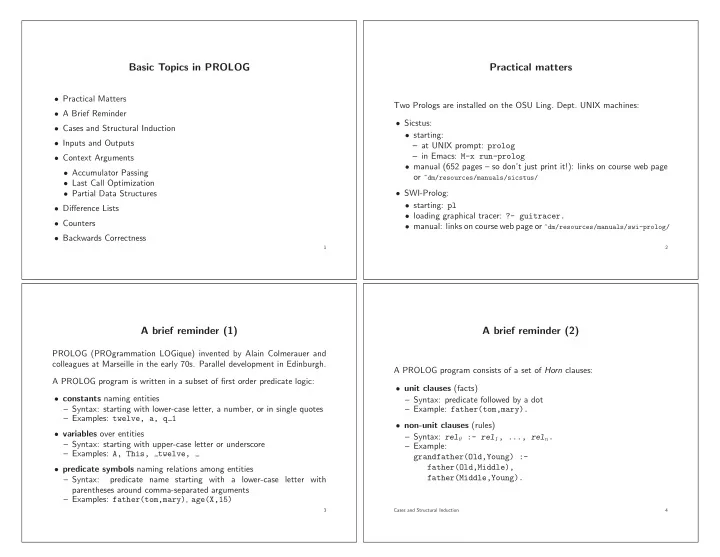

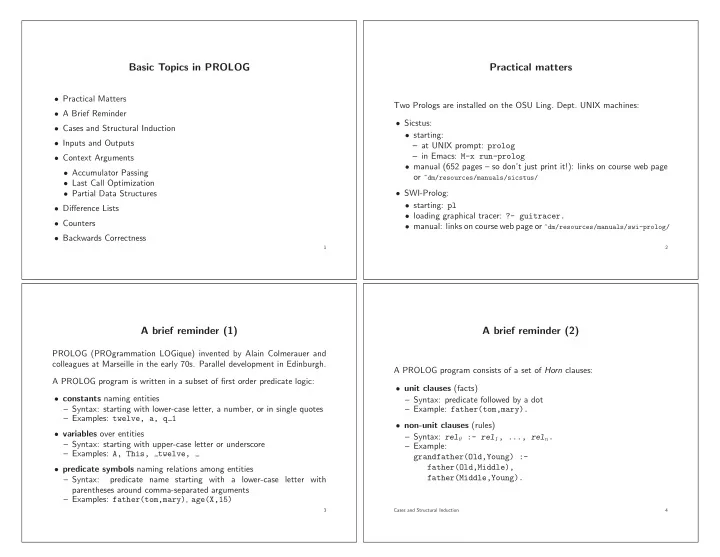

Basic Topics in PROLOG Practical matters • Practical Matters Two Prologs are installed on the OSU Ling. Dept. UNIX machines: • A Brief Reminder • Sicstus: • Cases and Structural Induction • starting: • Inputs and Outputs – at UNIX prompt: prolog – in Emacs: M-x run-prolog • Context Arguments • manual (652 pages – so don’t just print it!): links on course web page • Accumulator Passing or ~dm/resources/manuals/sicstus/ • Last Call Optimization • Partial Data Structures • SWI-Prolog: • starting: pl • Difference Lists • loading graphical tracer: ?- guitracer. • Counters • manual: links on course web page or ~dm/resources/manuals/swi-prolog/ • Backwards Correctness 1 2 A brief reminder (1) A brief reminder (2) PROLOG (PROgrammation LOGique) invented by Alain Colmerauer and colleagues at Marseille in the early 70s. Parallel development in Edinburgh. A PROLOG program consists of a set of Horn clauses: A PROLOG program is written in a subset of first order predicate logic: • unit clauses (facts) • constants naming entities – Syntax: predicate followed by a dot – Syntax: starting with lower-case letter, a number, or in single quotes – Example: father(tom,mary). – Examples: twelve, a, q 1 • non-unit clauses (rules) • variables over entities – Syntax: rel 0 :- rel 1 , ..., rel n . – Syntax: starting with upper-case letter or underscore – Example: – Examples: A, This, twelve, grandfather(Old,Young) :- father(Old,Middle), • predicate symbols naming relations among entities father(Middle,Young). – Syntax: predicate name starting with a lower-case letter with parentheses around comma-separated arguments – Examples: father(tom,mary) , age(X,15) 3 Cases and Structural Induction 4

Basic use of arguments: Discriminate between cases Compound terms as data structure for recursive relations To define (interesting) recursive relations, one needs a richer data structure direction_adjective(north, boreal). than the constants used so far: compound terms . direction_adjective(south, austral). direction_adjective(east, oriental). direction_adjective(west, occidental). • A compound term comprises a functor and a sequence of one or more terms, the argument. Atoms can be thought of as functors with arity 0. abs_diff(X, Y, Diff) :- • Compound terms are standardly written in prefix notation. compare(R, X, Y), Example: bin tree(s, np, bin tree(vp,v,n)) abs_diff(R, X, Y, Diff). abs_diff(<,X,Y,Diff) :- Diff is Y-X. Infix and postfix operators can also be defined, but need to be declared abs_diff(>,X,Y,Diff) :- Diff is X-Y. using op/3 . abs_diff(=,_,_,0). Cases and Structural Induction 5 Cases and Structural Induction 6 Lists as special compound terms Four equivalent representations: Lists are represented as compound terms. • empty list: represented by the atom “ [] ” . 1. .(a, .(b, .(c, .(d,[])))) 4. • non-empty lists: symbol ” . ” as binary functor .( first , rest ) a . Example: .(a, .(b, .(c, .(d,[])))) b . Special notations: 2. [a | [b | [c | [d | []]]]] c . • [ element1 | restlist ] Example: [a | [b | [c | [d | []]]]] d [] 3. [a,b,c,d] • [ element1 , element2 ] = [ element1 | [ element2 | []]] Example: [a, b, c, d] Cases and Structural Induction 7 Cases and Structural Induction 8

Structural induction arithmetic_value(-F, Value) :- % b2) recursive case arithmetic_value(F,Fval), Value is -Fval. is_list([]). % a) base/non-recursive case arithmetic_value(E-F, Value) :- % b3) recursive case is_list([_|Tail]) :- % b) step/recursive/inductive case arithmetic_value(E,Eval), is_list(Tail). arithmetic_value(F,Fval), Value is Eval - Fval. arithmetic_value(E*F, Value) :- % b4) recursive case % arithmetic_value(Expr,Value) arithmetic_value(E,Eval), % is true when Expr represents an arithmetic expression and arithmetic_value(F,Fval), % Value is its numeric value Value is Eval * Fval. arithmetic_value(E/F, Value) :- % b5) recursive case arithmetic_value(c(N), N). % a) base case arithmetic_value(E,Eval), arithmetic_value(E+F, Value) :- % b1) recursive case arithmetic_value(F,Fval), arithmetic_value(E,Eval), Value is Eval / Fval. arithmetic_value(F,Fval), Value is Eval + Fval. Cases and Structural Induction 9 Cases and Structural Induction 10 Why is this called structural induction ? A closer look at arguments: Inputs and Outputs • induction : defined recursively • structural : recursion controlled by structure, not contents In principle, any argument (or part of it) can be input or output: birthday(byron, date(feb,4)). Two things to watch out for: birthday(noelene, date(dec,25)). birthday(richard, date(oct,11)). • missing cases birthday(clare, date(sep,15)). • duplicate cases An example for intentional duplicate cases: ?- birthday(byron,Date). member(X,[X|_]). ?- birthday(Person, date(feb,4)). member(X,[_|L]) :- member(X,L). ?- birthday(Person, date(feb,Day)). Inputs and Outputs 11 Inputs and Outputs 12

Predicates solving for particular arguments only Multiple output arguments Built-in predicates involving arithmetic expressions no output argument (true/false) • Expression must be ground in evaluation of Answer is Expression greater_than(X,Y) :- X < Y. (expression has one value, but same value for infinitely many expressions) • Both arguments must be ground in comparisons: E<F , E>F , E>=F , . . . one output argument: min Predicates using these built-ins have specific inputs and outputs: min(X, Y, X) :- X < Y. factorial(0,1). min(X, Y, Y) :- X >= Y. factorial(N,N_Factorial) :- N > 0, two output arguments: min, max M is N-1, factorial(M, M_Factorial), min_and_max(X, Y, X, Y) :- X < Y. N_Factorial is M_Factorial*N. min_and_max(X, Y, Y, X) :- X >= Y. Recursive predicates often require particular arguments to terminate. Inputs and Outputs 13 Inputs and Outputs 14 Order of arguments Templates and meta-arguments Template: Why a uniform ordering? • Pattern for making/selecting things. • clarity: consistency makes programs easier to understand • Example: first argument of findall/3 • efficiency: first argument indexing ?- findall(Month-Day, birthday(_Name,date(Month,Day)), Bag). Bag = [feb-4,dec-25,oct-11,sep-15] Suggested ordering • General rule: strict inputs < inputs-or-outputs < strict outputs Meta-Argument: • Among strict inputs: templates < meta-arguments < streams < • Term which stands for a goal. selectors/indices < collections < other strict inputs • Example: argument of call/1 or second argument of findall/3 Inputs and Outputs 15 Inputs and Outputs 16

Streams Selectors/Indices and Collections Selectors/Indices: • Terms representing open files • Terms which function like array subscripts. • Example: third argument of open/3 • Example: first argument of arg/3 file_write :- ?- arg(3,p(a(n,o),b,c(m),d),X). open(myfile,write,MyStream), % modes: read/write/append X = c(m) write(MyStream,’output to file’), write(’output to screen (standard output)’), ?- functor(p(a(n,o),b,c(m),d),Functor,Arity). close(MyStream). Arity = 4, Functor = p % simple case not using explicit streams simple_file_write :- Collections: tell(myfile), • essentially every compound term can be used as a collection write(’output to file’), • Example: second argument of arg/3 told. Inputs and Outputs 17 Inputs and Outputs 18 Other ordering guidelines The scope of variables • sequence order: keep abstract sequences together (difference lists, accumulator pairs. . . ) • There are no non-local variables in Prolog. • code/data consistency: e.g., Head < Tail since [Head|Tail] • Non-local variables are encoded as extra arguments of a predicate which are passed unchanged into the recursion. • function direction: most general input first Example: Term =.. List % scale(SmallList,Multiplier,BigList) (every Term corresponds to a List , but not vice versa) % True if each element of SmallList multiplied by Multiplier ?- p(a(n,o),b,c(m),d) =.. List. % is equal to the corresponding element of BigList. X = [p,a(n,o),b,c(m),d] scale([], _, []). ?- Term =.. [1,a(n,o),b,c(m),d]. scale([X|Xs], Multiplier, [Y|Ys]) :- {TYPE ERROR: _169=..[1,a(n,o),b,c(m),d] - Y is X*Multiplier, arg 2: expected atom, found 1} scale(Xs, Multiplier, Ys). Inputs and Outputs 19 Context Arguments: global variables as context 20

Packaging contexts % big_elements(FullList,SubList) % True if SubList is the list of those elements of % FullList which are bigger than 10, preserving order. context(conx(A,B,C,D),A,B,C,D). big_elements(Input,Output) :- big_elements(Input, 10, Output). context_a(conx(A,_,_,_),A). context_b(conx(_,B,_,_),B). big_elements([], _, []). context_c(conx(_,_,C,_),C). big_elements([Nbr|Nbrs], Bound, Bigs) :- context_d(conx(_,_,_,D),D). Nbr < Bound, big_elements(Nbrs, Bound, Bigs). c(...) :- big_elements([Nbr|Nbrs], Bound, [Nbr|Bigs]) :- init(...,A,B,C,D,...), Nbr >= Bound, context(Context,A,B,C,D), big_elements(Nbrs, Bound, Bigs). p(...,Context,...), ... Context Arguments: global variables as context 21 Context Arguments: global variables as context 22 p(...,Context,...) :- Accumulator passing ... context_a(Context,A), use_a(A), • There is no changing of variable values in Prolog. ... p(...,Context,...). • Two variables are used to store old and new value ( accumulator passing ). p(...,Context,...) :- ... len(List,Length) :- context_b(Context,B), len(List, 0, Length). use_b(B), ... len([], N, N). p(...,Context,...). len([_|L], N0, N) :- N1 is N0+1, len(L, N1, N). Context Arguments: global variables as context 23 Context Arguments: changing values as accumulator passing 24

Recommend

More recommend