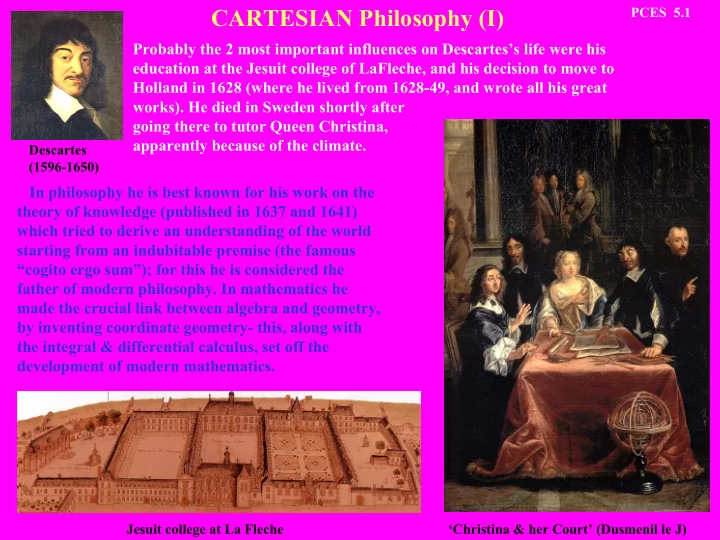

CARTESIAN Philosophy (I) PCES 5.1 Probably the 2 most important influences on Descartes’s life were his education at the Jesuit college of LaFleche, and his decision to move to Holland in 1628 (where he lived from 1628-49, and wrote all his great works). He died in Sweden shortly after going there to tutor Queen Christina, apparently because of the climate. Descartes (1596-1650) In philosophy he is best known for his work on the theory of knowledge (published in 1637 and 1641) which tried to derive an understanding of the world starting from an indubitable premise (the famous “cogito ergo sum”); for this he is considered the father of modern philosophy. In mathematics he made the crucial link between algebra and geometry, by inventing coordinate geometry- this, along with the integral & differential calculus, set off the development of modern mathematics. Jesuit college at La Fleche ‘Christina & her Court’ (Dusmenil le J)

PCES 5.4 The Starry Messenger (I) Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) Galileo was a mathematics professor from Pisa who became famous after the publication in 1610 of ‘Siderius Nuncius’ (the ‘starry messenger’). He was the first to use the newly invented telescope to observe the sky. His very carefully recorded results caused a sensation amongst Galileo’s 1 st telescope only magnified 3 times. However intellectuals in Europe. he was quickly able to make ones with 30x magnification.

PCES 5.5 The Starry Messenger (II) About as powerful than today’s binoculars, his instruments allowed him to discern a multitude of stars beyond the visible. This was already rather troublesome for orthodox belief, since it indicated that the starry firmament was more extensive than previously believed. Giordano Bruno had been burnt at the stake by the inquisition (after a 7-yr trial) for promoting such ideas only 10 Yrs earlier. Galileo’s moon Worse was to come. The Heavenly bodies were held to be perfect by the church, so that the discovery of craters on the moon was a shock to Rome- and it lent further credibility to the ideas of Bruno. Galileo was happy to show the cardinals the view through his looking glass. The region of Orion’s belt & sword (LHS); and the Pleaides (RHS)

PCES 5.6 The Starry Messenger (III) By projecting the sun’s light onto paper, he found It was covered with spots which came and went, and moved with the sun’s rotation. When he turned his telescope on Jupiter the most shattering conclusion came- he found 4 stars associated with it, which moved from night to night in a way that could only be explained by assuming they were in orbit around the planet. At the time Galileo was content, with the example of Bruno in mind, to merely report his results- thereby avoiding Bruno’s fate. 1 st observation of Jupiter’s 4 major moons (the ‘Galilean satellites’) Galileo’s sun (with changing sunspots)

PCES 5.7 Galileo vs. the Inquisition (I) Although Galileo did not hide his opinions after the publication of his observations in 1610, he was not so foolish as to publish these. However in 1632, emboldened by the election of Urban VIII as Pope, he published his famous set of dialogues, in which the 2 world systems (Copernican and Aristotelian) are compared. The role of the Aristotelian was taken by Simplicius, who discussed the questions Salviati and Sagredo One of Galileo’s later Motion of the earth around telescopes the sun, according to Galileo (from the “dialogue”). The essential purpose of the dialogues was to demonstrate the superiority of the Copernican system in its description of the heavens, and also to highlight the deficiencies of the Aristotelian system in its discussion of dynamics. Thus the book (a rather long one) is written deliberately in the form of a philosophical dialogue, reminiscent of Socrates. The emphasis on the results of experimental science, as opposed to ‘first principle’ arguments, is a notable feature of this and earlier writings of Galileo.

PCES 5.8 Galileo vs the Inquisition (II) Galileo’s book sold out. 5 months later, Galileo was called before the Holy Office & tried by the Inquisition. Under threat (cf. G. Bruno) he was forced to recant, and kept under house arrest for the rest of his life. At the end of the 20 th century, 360 yrs later, the Church admitted its G. Bruno (1548-1600) mistake. Trial of Galileo (1632)

‘Discourses & Demonstrations concerning 2 New PCES 5.9 Sciences’, by Galileo Galilei ( Leiden, 1638) Galileo did not waste his time between 1633 and 1642 (when he died, by then blind for 4 yrs). With the help of a disciple (Viviani) he organized his work over a period of 40 yrs, and systematized it into a description of experimental philosophy and its results. This included a discussion of the results of his many experimental investigations of the dynamics of moving bodies, and the underlying principles he thought he had found. It is hard to appreciate now what a mammoth task he had set himself. It involved an emancipation from the idea that one attempted to understand the world starting from a priori principles- which required not only ideas but new tools (such as the clock shown at left). For Galileo’s dynamics, see the COURSE NOTES

PCES 5.2 Descartes’ Scientific Work (I) Descartes also did much scientific work, both in optics and human anatomy. The impact of this work was greatly blunted because he refrained from publishing most of it (it was published after his death). The work was written in the period 1629-33, but he stopped the work almost as it was finished when he heard of the trial and condemnation of Galileo. The optical work is interesting because he gave correct explanations of many optical phenomena (including the rainbow- see figure below left). He understood the laws governing refraction already in 1627 (although they had previously been discovered by Snell in 1620), and his mathematical talents enabled him to deduce many of their complex consequences, starting from the basic formulation shown above. Descartes also tried to give a general theory of dynamics, both for objects on earth and in the heavens- this is discussed in more detail in the course notes. Although his ideas were very persuasive at the time, the methodology is now viewed as fundamentally flawed. This is because despite the apparent generality of the principles he promoted, there was never any attempt to give a quantitative application of them to, eg., planetary motions- from this point of view he was no better than the Greeks. In the end his views were quite incorrect.

PCES 5.3 Descartes’ Scientific Work (II) Descartes’ interest in human anatomy proceeded partly from his interest in perception, and partly from his desire to understand the relation between mind and matter- a dichotomy which Descartes formulated, and which has been uncritically accepted by much of the world since. His understanding of optics allowed him to unravel the some of mechanisms involved in visual perception, as we see in the drawings taken here from his “Treatise on Man”. Notice also his interest in the brain as the organ connected with Perception, memory, etc (but not the ‘soul’). His main object in this work was to show how one could give a mechanistic understanding of physiological processes- although most of these processes, from respiration and digestion to reproduction, were already known in some detail, they had been explained in terms of ‘souls’, instead of mechanically. This was an important step forward.

Recommend

More recommend