Evidence in Class Actions Lessons From Recent Cases on the Use of - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

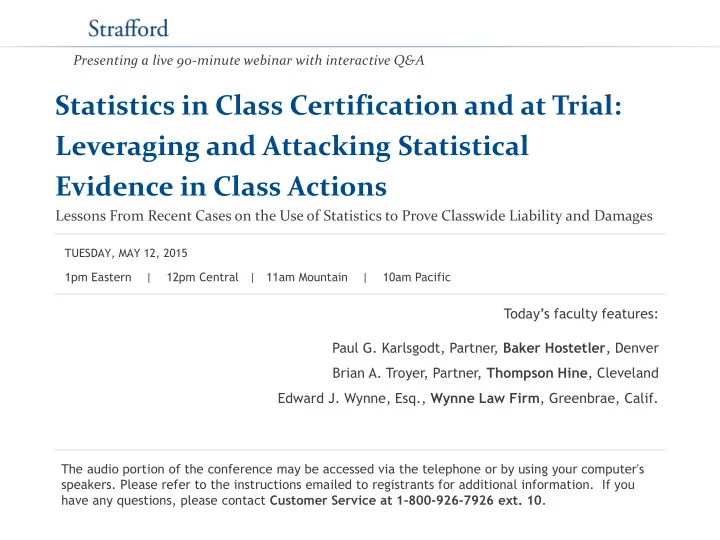

Presenting a live 90-minute webinar with interactive Q&A Statistics in Class Certification and at Trial: Leveraging and Attacking Statistical Evidence in Class Actions Lessons From Recent Cases on the Use of Statistics to Prove Classwide

Presenting a live 90-minute webinar with interactive Q&A Statistics in Class Certification and at Trial: Leveraging and Attacking Statistical Evidence in Class Actions Lessons From Recent Cases on the Use of Statistics to Prove Classwide Liability and Damages TUESDAY, MAY 12, 2015 1pm Eastern | 12pm Central | 11am Mountain | 10am Pacific Today’s faculty features: Paul G. Karlsgodt, Partner, Baker Hostetler , Denver Brian A. Troyer, Partner, Thompson Hine , Cleveland Edward J. Wynne, Esq., Wynne Law Firm , Greenbrae, Calif. The audio portion of the conference may be accessed via the telephone or by using your computer's speakers. Please refer to the instructions emailed to registrants for additional information. If you have any questions, please contact Customer Service at 1-800-926-7926 ext. 10 .

Tips for Optimal Quality FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY Sound Quality If you are listening via your computer speakers, please note that the quality of your sound will vary depending on the speed and quality of your internet connection. If the sound quality is not satisfactory, you may listen via the phone: dial 1-866-869-6667 and enter your PIN when prompted. Otherwise, please send us a chat or e-mail sound@straffordpub.com immediately so we can address the problem. If you dialed in and have any difficulties during the call, press *0 for assistance. Viewing Quality To maximize your screen, press the F11 key on your keyboard. To exit full screen, press the F11 key again.

Continuing Education Credits FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY For CLE purposes, please let us know how many people are listening at your location by completing each of the following steps: In the chat box, type (1) your company name and (2) the number of • attendees at your location Click the SEND button beside the box • In order for us to process your CLE, you must confirm your participation by completing and submitting an Official Record of Attendance (CLE Form) to Strafford within 10 days following the program. The CLE form is included in your dial in instructions email and in a thank you email that you will receive at the end of this program. Strafford will send your CLE credit confirmation within approximately 30 days of receiving the completed CLE form. For additional information about CLE credit processing call us at 1-800-926-7926 ext. 35.

Program Materials FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY If you have not printed the conference materials for this program, please complete the following steps: Click on the ^ symbol next to “Conference Materials” in the middle of the left - • hand column on your screen. • Click on the tab labeled “Handouts” that appears, and there you will see a PDF of the slides for today's program. • Double click on the PDF and a separate page will open. Print the slides by clicking on the printer icon. •

“Conceptual Gaps” and Related Problems: Understanding and Challenging Statistical Evidence in Class Actions Brian Troyer Brian.Troyer@ThompsonHine.com

Two Contrasting Uses of “Representative” • In statistics, a representative sample is one from which population characteristics can be inferred. – Representative sample: random selection, sufficient size, population characteristics – Population statistics, including those calculated from samples, support only predictions or estimates about any individual class member or other unit of analysis. • Under Rule 23, a representative plaintiff must “possess the same interest and share the same injury .” Wal-Mart Stores Inc. v. Dukes , 131 S. Ct. 2541 (2011). – In a class action, it must be possible to draw conclusions about individuals . The theory of a class action is that it is fair to draw conclusions because the evidence in the plaintiff’s individual case is the same evidence that would be used in other class member’s cases. Under Rule 23, evidence is representative because it is the same evidence for each class member. • What evidence would be used in the plaintiff’s individual case (or another’s)? • Would the evidence in each class members’ case consist of that same evidence? • Is statistical evidence being offered only to justify class treatment, or would the named plaintiff use that evidence? – Aggregate or composite proof is not the same as representative proof, nor is a mere sample of aggregate proof. The important question is whether there is different evidence, not whether there is any similar evidence.

Ecological Fallacy • This type of fallacy occurs when a conclusion is drawn about an individual from analysis of group data. Population statistics do not permit such conclusions. – If seniors at Smart University have a mean LSAT score 5 points above the national average, we cannot conclude that Joe’s score is 5 points above it. Even with additional statistics like distribution and standard deviation calculations, we can only obtain probabilities or estimates about individuals. • Ecological fallacies are prevalent in many kinds of class actions when statistics are offered as common proof of conduct, impact, or damages, and population characteristics are imputed to each individual member of a class or other individual unit of analysis. – If women on average were less likely to be promoted or given raises, Jane Doe suffered discrimination (or there is a common question of discrimination). – If X% of promotion decisions were discriminatory, Jane Doe suffered X such acts of discrimination. – If employees on average worked 2 hours per week overtime, John Doe was denied overtime pay. – If employees worked on average more than 50% in the office, John Doe worked more than 50% in the office and was non-exempt. – If 75% of widgets are 10% out of tolerance, Joe’s widget is 10% out of tolerance. – If ABC product contained on average more than 50% ingredient A, and it should contain 50% or less, there is a common question of whether ABC product is defective.

Statistics and The Illusion of Commonality • Statistics often show only an illusory form of commonality. An inference that 51% of a population is affected by a practice • disproves rather than supports a finding of commonality; • leaves unanswered which individuals within the population were affected. • Statistical probabilities cannot supplant direct, individual proof and do not establish commonality ( differences matter). – How would we ascertain Joe’s actual LSAT score if it was important to know? Look at the score. • Practice pointer: plaintiffs’ use of statistics or aggregate evidence cannot properly deprive a defendant of the right to discover and use individual evidence.

Additional Conceptual and Technical Issues • Erroneous or unsupported assumptions – All off-label marketing is fraudulent ( i.e., off-label use is ineffective). – All class members were unaware the drug was unapproved. • Statistical measures without reference to any objective standard – Standard deviation without reference to magnitude of permissible deviation – No objective standards of value similarity or correspondence – No objective definitions of product or performance characteristics or requirements underlying calculation • Misapplication or misuse of statistical measures – Standard deviations and/or averages used to portray uniformity or consistency • Averages by their nature conceal variations. • Standard deviations do not account for all cases.

Additional Conceptual and Technical Issues • Correlations that depend upon arbitrary scales – Data/variables placed on a scale from 0-100% in arbitrary percentage ranges may exhibit correlations dependent upon how the scale is divided. • Correlations and trends that are artifacts of arbitrary data aggregation and averaging, concealing individual variables and confounding effects – In re Graphics Processing Units Antitrust Litig., 253 F.R.D. 478 (N.D. Cal. July 18, 2008) (false correlations created by averaging price changes across products, purchasers, and channels). – Simpson’s Paradox (trend or correlation reverses with combination or separation of data sets) • Implicit statistical inferences denied to be subject to rules of statistics – Testing a handful out of millions of specimens and drawing conclusions as to all – Selection of “representative” plaintiffs or cases based upon expert judgment (purposive sampling), or improper extrapolation by “subject matter expert”

Additional Conceptual and Technical Issues • Data collected for different purposes and without accounting for critical variables – Were the necessary parameters properly measured or counted? – Double counting, miscounting? – Do the data sources reflect different population subsets or assumptions? • Sampling from the dependent variable (or no true independent variable), but extrapolation of inferences to all – Statistical analyses only of defective product units – Measurement of injury rate only among those known to have actual exposure – Comparison of extent of damage to extent of exposure only in damaged units

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.