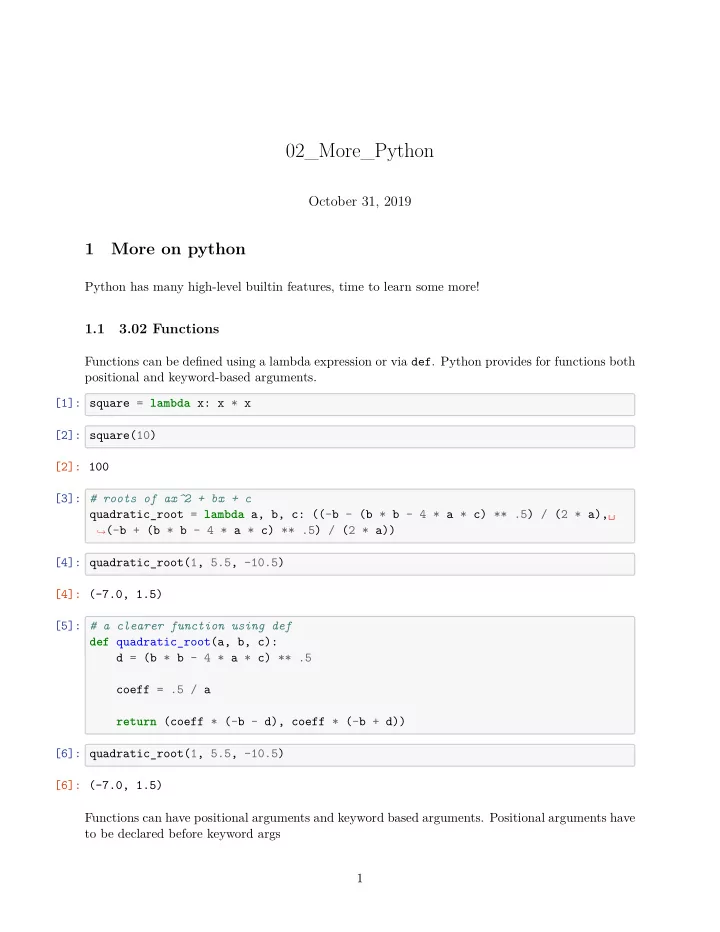

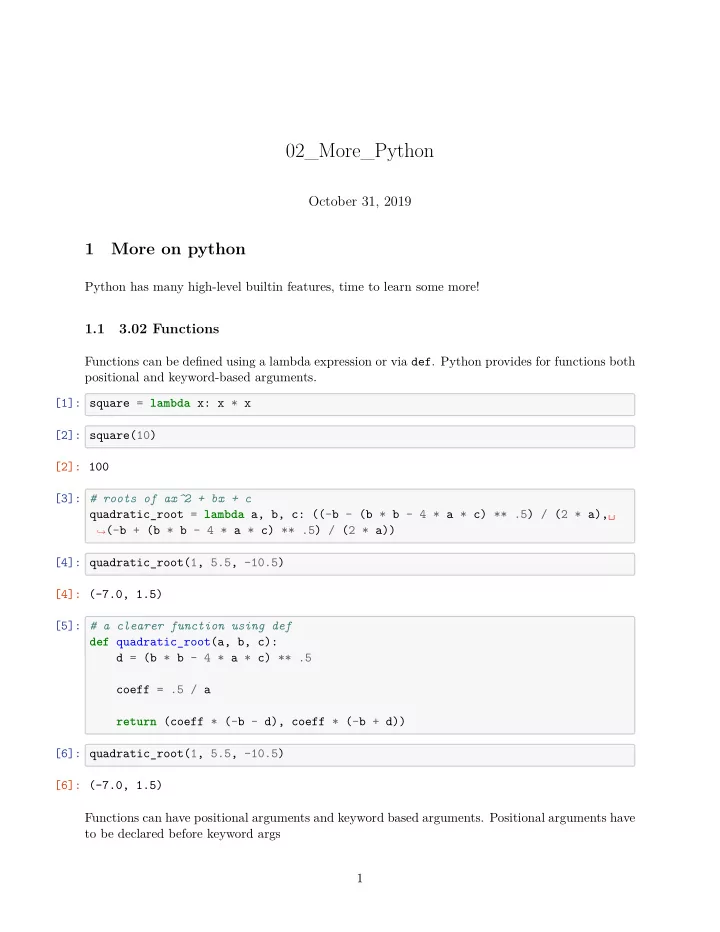

02_More_Python October 31, 2019 to be declared before keyword args Functions can have positional arguments and keyword based arguments. Positional arguments have [6]: (-7.0, 1.5) [6]: quadratic_root(1, 5.5, -10.5) return (coeff * (-b - d), coeff * (-b + d)) coeff = .5 / a def quadratic_root(a, b, c): [5]: # a clearer function using def [4]: (-7.0, 1.5) [4]: quadratic_root(1, 5.5, -10.5) 1 quadratic_root = lambda a, b, c: ((-b - (b * b - 4 * a * c) ** .5) / (2 * a),␣ [3]: # roots of ax^2 + bx + c [2]: 100 [2]: square(10) [1]: square = lambda x: x * x positional and keyword-based arguments. Functions can be defjned using a lambda expression or via def . Python provides for functions both 3.02 Functions 1.1 Python has many high-level builtin features, time to learn some more! More on python 1 ֒ → (-b + (b * b - 4 * a * c) ** .5) / (2 * a)) d = (b * b - 4 * a * c) ** .5

[7]: # name is a positional argument, message a keyword argument SyntaxError: positional argument follows keyword argument [15]: 2.9999999999999996 [15]: log(1000, 10) [14]: 2.302585092994046 [14]: log(10) [13]: 1.0 [13]: log(math.e) return math.log(num) / math.log(base) def log(num, base=math.e): [12]: import math keyword arguments can be used to defjne default values ^ def greet(name, message='Hello {} , how are you today?'): greet(message="Hi {} !", 'Tux') File "<ipython-input-11-0f79efc3a31e>", line 2 greet(message="Hi {} !", 'Tux') [11]: # this doesn't work What's up Tux? [10]: greet('Tux', message='What \' s up {} ?') Hi Tux! [9]: greet('Tux', 'Hi {} !') Hello Tux, how are you today? [8]: greet('Tux') print(message.format(name)) 2

1.2 3.03 builtin functions, attributes [20]: [('brand', 'Ford'), ('model', 'Mustang'), ('year', 1964)] [20]: list(zip(['brand', 'model', 'year'], ['Ford', 'Mustang', 1964])) # creates a ␣ a collection of k->v pairs. Dictionaries (or associate arrays) provide a structure to lookup values based on keys. I.e. they’re 4.01 Dictionaries 1.3 [19]: '[1, 4.5]' [19]: str([1, 4.5]) [18]: '(1, 2, 3)' [18]: str((1, 2, 3)) [17]: (1, 2, 3, 4) [17]: tuple([1, 2, 3, 4]) int, float, str, list, tuple, dict, ... For casting objects, python provides several functions closely related to the constructors bool, False True Python provides a rich standard library with many builtin functions. Also, bools/ints/fmoats/strings have many builtin methods allowing for concise code. One of the most useful builtin function is help . Call it on any object to get more information, what methods it supports. [16]: s = 'This is a test string!' print(s.lower()) print(s.upper()) print(s.startswith('This')) print('string' in s) print(s.isalnum()) this is a test string! THIS IS A TEST STRING! True 3 ֒ → list of tuples by "zipping" two list

[21]: # convert a list of tuples to a dictionary [27]: # adding a new key D.keys() [32]: # returning a list of keys [31]: True 'brand' in D [31]: # checking whether a key exists [30]: {'brand': 'Ford', 'model': 'Mustang', 'price': '48k'} [30]: D del D['year'] [29]: # removing a key [28]: {'brand': 'Ford', 'model': 'Mustang', 'year': 1964, 'price': '48k'} [28]: D D['price'] = '48k' # help(dict) D = dict(zip(['brand', 'model', 'year'], ['Ford', 'Mustang', 1964])) [26]: # dictionaries have serval useful functions implemented [25]: {'brand': 'Ford', 'model': 'Mustang', 'year': 1964} [25]: D [24]: D = {'brand' : 'Ford', 'model' : 'Mustang', 'year' : 1964} Dictionaries can be also directly defjned using { ... : ..., ...} syntax [23]: 'Mustang' D['model'] [23]: D = dict([('brand', 'Ford'), ('model', 'Mustang')]) [22]: 'Ford' [22]: D['brand'] [21]: {'brand': 'Ford', 'model': 'Mustang', 'year': 1964} D 4

[32]: dict_keys(['brand', 'model', 'price']) [37]: for k, v in D.items(): [39]: (-7.0, 1.5) quadratic_root(*args) [39]: args=(1, 5.5, -10.5) [38]: (-7.0, 1.5) [38]: quadratic_root(1, 5.5, -10.5) into keyword arguments. a tuple or dictionary. I.e. * unpacks a tuple into positional args, whereas ** unpacks a dictionary Python provides two special operators * and ** to call functions with arguments specifjed through 4.02 Calling functions with tuples/dicts 1.4 price: 48k model: Mustang brand: Ford print(' {} : {} '.format(k, v)) 48k [33]: # casting to a list Mustang Ford print(v) [36]: for v in D.values(): price model brand print(k) for k in D.keys(): [35]: # iterating over a dictionary [34]: {'brand': 'Ford', 'model': 'Mustang', 'price': '48k'} [34]: D [33]: ['brand', 'model', 'price'] list(D.keys()) 5

[40]: args=('Tux',) # to create a tuple with one element, need to append , ! [43]: 2 in S set intersection via & or intersection [46]: ({1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}) [46]: {1, 2, 3} | {4, 5}, {1, 2, 3}.union({4, 5}) set union via + or union [45]: ({1}, {1}) [45]: {1, 2, 3} - {2, 3}, {1, 2, 3}.difference({2, 3}) set difgerence via - or difference [44]: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 65, 19] list(set(L)) L = [1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 2, 5, 3, 65, 19] [44]: # casting can be used to get unique elements from a list! [43]: True [42]: {1, 2, 3, 4} kwargs={'message' : 'Hi {} !'} S [42]: S = {1, 2, 3, 1, 4} [41]: set type(S) [41]: S = set() Note: x={} defjnes an empty dictionary! To defjne an empty set, use using {...} . python has builtin support for sets (i.e. an unordered list without duplicates). Sets can be defjned 4.03 Sets 1.5 Hi Tux! greet(*args, **kwargs) 6

[47]: {1, 5, 3, 4} & {2, 3} [51]: # if else must come before for [53]: [7, 3, 2, 10, 0, 2, 3, 3, 5, 5] [random.randint(0, 10) for i in range(10)] [53]: import random [52]: {'apple': 5, 'pear': 4, 'banana': 6, 'cherry': 6} length_dict length_dict = {k : len(k) for k in L} [52]: L = ['apple', 'pear', 'banana', 'cherry'] of the same type. The same works also for sets AND dictionaries. The collection to iterate over doesn’t need to be [51]: [None, (4, 'pear'), (6, 'banana'), (6, 'cherry')] [(len(x), x) if len(x) % 2 == 0 else None for x in L] # ==> here ... if ... else ... is an expression! [50]: [(6, 'banana'), (6, 'cherry')] [47]: {3} [(len(x), x) for x in L if len(x) > 5] [50]: # special case: use if in comprehension for additional condition [49]: [(1, 'apple'), (1, 'pear'), (1, 'banana'), (1, 'cherry')] [(1, x) for x in L] L = ['apple', 'pear', 'banana', 'cherry'] [49]: # list comprehension comprehension expression. This is especially useful for conversions. Instead of creating list, dictionaries or sets via explicit extensional declaration, you can use a 4.04 Comprehensions 1.6 [48]: {3} [48]: {1, 5, 3, 4}.intersection({2, 3}) 7

[54]: {random.randint(0, 10) for _ in range(20)} [58]: fun = make_plus_one( lambda x: x) return y y += a * xq for a in p: xq = 1 y = 0 return 0. if 0 == len(p): def f(x): [59]: def make_polynomial(p): [54]: {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10} [58]: (3, 4, 5) fun(2), fun(3), fun(4) A more complicated function can be created to create functions to evaluate a polynomial defjned return inner Nested functions + decorators [55]: [(k, v) for k, v in length_dict.items()] [55]: [('apple', 5), ('pear', 4), ('banana', 6), ('cherry', 6)] [56]: # filter out elements from dict based on condition {k : v for k,v in length_dict.items() if k[0] < 'c'} [56]: {'apple': 5, 'banana': 6} 1.7 5.01 More on functions ==> Functions are fjrst-class citizens in python, i.e. we can return them return f(x) + 1 [57]: def make_plus_one(f): def inner(x): 8 through a vectpr p = ( p 1 , ..., p n ) T n ∑ p i x i f ( x ) = i =1 xq *= x

return f [65]: greet('Tux').upper() return inner return f(*args, **kwargs).upper() def inner(*args, **kwargs): [68]: def make_upper(f): with a wrapper we could create an upper version [67]: 'THE ONE AND ONLY ANSWER TO … IS 42!' [67]: state_an_important_fact().upper() return 'The one and only answer to ... is 42!' [66]: def state_an_important_fact(): However, what if we want to apply uppercase to another function? ==> however, we would need to change this everywhere [65]: 'HELLO TUX!' Let’s say we want to shout the string, we could do: [60]: poly = make_polynomial([1]) [64]: 'Hello Tux!' [64]: greet('Tux') return 'Hello {} !'.format(name) [63]: def greet(name): ==> we basically decorate the function with another, thus the name decorator We can use this to change the behavior of functions by wrapping them with another! functions scope. When returning them, a closure is created. Basic idea is that when declaring nested functions, the inner ones have access to the enclosing [62]: 4 quad_poly(1) [62]: quad_poly = make_polynomial([1, 2, 1]) [61]: 1 [61]: poly(2) 9

Recommend

More recommend