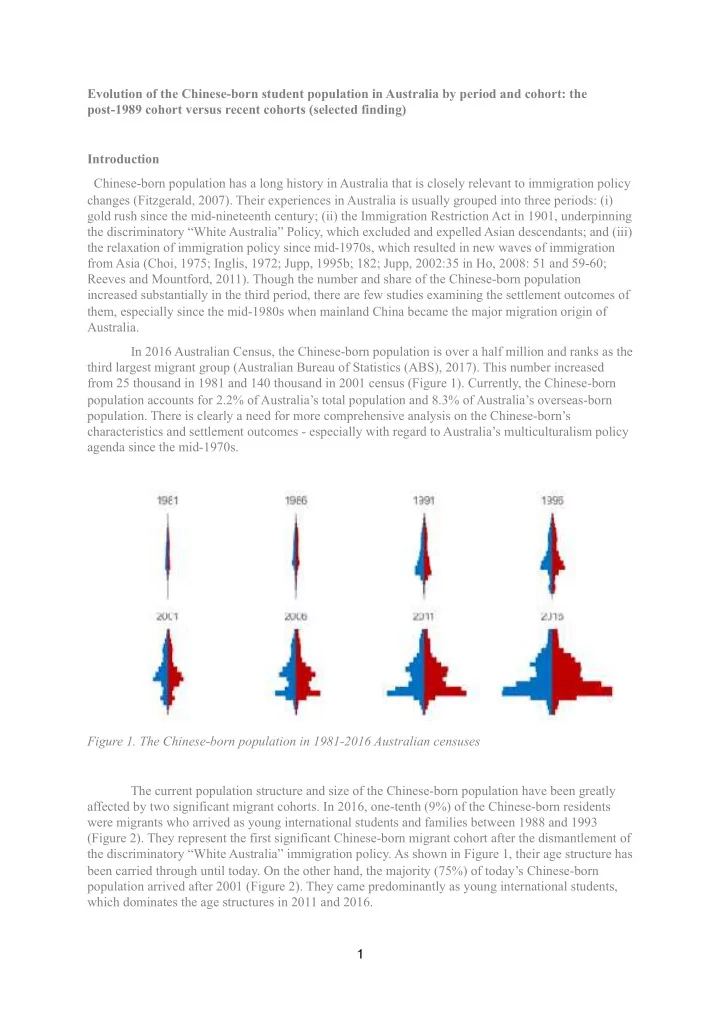

� Evolution of the Chinese-born student population in Australia by period and cohort: the post-1989 cohort versus recent cohorts (selected finding) Introduction Chinese-born population has a long history in Australia that is closely relevant to immigration policy changes (Fitzgerald, 2007). Their experiences in Australia is usually grouped into three periods: (i) gold rush since the mid-nineteenth century; (ii) the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, underpinning the discriminatory “White Australia” Policy, which excluded and expelled Asian descendants; and (iii) the relaxation of immigration policy since mid-1970s, which resulted in new waves of immigration from Asia (Choi, 1975; Inglis, 1972; Jupp, 1995b; 182; Jupp, 2002:35 in Ho, 2008: 51 and 59-60; Reeves and Mountford, 2011). Though the number and share of the Chinese-born population increased substantially in the third period, there are few studies examining the settlement outcomes of them, especially since the mid-1980s when mainland China became the major migration origin of Australia. In 2016 Australian Census, the Chinese-born population is over a half million and ranks as the third largest migrant group (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2017). This number increased from 25 thousand in 1981 and 140 thousand in 2001 census (Figure 1). Currently, the Chinese-born population accounts for 2.2% of Australia’s total population and 8.3% of Australia’s overseas-born population. There is clearly a need for more comprehensive analysis on the Chinese-born’s characteristics and settlement outcomes - especially with regard to Australia’s multiculturalism policy agenda since the mid-1970s. Figure 1. The Chinese-born population in 1981-2016 Australian censuses The current population structure and size of the Chinese-born population have been greatly affected by two significant migrant cohorts. In 2016, one-tenth (9%) of the Chinese-born residents were migrants who arrived as young international students and families between 1988 and 1993 (Figure 2). They represent the first significant Chinese-born migrant cohort after the dismantlement of the discriminatory “White Australia” immigration policy. As shown in Figure 1, their age structure has been carried through until today. On the other hand, the majority (75%) of today’s Chinese-born population arrived after 2001 (Figure 2). They came predominantly as young international students, which dominates the age structures in 2011 and 2016. 1

� Figure 2. The Chinese-born population in 2016 Australian census: by period of arrival Various studies suggest that the settlement behaviour and outcomes of migrants differ by age, birth cohort and migrant cohort (or migration period) (e.g. Pandit, 1997; Coughlan, 2008; Sander and Bell, 2016). However, few studies address the variations in permanent settlement behaviours and outcomes across different migrant cohorts of the Chinese-born. More specifically, there are only a handful of literature on the students who were affected by Tiananmen Incident-related immigration policies: not only in Australia where there were around 30,000, but also in the United States where the number was 53,000 (Birrell, 1994; Shu and Hawthorne 1996; Gao and Liu, 1998; Hugo, 2008; Orrenius et al., 2012). To understand the intra-birthplace variations, especially the settlement of the students who were affected by Tiananmen Incident-related policies and recent international students who became permanent residents in Australia, this study will compare the demographic, socio-economic and residential patterns of 1988-93 arrivals and 2001-06 arrivals. Using information from the Settlement Database, the two migrant cohorts are further narrowed down with age on arrival and education level to capture main characteristics of those international students who became permanents residents later on. The study explores how a major international migration flow from China to Australia evolved over time in response to political events, immigration or international student policies at both sides. Other than examine international migration as a population redistribution process, this study investigates migration as a life course event by comparing migrants’ settlement outcomes over age, birth cohort and migrant cohort. There is an extensive literature investigating fertility patterns of immigrants in Australia, though little emphasis has been given to the Chinese-born. During 1977-1991, Chinese-born female immigrants, resembling migrants from many other non-English-speaking Asian countries, experienced considerably lower fertility in Australia than did the population in mainland China (Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald, 2000: Figure 1). Aside from analysis on census variables, multistate life tables are constructed for different birth cohorts and migration periods to better understand the geographic movements and life course pathways. The spatial distributions of Chines-born population, in particular the urban-rural concentration and state level disparities, has been of great concern since the early migration period (Huck, 1968: 11-12; Inglis, 1972; Choi, 1975: 67-77 and Table 2.3; Kee and Huck, 1991; Jupp, 1995a; Ho and Coughlan, 1997: Table 6.6-6.9; Coughlan, 2008a and 2008b; Reeves and Mountford, 2011). Limited by data and techniques, it remains unclear in the existing literature what has been the pathway of migrants’ spatial movement, and how that differed between migrant cohorts. 2

RESEARCH QUESTIONS The study answers the following questions: 1. How have the demographic profiles, including age-sex structures, marriage and fertility changed between 1989-93 and 2006-11 Chinese-born student-to-permanent resident populations in Australia? 2. How do the settlement outcomes, including socio-economic status and spatial movement patterns changed between 1989-93 and 2006-11 Chinese-born student-to-permanent resident populations in Australia? DATA AND METHODOLOGY Data of this study comes from two sources. First is the Settlement Database, an administrative database of permanent visa recipients. Second is Australian census data for year 2006, 2011, and 2016. The Settlement Database collects data on immigrants who received permanent visa or settlement pathway temporary visa after 1991. It is managed by the Department of Social Services and only records information from immigrants’ most current visa if they had not updated any status change ever since. Data items of the Settlement Database provides some useful information on migration history: for instance, country of birth, age on arrival, year of arrival, year of education, and visa subclass. Therefore it is a good source to identify the characteristics of the migrant cohort who was affected by Tiananmen Incident-related Australian immigration policy using the visa subclass information. The dataset is used to narrow the two migrant cohorts down using year of arrival, age on arrival and education level information to define the student-to-permanent resident population. However, because of the inconsistency on data updating, the Settlement Dataset is not a suitable source for comparative analysis over birth cohort and migrant cohort. Australian censuses are conducted every five years and represents one of the most comprehensive data sources on the overseas-born population. The proportion of Chinese-born population is 1.0% in 2006 census, 1.8% in 2011 census and 2.2% in 2016 census. These three most recent censuses are made publicly available online with the option to cross-tabulate most of the census data items. Using year of arrival, age at the census and education level variables, main characteristics of the 1988-93 and 2001-06 student-to-permanent resident cohorts can be captured in each of the three censuses. To compare the demographic, socio-economic and spatial patterns of the two migrant cohorts over the three censuses, variables including marital status, number of children ever born, citizenship, religious affiliation, language spoken at home, English language proficiency, labour force status, weekly income, and usual residence changes are collected from the census online tool TableBuilder. The study cross-tabulates census data to analyse family formation, fertility level, political and social integration of the two migrant cohort. To capture the Chinese students affected by Tiananmen Incident, the two migrant cohorts in the census are further narrowed down to two student-to- permanent resident cohorts by age on arrival (18-44) and education level (at least year 12). The age and education constrains are based on Settlement Database statistics. In the Settlement Database, the 1988-93 cohort is predominantly humanitarian visa recipients (71.8%) while the 2001-06 is mainly skilled visa recipients (67.1%). Further disaggregating the 1988-93 cohort humanitarian visa recipients by visa subclass, the majority of them are 815, 816, 817 and 818 visa recipients (90%). These visas were granted after 1993 mainly to mainland Chinese students and their families who arrived Australia in late 1980s and early 1990s in response to the 1989 Tiananmen Incident in Beijing (Ju Liu Sui Yue, 2014). Overall, 90% of the Chinese-born 815-818 visa recipients arrived Australia between 1988 and 1993. Of them, 83% of were aged 18-44 on arrival and 3

Recommend

More recommend