Banks, Government Bonds and Default: What do the Data Say? Nicola - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Banks, Government Bonds and Default: What do the Data Say? Nicola Gennaioli, Alberto Martin and Stefano Rossi Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue December 13, 2016 GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 1 / 32

Banks, Government Bonds and Default: What do the Data Say? Nicola Gennaioli, Alberto Martin and Stefano Rossi Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue December 13, 2016 GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 1 / 32

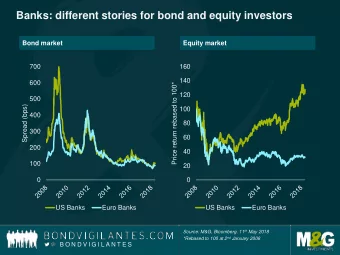

Introduction What are the costs of sovereign risk/defaults? � Recent emphasis on importance of banking channel Center stage during recent European crisis � Europe’s troubled banks and broke governments are in a dangerous embrace (The Economist, 2011) Different potential channels: � Balance sheet channel: banks hold substantial amounts of government bonds � Safety net channel: banks backed by government guarantees � Macroeconomic channel: austerity policies might hurt economic activity and thus banks GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 2 / 32

This paper Focus on balance sheet channel � Banks hold substantial amounts of domestic government bonds � Liquidity (Bolton and Jeanne 2011, Gennaioli et al. 2014) � Risk-taking (Farhi and Tirole 2015) � Default hurts balance sheets of banks → ⇓ in lending → ⇓ in output Believed to have played major role in recent European crisis Yet scant systematic evidence: existing facts � Aggregate (Gennaioli et al. 2014) � European: based on stress tests 2010-12 and syndicated lending (Popov and Van Horen (2014), De Marco (2016)) � Limited time period, small lending market GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 3 / 32

What we do Analyze sovereign default-bank nexus using bank-level data � Across many countries, periods and default episodes Stylized facts (no causality) Two key questions: � Which banks, in which countries, hold government bonds? � Do they hold bonds all of the time or mostly during sovereign defaults? � Do banks that hold more government bonds reduce their lending the most during defaults? GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 4 / 32

The Data Bankscope database Advantage: wide coverage � Characteristics of over 20.000 banks in 191 countries between 1998-2012 � Bondholdings at the bank level � 20 default episodes: mostly in developing countries Disadvantage: � Does not report nationality of bonds � Domestic or foreign government bonds? GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 5 / 32

Main results Negative, significant correlation between bank’s bondholdings during sovereign default and subsequent lending � $1 increase in bondholdings ⇔ $0.50 decrease in lending � Result robust to controlling for country shocks and bank characteristics Banks hold large amount of government bonds (around 9% of assets) in normal times � In particular, banks that make fewer loans and are located in financially underdeveloped countries � Bondholdings increase slightly during default episodes � Especially in larger (and more profitable) banks Findings consistent with “supply” channel � Banks hold substantial bonds in normal times (liquidity services) � Government defaults hurt banks and reduce lending � Conceptually: result consistent with imperfect discrimination (Broner et al. 2010) GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 6 / 32

Related literature Costs of sovereign defaults � Recent theories based on non-discrimination: collateral damage of defaults � Basu (2010), Broner and Ventura (2011), Brutti (2011), Gennaioli et al. (2014), Mengus (2015), Farhi and Tirole (2015) � Relationship between sovereign risk and private credit � Arteta and Hale (2008), Borensztein and Panizza (2008), Baskaya and Kalemli-Ozcan (2016) Relationship between bank lending and sovereign risk � Acharya and Steffen (2013), Brutti and Saure (2013), Popov and Van Horen (2014), De Marco (2016) Demand for government bonds � Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen (2012), Greenwood and Vayanos (2014) GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 7 / 32

Data sources: bank-level variables Bank-level data from Bankscope dataset (Bureau van Dijk) � Information on broad range of bank characteristics � Suitable for international comparisons because data is harmonized Crucial: Bankscope reports banks’ holdings of government bonds � However, no information on nationality of bonds � Use IMF/EU/Argentine data to validate information Main sample: 7,391 banks in 160 countries, 36,449 bank-year observations � Commercial banks (33.2%), cooperatives (38.2%), savings banks (20.6%), investment banks (1.6%) � Sample construction: filter out � duplicate records � banks with total assets < $100K � years < 1997 � banks without two consecutive years of data GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 8 / 32

Data sources: aggregate variables Macroeconomic conditions: � IMF’s International Financial Statistics (IFS) and WB’s World Development Indicators (WDI) � Proxy financial development with private credit to GDP Sovereign default: � Dummy variable based on Standard and Poor’s � Default is failure to meet principal or interest payment in original terms � Greek bond swap of 2012: default � 19 sovereign defaults in 16 countries � complement analysis with alternative measure of default � “haircuts” (Cruces and Trebesch 2013) � S&P measure “augmented” with spreads GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 9 / 32

Data sources: aggregate variables Supplement Bankscope data with realized and expected bond returns Realized returns: � JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBIG+) for emerging countries, and on JP Morgan’s Global Bond Index (GBI) for developed countries � Kim (2010) and Levy-Yeyati, Martinez-Peria, and Schmukler (2010) Expected returns: problematic, because not observed � construct it through two-step process � first stage: regress returns on country-specific economic, financial and political risk factors R c , t = γ t + β 0 + β 1 Z c , t − 1 + u c , t where � R c , t is realized returns of public bonds in country c at time t � γ t are time-dummies, which capture variations in global risk-free rate � Z c , t − 1 are risk ratings compiled by ICRG, shown to negatively predict returns (e.g. Comelli 2012) � second stage: define expected returns as fitted values of this first-stage regression GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 10 / 32

Sample of sovereign defaults Country Default S&P Haircut No Bank-Years No Banks Argentina 2001-2004 76.8% 231 87 Ecuador 1998-2000 38.3% 32 30 Ecuador 2009 67.7% 8 8 Ethiopia 1998-1999 92.0% 2 1 Greece 2011-2012 64.8% 12 6 Guyana 1998-2004 91.0% 20 3 Honduras 1998-2004 82.0% 79 21 Ireland 7 7 Indonesia 1998-2000; 2002 17 13 Jamaica 2010 5 5 Kenya 1998-2004 45.7% 160 33 Nigeria 2002 41 41 Portugal 12 12 Russia 1998-2000 51.1% 40 31 Serbia 1998-2004 70.9% 2 2 Seychelles 2000-2002; 2010 56.2% 1 1 Sudan 1998-2004 2 1 Ukraine 1998-2000 14.8% 14 7 Venezuela 34 26 Zimbabwe 2000-2004 6 3 No Banks 725 338 No Countries 16 11 No Episodes 19 12 GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 11 / 32

Data on bondholdings: is it reliable? Compare with IMF aggregate data � Financial Institutions’ Net Claims to the Government (IFS) Average measures look quite similar GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 12 / 32

Data on bondholdings: is it reliable? Compare with bank-level data � European stress tests (2010, 2011, 2012) � Data on domestic bondholdings from Argentine Central Bank (2002-2004) Table I – Bank’s Holdings of Government Bonds from BANKSCOPE and Other Sources The table reports summary statistics of bank bondholdings as a percentage of total assets for selected samples. Sample EU Banks GIIPS Banks Argentine Banks Source BANKSCOPE Stress Test BANKSCOPE Stress Test BANKSCOPE Central Bank Mean 8.16 5.12 9.43 6.22 14.23 11.34 Median 7.68 4.44 8.22 5.64 10.73 8.09 Correlation 0.69 0.76 0.77 Sample Period 2010-2012 2010-2012 1997-2004 No Obs. 126 65 589 No Banks 66 33 142 GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 13 / 32

Descriptive statistics: bondholdings GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 14 / 32

Descriptive statistics: bank characteristics Panel A – Bankscope, Constant-continuing sample Mean Median Std Deviation No Countries No Observations Assets ($/M) 9,922.0 725.6 81,400.0 160 36,449 Non-cash assets 95.8 97.6 5.6 160 36,449 Leverage 91.0 93.3 8.4 160 36,449 Loans 57.1 60.0 17.0 160 36,449 Profitability 0.9 0.7 2.1 160 36,449 Exposure to Central Bank 3.3 1.5 4.9 160 36,449 Interbank Balances 12.2 9.2 12.5 160 36,449 Government Owned 2.5 0.0 15.7 160 36,449 GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 15 / 32

Descriptive statistics: sovereign bond returns Figure 2. Sovereign Bond Prices in Defaulting Countries . The figure plots the average bond prices over 7 default episodes in 6 countries (Argentina 2001-2004, Russia 1998-2000, Cote d’Ivoire 2000-2004, Ecuador 1998-2000, Ecuador 2009, Nigeria 2002, Greece 2012), from day -1,000 to +1,000, whereby day 0 is the day in which default is announced. GMR (Bocconi, CREI, and Purdue) Sovereign Debt and Risks December 13, 2016 16 / 32

Recommend

More recommend

Explore More Topics

Stay informed with curated content and fresh updates.