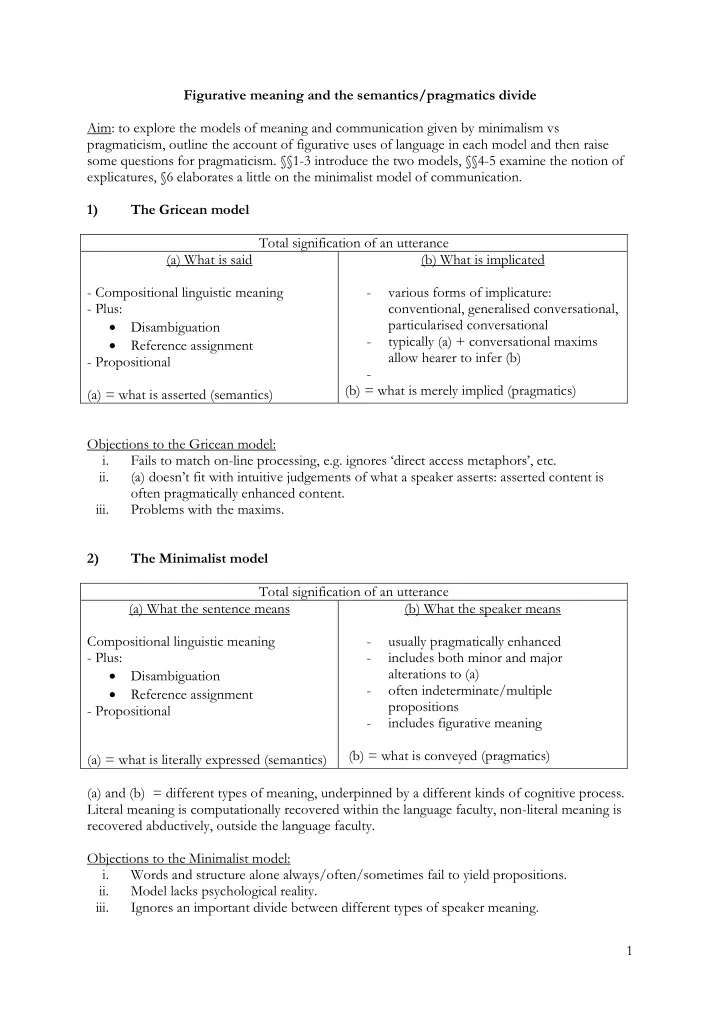

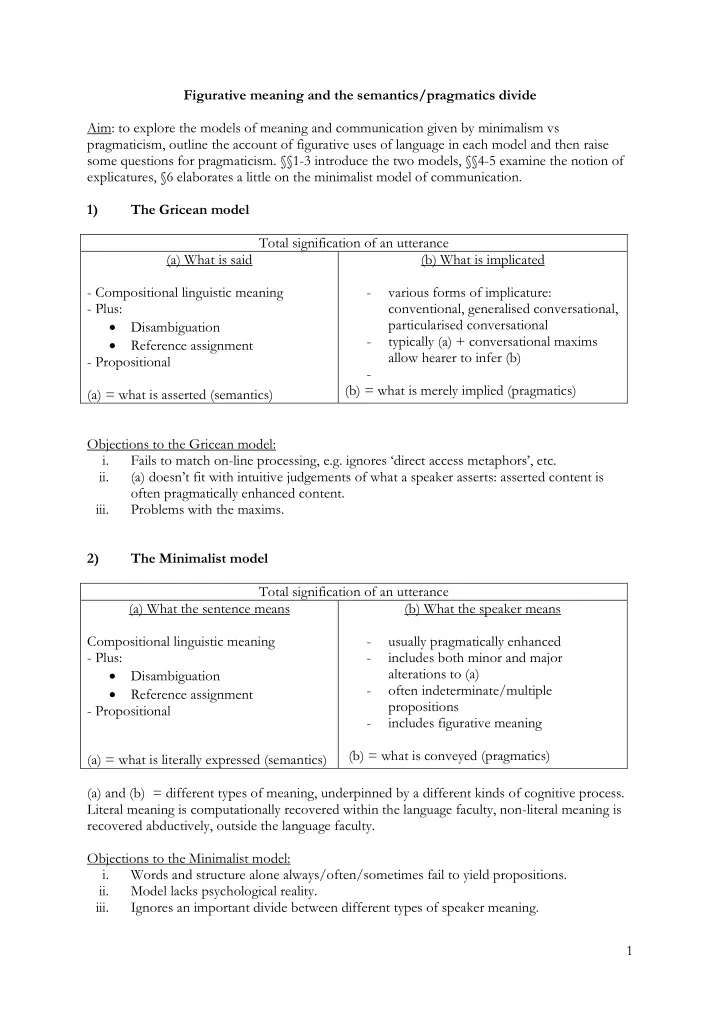

Figurative meaning and the semantics/pragmatics divide Aim: to explore the models of meaning and communication given by minimalism vs pragmaticism, outline the account of figurative uses of language in each model and then raise some questions for pragmaticism. §§1-3 introduce the two models, §§4-5 examine the notion of explicatures, §6 elaborates a little on the minimalist model of communication. 1) The Gricean model Total signification of an utterance (a) What is said (b) What is implicated - Compositional linguistic meaning - various forms of implicature: - Plus: conventional, generalised conversational, Disambiguation particularised conversational - typically (a) + conversational maxims Reference assignment allow hearer to infer (b) - Propositional - (b) = what is merely implied (pragmatics) (a) = what is asserted (semantics) Objections to the Gricean model: i. Fails to match on-line processing, e.g. ignores ‘direct access metaphors’, etc. ii. (a ) doesn’t fit with intuitive judgements of what a speaker asserts: asserted content is often pragmatically enhanced content. iii. Problems with the maxims. 2) The Minimalist model Total signification of an utterance (a) What the sentence means (b) What the speaker means Compositional linguistic meaning - usually pragmatically enhanced - Plus: - includes both minor and major Disambiguation alterations to (a) - often indeterminate/multiple Reference assignment propositions - Propositional - includes figurative meaning (b) = what is conveyed (pragmatics) (a) = what is literally expressed (semantics) (a) and (b) = different types of meaning, underpinned by a different kinds of cognitive process. Literal meaning is computationally recovered within the language faculty, non-literal meaning is recovered abductively, outside the language faculty. Objections to the Minimalist model: i. Words and structure alone always/often/sometimes fail to yield propositions. ii. Model lacks psychological reality. iii. Ignores an important divide between different types of speaker meaning. 1

3) The Pragmaticist model Total signification of an utterance (a) Linguistically encoded (b) explicit content of the (c) what is implicated content utterance: explicature - proposition(s) the speaker directly - further relevant - Compositional linguistic communicates propositions hearers can meaning - an expansion or development of infer on basis of (b) - Always/often/sometimes sub- (a), involving reference assignment propositional. and certain free pragmatic effects (FPEs) (a) = linguistic semantics (b) = what is asserted (c) = what is merely implied 3.1) What is an explicature? i) A pragmatically inferred development of logical form (where implicatures are wholly pragmatically derived); S&W 1986: 182, Carston 2009: 41 ii) What the speaker intends directly to communicate; S&W 1986: 183, Carston 2009: 36 iii) The first content hearers recover via relevance processing; S&W 1986:184-5 iv) The essential premise for inferring further (implicated) propositions; Carston 2009: 41 v) The proposition on which S’s utterance is judged true or false ; Carston 2009: 36 A: ‘How was the party?’ B: ‘There was not enough drink and everyone left’ Explicature: there was not enough alcoholic drink to satisfy the people at [the party] i and so everyone who came to [the party] i left [the party] i early . Implicature: the party was no good. (Carston 2009: 35) Figurative uses: On the RT model there exists a continuum of loose uses, with minor alterations at one end of the scale and metaphor at the other end (or perhaps involving a special, meta-representational process; Carston). Irony is off the scale. “Robert is a computer” Explicature: Robert is a computer* Implicatures: Robert lacks feelings, processes information well… (Wilson 2011: 180) Question: how do we individuate explicatures? 4) Which free pragmatic effects are explicature-generating? 4.1) How many kinds of FPEs? Traditionally theorists have posited two different kinds of FPEs: (i) modulation and (ii) unarticulated constituents (UCs). Why do we need both modulation and UCs? E.g. why treat the location in an utterance of ‘It’s raining’ as an unarticulated constituent as opposed to allowing the meaning of ‘rain’ to be modulated (broadened or narrowed)? Carston and Hall 2012 reject a modulation treatment of the weather predicates, but they do n’t give an argument for this . Since it is unclear what the constraints on broadening/narrowing of senses are, it is unclear whether there remains any role for UCs to play on the pragmaticist model. Without UCs pragmaticism may come to seem more closely al igned to Travis’ occasionalism than it perhaps once did (undermining the idea of ‘developments of LF’? ). 2

4.2) Which FPEs generate explicatures? One of the on-going challenges to any account which wants a special class of free pragmatic effects concerns ho w to restrain them: what stops ‘snow is white’ directly expressing the proposition ‘snow is white & 2+2=4’? In the past, theorists have appealed to: the Availability test (Recanati 1989: 309-10), truth-evaluation tests (Recanati 2004: 15, Noveck et al), the Scope test, and the mechanism of relevance (Carston 2002). However all face problems (see Carston and Hall 2012). For Hall 2008, Carston & Hall 2012 the ‘ultimate arbiter’ of whether or not a pragmatic enrichment contributes to the proposition literally expressed is “the derivational distinction between local and global pragmatic inference” – an effect which modifies a subpart of the linguistically encoded meaning counts as part of the explicature, one which operates on fully propositional forms contributes to implicatures. However, it’s not clear that locality will work as some local enrichments apparently capture implicature content. A: Do you want to have dinner? B: I’m going to the cinema. How should B’s utterance content be modulated? o Narrowed from GOING-TO-THE-CINEMA to GOING-TO-THE-CINEMA- TONIGHT o Narrowed from GOING-TO-THE-CINEMA to GOING-TO-THE-CINEMA- AT-A-TIME-THAT-MAKES-HAVING-DINNER-WITH-A-IMPOSSIBLE Both of these are local effects, but only on the first will it be an implicature of what B says that she cannot have dinner with A (on the second it looks like something she directly asserts). Perhaps the problems with constraining FPEs is instructive. Perhaps we should simply reject the idea that there is a special category of ‘pragmatic developments of logical form’ (i.e. explicatures) which play an inferential role in recovery of other propositions. 5) Do we need the notion of an explicature? i) Explicatures (as developments of LF) need not be psychologically real for speakers. T houghts are just as underdetermined as utterances (if S utters ‘pass me the red pen’ I think she need not, contra Wilson 2011: 181, have internally specified that she wants the pen that writes in red, the one that contains red ink, the one that is red on the lid, the one that says ‘red’ on it, etc; compare ‘ I want to travel to London’. ) ii) Explicatures need not be psychologically real for the audience: all hearers may consciously entertain is ‘ implicature ’ content. iii) As theorists explicatures can play a role in a rational reconstruction of a route from literal meaning to conveyed content, but why should we think hearers must or even typically do follow this route, either explicitly or implicitly? iv) Soliciting judgements of truth/falsity for utterance content is inappropriate, it influences the phenomena it is supposed to be uncovering (‘ quantum effect ’): Under what circumstances is B ’s utterance above true? there wasn’t enough alcoholic drink and so everyone at the party left early But: Is the utterance true in a situation where there was a lot of wine at the party but it was held in a locked cabinet? And is it required that everyone left early in the evening or early for a party? there wasn’t enough easily available alcoholic drink and everyone at the party left after one hour 3

Recommend

More recommend