and conflict-affected settings: from research to practice Webinar: - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected settings: from research to practice Webinar: Hosted by the HSG Thematic Working Group on Health Systems in Fragile and Conflict Affected States 31 st October 2018 Housekeeping rules

Performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected settings: from research to practice Webinar: Hosted by the HSG Thematic Working Group on Health Systems in Fragile and Conflict Affected States 31 st October 2018

Housekeeping rules Please keep your microphones muted We will not be using webcams Please submit your questions through the Questions Box For technical support please write to n.jalaghonia@curatio.com

Performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected settings: from research to practice Introduction: Professor Sophie Witter IGHD, Queen Margaret University & ReBUILD

Why the FCAS focus? • Two billion people now live in situations affected by fragility and conflict (World Bank 2018) • Share of extreme poor living in conflict-affected situations is expected to rise to 80% by 2030 if not action is taken • Conflict and population displacement now at highest level for 30 years • More than 60% of maternal and child deaths occur in FCAS (OECD 2018) • A recent study found that armed conflict substantially and persistently increases infant mortality in Africa (Wagner et al., 2018) • However, fragile states receive around 50% less aid than predicted , despite their high needs (Graves et al., 2015), also less health research • In this context, making progress towards universal health coverage (UHC) and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is particularly challenging

ReBUILD Decisions made early post-conflict/post-crisis can steer the long term development of the health system Consortium partners (2011-18) Opportunity Post conflict is a • College of Medicine and Allied Health to set health Sciences (CoMAHS), Sierra Leone neglected area systems in a • Biomedical Training and Research Institute of health (BRTI), Zimbabwe pro-poor system research • Makerere University School of Public direction Health (MaKSPH), Uganda • Cambodia Development Research Institute (CDRI) Choice of Useful to think • Institute for International Health and focal about what Development (IIHD), Queen Margaret University, UK policy space countries • Liverpool school of Tropical Medicine (UK) there is in the enable distance Consortium affiliates working in additional immediate and close up countries: Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria and South Africa; Sri Lanka, Gaza and Liberia post-conflict view of post period conflict Extended work in second phase in northern Nigeria, CAR, DRC, Timor Leste

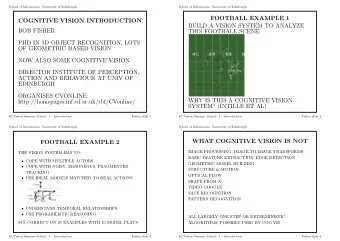

Why focus on PBF? • Many different forms and terminology within the RBF school • PBF aims to improve health services by providing payments to service providers (usually facilities, but often with a portion paid to individual staff) based on the verified quantity of outputs produced, modified by quality indicators. – In many cases there is a division of functions between regulation, purchasing, fund-holding, and service delivery • It has expanded rapidly across low and middle countries, over the last decade, and especially in FCAS settings, but relatively little work on how context affects PBF – Conflicting arguments: some argue that PBF is unlikely to be effective in fragile settings while others point out that precisely in situations of weak institutions there is more potential for PBF to re-align relationships and improve accountability

PBF in sub-Saharan Africa Source : Fritsche et al., 2014

Patterns of PBF adoption in FCAS – 23 (43%) out of 53 FCAS countries have/had at least one PBF programme – 19 (56%) out of 34 PBF programmes in SSA are implemented in FCAS Afghanistan Comoros Guinea Nigeria Burundi Congo (Republic) Guinea Bissau Rwanda Cambodia Cote d’Ivoire Haiti Sierra Leone Cameroon Djibouti Lao PDR Tajikistan Central African DR Congo Liberia Zimbabwe Republic Chad The Gambia Mali Bertone, M., Falisse, J-B., Russo, G., Witter, S. (2018) Context matters (but how and why?) A hypothesis-led literature review of performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected health systems. PLOS ONE, 13(4): e0195301.

PBF adoption over time – All PBF programmes in SSA implemented before 2006 are in FCAS settings (Rwanda , Burundi, DRC, Cameroon, Cote d’ Ivoire) – The first countries to have scaled-up PBF nationwide are also FCAS: Rwanda (2008), Burundi (2010) and Sierra Leone (2011) – Appears to have been a successor to PBC model supported earlier by donors in FCAS (Cambodia, Haiti, Afghanistan and Liberia) – Often multiple schemes – e.g. DRC (7) and Burundi (6) over past ten years

Why was PBF introduced? Link with experience of conflict and fragility rarely explicitly made PBF facilitating factors – some hypotheses confirmed: – Low levels of interpersonal trust and need to strengthen accountability and good governance (Mali, Burundi, Cameroon) – Lack of trust between donors and government and fiduciary concerns (DRC, Cote d ’ Ivoire, Zimbabwe) – Flexibility (or absence) of existing institutions (Rwanda, Burundi) – Less entrenched interests and power relations (SL) – Push for decentralisation and facility autonomy? Often de facto (inherited from conflict period) and not explicitly acknowledged, although present

Features of implementation – hypotheses & evidence More variation and adaptation of PBF in FCAS? → Copy-and-paste approaches after first scheme in Rwanda → Exception: adaptation to humanitarian and early recovery contexts (Nigeria, CAR, Cameroon, SL) Challenges sustaining PBF overtime → start-stop(-start) approaches (SL, Chad) → More sustainable when linked to broader health financing/system reforms (Rwanda, Burundi)

Components of our PBF work 1. Hypothesis-driven literature review : How does the context of fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCAS) influence the adoption, adaption, implementation and health system effects of PBF? 2. Political economy of PBF : looking at the dynamics that led to the adoption and expansion of PBF, but also its impact on resource distribution within the health system (Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe) 3. PBF in crises : further explore the emerging adaptations of PBF to humanitarian and early recovery settings (DRC/South Kivu, Nigeria/Adamawa, CAR) 4. Focus on strategic purchasing : as PBF is increasingly considered a potential entry point to strengthen strategic purchasing (and thus the health system), we examined three empirical examples on how PBF has affected the purchasing function (DRC, Uganda, Zimbabwe) https://rebuildconsortium.com/our-research/research-projects/health- financing/performance-based-financing/

Aims for panel • To share key findings of research and reflect together on their relevance • Create dialogue between researchers and practitioners on implications for practice • Shape future research agenda collectively Do please send in your thoughts and questions on these as we talk … .

Our panel Introduction and moderator Prof Sophie Witter (ReBUILD/QMU) 1. The political economy of PBF in fragile settings Dr Maria Bertone (ReBUILD/QMU) Discussant: Noemi Schramm (CHAI, Sierra Leone)

Our panel 2. PBF in humanitarian settings: principles and pragmatism Eelco Jacobs (KIT) Discussant: Piet Vroeg (Consultant, formerly Cordaid) 3. Does PBF strengthen strategic purchasing? The experience of Uganda, Zimbabwe and the DRC Prof Freddie Ssengooba (ReBUILD/Makerere) Discussant: Dr Inke Mathauer (WHO) Discussion

Funded by The political economy of PBF in fragile settings Maria Bertone IGHD, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh ReBUILD Research Consortium ReBUILD is a 6 year £6million research project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID)

Introduction Performance-based financing (PBF) is increasingly implemented in ▪ LMICs, including fragile settings Growing literature on its effects, but less attention to the context and ▪ the processes around PBF adoption and implementation We analyse two case studies: ▪ Sierra Leone (2010-2017): interesting case because of the ‘ start-stop-(start again?) ’ ▪ trajectory Zimbabwe (2011-2018): one of the few nation-wide PBF scheme in SSAfrica ▪

Methods Retrospective, qualitative case studies ▪ Sierra Leone Zimbabwe Document review n=68 n=60 Key informant interviews n=25 n=40 Direct observation √ √ Analytical frameworks drawing from political economy analysis ▪ Actors : roles, interests & agendas, power & influence, ‘ winners & losers ’ ) ▪ Structure : socio-political context, historical legacies, disrupting events, imposed timings ▪ Frames: ideas, meanings, narratives ▪

Timeline PBF in Sierra Leone Low capacity Discussions Salary increase for HWs GAVI on new PBF (HRH TWG+D-HRH) scandal scheme Ebola epidemic 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 PBF Plus FHCI ‘ Simple ’ PBF PBF End of ‘simple’ (1 district) FHCI announ- at primary care level external PBF (now called Pilot by launch cement (start) verif. ‘PBF Light’) Cordaid PBF negotiations Nationwide PBF implementation (WB + DPPI) Externally imposed • timing/ funding Short Little adaptation cycles negotiation Dissonance in • Challenges of Simple PBF process Resourced-strapped environment (aid • • framing (Unsuccessful) attempt to dependency) • shift the narrative Internal divisions w/in MoH • Negotiations moved bilaterally ( venue • shopping )

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.