Behavioral Economics: Lessons from Retirement Research for Health Care and Beyond A Presentation by CBO Director Peter Orszag to the Retirement Research Consortium August 7, 2008 It’s a great pleasure for me to be with you at the Retirement Research Conference. In my remarks today, I’d like to build on some of the terrific work by researchers in the area of savings and retirement (a good part of which was done by the people in this room), drawing on insights from behavioral economics. I’ll describe some of the les- sons that come from that work and then aim to convince you that much more work awaits in the critical arena of health economics. Decisions About Saving and Behavioral Economics With the help of research in behavioral economics, we have, in recent years, made major strides in understanding how people make decisions about saving and retire- ment. Research now demonstrates what many people who aren’t economists always knew: that when it comes to complex choices such as whether to save and when to retire, people’s decisions are often influenced by social norms and the presentation of their options—in addition to the “substance” of the options themselves. Behavioral economics has suggested ways to change how such choices are presented in order to help improve decisionmaking without necessarily constraining choice. Those sugges- tions—particularly regarding the automatic enrollment of workers in employer-pro- vided savings plans—are beginning to see widespread adoption. This trend represents a tangible example of how economic research can be rapidly translated into concrete policy changes that should improve people’s lives. The Utility of Defaults Let me start by describing a few key insights from behavioral economics on defaults and their implications for policy on saving and retirement. Inertia, it turns out, is a powerful force in decisionmaking, so people tend to stick with a default, even when they can, at very low cost, pick another option. A number of studies have compared participation rates in employer-sponsored retire- ment plans when enrollment is automatic and when employees must act to become

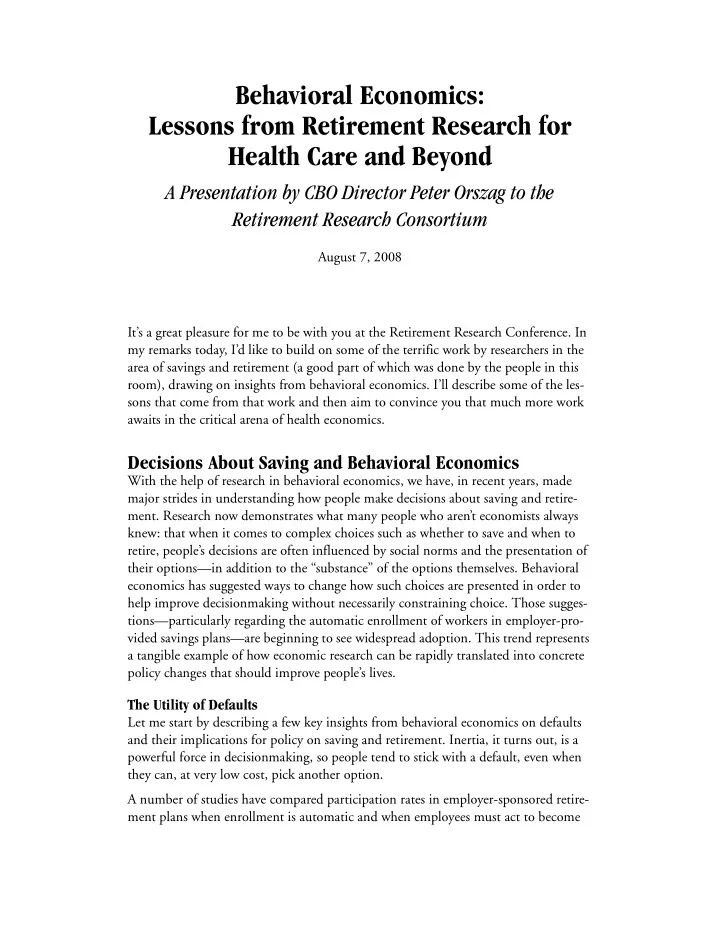

Figure 1. The Effect of Automatic Enrollment on Initial Participation Rates in Companies with 401(k) Plans (Percent) 100 Without Automatic Enrollment With Automatic Enrollment 80 60 40 20 0 All Workers Income Less Than $30,000 Source: Congressional Budget Office based on William E. Nesmith, Stephen P . Utkus, and Jean A. Young, “Measuring the Effectiveness of Automatic Enrollment,” Vanguard Center for Retirement Research, vol. 31 (2007). enrolled. 1 The studies find that automatic enrollment dramatically increases partici- pation rates, especially for subgroups, such as those with low income, for which par- ticipation is otherwise very low. The differences exist despite the fact that workers can easily opt out of the default arrangement. In one recent study, 45 percent of newly hired workers participated in a 401(k) plan when doing so required opting in, but 86 percent did so when enrollment was auto- matic (see Figure 1). For workers making less than $30,000, the difference in partici- pation rates was even larger: 25 percent when workers had to opt in and more than triple that, 77 percent, when they were automatically enrolled. 2 1. For instance, see John Beshears and others, “The Importance of Default Options for Retirement Saving Outcomes: Evidence from the USA,” in Stephen J. Kay and Tapen Sinha, eds., Lessons from Pension Reform in the Americas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 59–87; William G. Gale, J. Mark Iwry, and Peter R. Orszag, “The Automatic 401(k): A Simple Way to Strengthen Retirement Saving” (Washington, D.C.: Retirement Security Project, 2005); Brigitte C. Madrian and Dennis F. Shea, “The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behav- ior,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 116, no. 4 (2001), pp. 1149-1187; and William E. Nesmith, Stephen P . Utkus, and Jean A. Young, “Measuring the Effectiveness of Automatic Enroll- ment,” Vanguard Center for Retirement Research, vol. 31 (2007). 2. Nesmith, Utkus, and Young, “Effectiveness of Automatic Enrollment,” p. 8. 2 CBO

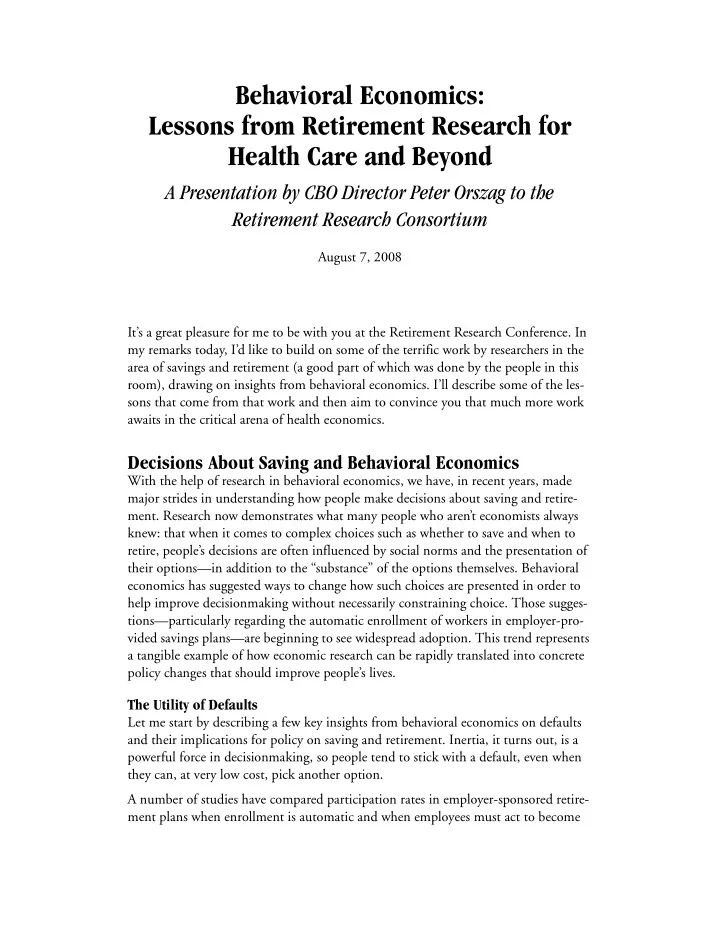

Figure 2. Share of 401(k) Plans Featuring Automatic Enrollment (Percent) 60 50 40 30 Companies with 5,000 or More Eligible Employees All Companies 20 10 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Source: Congressional Budget Office based on data from Profit Sharing/401k Council of America, Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans. Results such as those have prompted rapid adoption of automatic enrollment in 401(k) plans. In 2003, only about 8 percent of 401(k) plans featured automatic enrollment, but by 2007, the number had risen to about 36 percent (see Figure 2). For large retirement plans, the share is even higher. As of 2007, 51 percent of 401(k) plans with 5,000 or more eligible employees offered automatic enrollment. 3 Defaults could be used to not only encourage participation in savings plans but also increase the rate at which participants save, which may have particular application for automatic-enrollment plans. Such plans tend to feature relatively low default contri- bution rates, averaging about 3 percent of pay. 4 Those defaults, it has been shown, tend to anchor people at an inadequate savings rate, including people who, in the absence of a default, would have saved more. 5 But plans could automatically increase the savings rate over time, requiring people to opt out if they wished to avoid the increases. For example, Richard Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi have proposed a plan 3. Profit Sharing/401k Council of America, Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans. 4. Wells Fargo and Bryan, Pendleton, Swats and McAllister, S trategic Initiatives in Retirement Plans: 2007 Survey Analysis (2007), p. 6. 5. For instance, see James J. Choi and others, “For Better or for Worse: Default Effects and 401(k) Savings Behavior,” in David A. Wise, ed., P erspectives on the Economics of Aging (Chicago: Univer- sity of Chicago Press, 2004), pp. 94–107. 3 CBO

called “Save More Tomorrow,” which automatically increases savings rates whenever employees receive a raise. 6 Such an approach harnesses the power of inertia. It also ensures that the automatic increases never result in reduced disposable income, thus recognizing the strong aversion most people feel toward anything they can character- ize as “a loss.” This mechanism has been shown to substantially increase savings rates among participants. As of 2007, about 33 percent of the 401(k) plans that offered automatic enrollment also offered some form of automatic escalation in savings rates, up from about 9 percent only three years before. 7 Use of automatic enrollment and automatic escalation of savings rates should increase further in the wake of the Pension Protection Act of 2006, which provides liability protection and additional incentives to encourage adoption of these defaults. Changes in other defaults could also improve outcomes for a number of other deci- sions related to saving and retirement. For example: B Automatic Individual Retirement Accounts. About half of U.S. workers do not have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan. To aid them, some researchers have suggested automatic IRAs (individual retirement accounts), whereby compa- nies that do not have an employer-sponsored retirement plan can, unless workers opt out, directly deposit some share of employees’ salaries. 8 B Automatic Investment Portfolios. Extensive research in behavioral economics has found that people often act irrationally in picking their investment portfolio. 9 One way to overcome such failures in decisionmaking is for companies to set default investment portfolios that are rationally diversified, unless workers choose to select their own investments. The Pension Protection Act has taken a step in that direc- tion, by establishing incentives for employers to use what are termed “qualified default investment alternatives” for employees automatically enrolled in defined- contribution plans. B Automatic Annuitization. In order to prevent retirees from running out of assets late in life, one proposal would automatically annuitize a substantial portion of an employee’s 401(k). It would allow employees to opt out of the arrangement and receive a lump-sum payment within the first two years of receiving income from the annuity. 10 6. Richard H. Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi, “Save More Tomorrow”: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 112, no. 1 (2004), pp. 164–187. 7. Profit Sharing/401k Council of America, Annual Survey. 8. J. Mark Iwry and David C. John, Pursuing Universal Retirement Security Through Automatic IRAs (Washington, D.C.: Retirement Security Project, 2007). 9. For a useful overview of people’s failures in allocating assets, see Richard H. Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi, The Behavioral Economics of Retirement Savings Behavior (Washington, D.C.: AARP Pub- lic Policy Institute, 2007), pp. 6–17. 10. William G. Gale and others, Increasing Annuitization in 401(k) Plans with Automatic Trial Income (Washington, D.C.: Retirement Security Project, 2008). 4 CBO

Recommend

More recommend