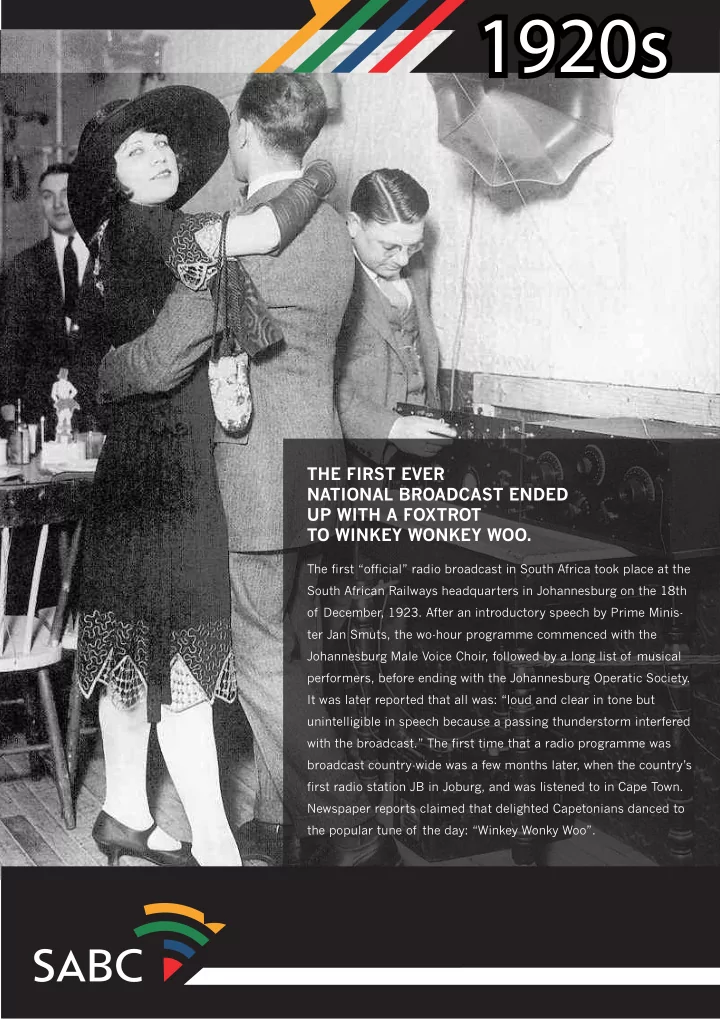

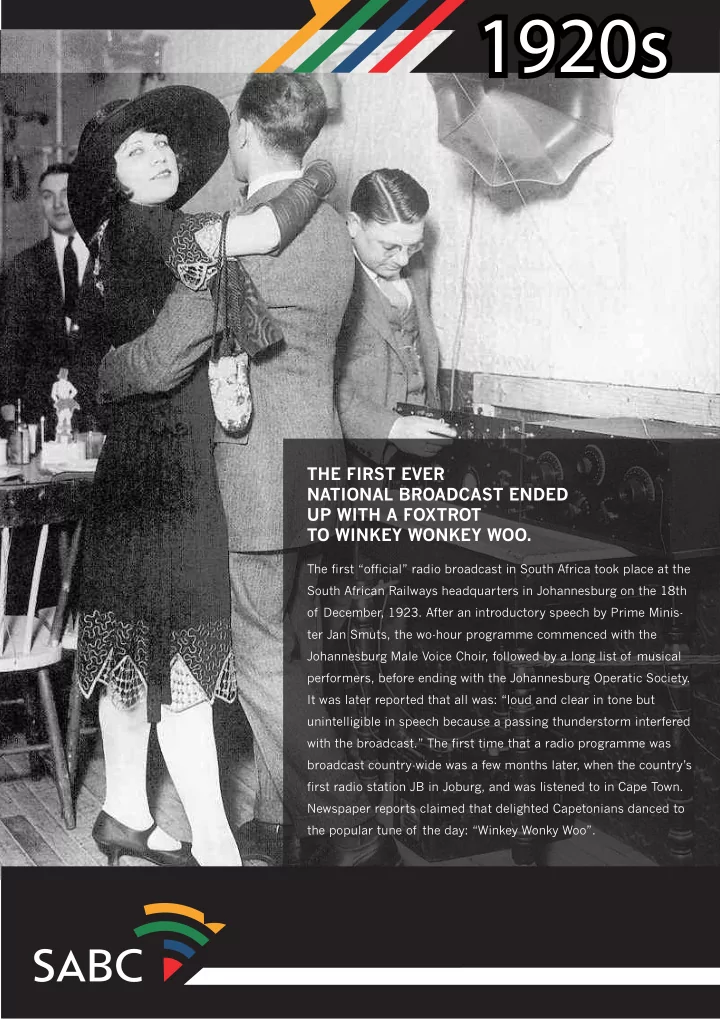

THE FIRST EVER NATIONAL BROADCAST ENDED UP WITH A FOXTROT TO WINKEY WONKEY WOO. The first “official” radio broadcast in South Africa took place at the South African Railways headquarters in Johannesburg on the 18th of December, 1923. After an introductory speech by Prime Minis- ter Jan Smuts, the wo-hour programme commenced with the Johannesburg Male Voice Choir, followed by a long list of musical performers, before ending with the Johannesburg Operatic Society. It was later reported that all was: “loud and clear in tone but unintelligible in speech because a passing thunderstorm interfered with the broadcast.” The first time that a radio programme was broadcast country-wide was a few months later, when the country’s first radio station JB in Joburg, and was listened to in Cape Town. Newspaper reports claimed that delighted Capetonians danced to the popular tune of the day: “Winkey Wonky Woo”.

IN THE 1930S, RADIO MEANT DINNER JACKETS AND OPERETTAS, BUT NO LADIES, TOILETS OR SECOND TAKES. As the SABC was being established, the pompousness of the English Service was notorious: “In the English Service, the human female is a woman and not a lady” “In the English Service, people die; they do not pass on or pass away” “In the English Service, people go to the lavatory or the WC, perhaps permissibly the loo, but not the toilet” Announcers, news readers and presenters, only males, of course, were required to wear dinner jackets for all programmes broad- casted in the evenings. But, as it was long before the tape recorder was invented, everything was performed on a one-take basis!

WHY THE FIRST BLACK VOICE ON RADIO MUST NEVER BE SILENCED. One of the most important developments at the SABC during the war years was the introduction of African language programmes which started in 1941. Up to that point, the black population of South Africa had been completely ignored as an audience by the government. The first direct transmissions to a black audi- ence were made over telephone lines and relayed to certain townships. These allowed for broadcasts to be made in isiZulu, isiXhosa and Sesotho, and they carried news, both local and, of course, news of the war effort. The first transmission was a three-minute news bulletin in isiZulu read by a gentleman who would have a huge impact on South African radio for many years to come: King Edward Masinga. Masinga – a broadcasting genius - went on to have a stellar career as a producer, director, actor, singer and collector of traditional music. He was also a playwright with a prodigious output that included dozens of original radio dramas, as well as several Shakespeare plays that he translated into Zulu.

DURING WORLD WAR II WE CARRIED MILLIONS TO THE BATTLEFRONT . With South African troops making their way North to fight Mussolini’s army in East Africa, the SABC sent three mobile broadcast units, with teams of sound engineers and correspond- ents. Based on army trucks, the units were stripped and rebuilt into self-contained mobile recording units by SABC engineers. Inside, the equipment included two turntables and a cutting lathe that would enable the sounds of the war to be recorded on acetate discs, with electrical power being produced from two ordinary car batteries. These mobile units that travelled the length and breadth of North Africa, and later Italy and Germany so the 334 000 SA troops could stay in touch with loved ones at home.

WHY THE APARTHEID AUTHORITIES WENT TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH TO STOP BLACK PEOPLE LISTENING TO JAZZ The modern jazz of the day had little success getting airtime, as the SABC stubbornly stuck to its preference for traditional African music, which was considered far less subversive than jazz. To build its source of traditional material, the SABC commissioned a major project which involved sending teams of technicians to all corners of the country to record traditional African music. Tribal chiefs, school principals and missionaries were persuaded to recruit local musicians and choirs to perform for the technical team to record. This project was headed up by Mr Kosie Jooste who was in charge of “Native Broad- casts” at the SABC. Jooste and his sound engineers explored huge expanses of the country in fully-equipped SABC vans. Other than great entertainment for listeners, these recordings would also become an invalua- ble archive of traditional African music. Today, some 40 000 vinyl records are stored in the SABC Radio Archives, and are waiting to be digitised.

“WANTED: IMAGINATIVE BANTU YOUTH WITH IMPECCABLE PRONUNCIATION” As Radio Bantu proved so popular, the SABC’s first Bantu authorities require the personnel serving each need was to recruit black people to fill positions at Bantu region to belong to the language group of the various stations. Then, as the radio station’s that region. insatiable demand for content grew, writers, musi- cian, composers and actors were given opportunities “On a personal level a successful candidate needed that they had never previously enjoyed. a lively disposition and the ability to improvise as well as having qualities of inventiveness and imagi- In its move to recruit qualified black personnel as nation. Difficult situations often arise when the radio announcers, the SABC ran an article in the announcer had to call on his own resourcefulness to Bantu Education Journal of November, 1960: “Radio fill-in time unexpectedly.”

WHEN TELEVISION WAS A BIGGER MENACE THAN ATOMIC AND HYDROGEN BOMBS In the early 1970s, South Africans could only look on in Other arguments attempted to hoodwink the public, envy as they were deprived of a television service by a included this rather devious comparison with radio: “TV blinkered government fearful of losing its grip in the demands full attention. It eliminates hobbies, amuse- propaganda war. And the fact that such a spectacle as ments or occupations. Radio offers music and light the first person to set foot on the moon could not be entertainment as a pleasant background to the daily seen on television rankled many. chores or the evening hobby”. Government propaganda, in attempting to influence the However, none were more ridiculous than the claim issue of a television service offered some disingenuous made by the then Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, Dr arguments that TV would not only be far too expensive, Albert Hertzog: “Television as a destroyer of the human and that the viewers would have to foot the bill. spirit is a bigger menace than the atom or hydrogen bomb!”

S’DUMO: THE LOVABLE ROGUE WHO STOLE THE NATION’S HEART . In 1986, the country’s first ever sitcom to be written, produced and directed by black South Africans was broadcast for the first time. “Sgudi Snaysi” was a raucous comedy that starred popular comedy actor Joe Mafela who played the loveable rogue, S’Dumo, who lived as a boarder with Sis May, played by Daphne Hlomu- ka, and her niece Thoko, played by Thembi Mtshali. Another character was the neighbour, Louise, which was played by Gloria Mudau. The recur- ring plot throughout the series always revolved around S’Dumo’s dire financial troubles, and his outrageous antics in trying to turn his financial woes around. Not only was this series one of the longest-run- ning TV sitcoms with 78 hour-long episodes, it was also enjoyed the SABC’s highest ever viewership figures, making it the most popular TV comedy ever on South African TV . As a postscript to the “Sgudi Snaysi” story, in 2002, the series producer, Robert Durrant, was given the rare honour of serving as president of the sitcom jury in the Rose d’Or Festival in Montreux, Switzerland, one of the most prestig- ious award festivals in the TV world.

TWICE HE FAILED MISERABLY , UNTIL HE HIT THE PERFECT NOTE VIR NOTE One of the corporation’s most outstanding success stories, “Noot vir Noot” has produced over 550 episodes, spread over 22-years of broadcasting. This gives the series the distinc- tion of being amongst the top ten longest-run- ning game shows in the world. Conceived and produced by Johan Stemmet and Johan van Rensburg, getting the show off the ground was a bumpy ride. The first series only received a lukewarm response both from the audience and the powers that be at the corpora- tion. But then a second stroke of luck came when another scheduled show ran into production difficulties, and “Noot vir Noot” was given a second lifeline. This time, lessons had been learned. When the show first aired in the early 1990’s it was a time of great political and social upheaval for South Africa, yet “Noot vir Noot” transcend- ed race, class, educational abilities, even language, and it became the quintessential South African show.

Recommend

More recommend