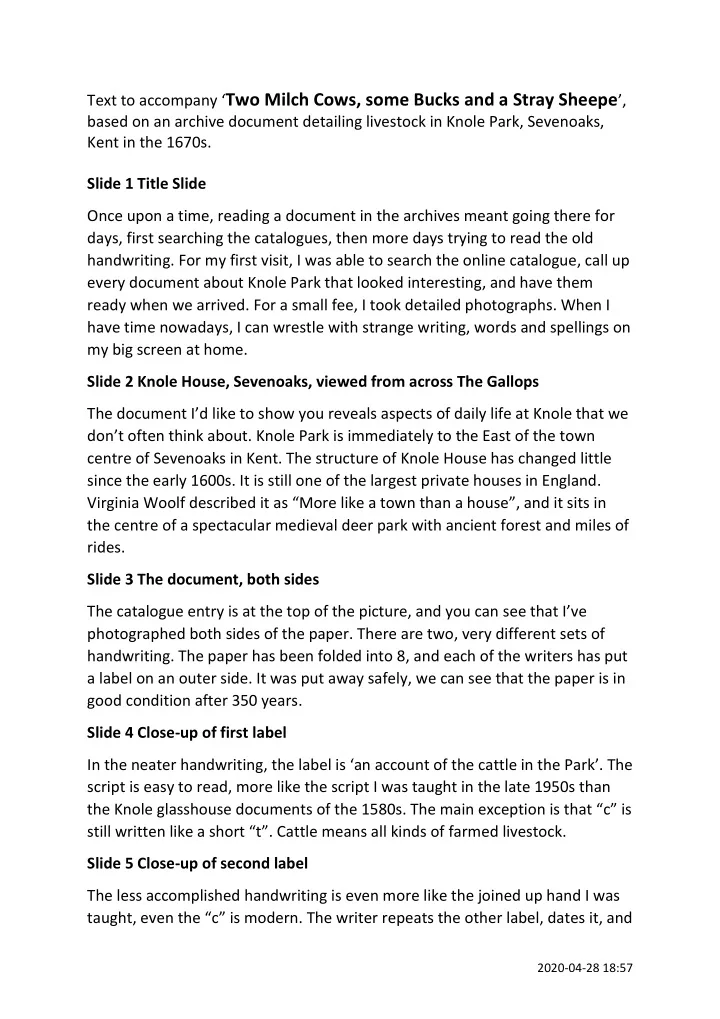

Text to accompany ‘ Two Milch Cows, some Bucks and a Stray Sheepe ’, based on an archive document detailing livestock in Knole Park, Sevenoaks, Kent in the 1670s. Slide 1 Title Slide Once upon a time, reading a document in the archives meant going there for days, first searching the catalogues, then more days trying to read the old handwriting. For my first visit, I was able to search the online catalogue, call up every document about Knole Park that looked interesting, and have them ready when we arrived. For a small fee, I took detailed photographs. When I have time nowadays, I can wrestle with strange writing, words and spellings on my big screen at home. Slide 2 Knole House, Sevenoaks, viewed from across The Gallops The document I’d like to show you reveals aspects of daily life at Knole that we don’t often think about. Knole Park is immediately to the East of the town centre of Sevenoaks in Kent. The structure of Knole House has changed little since the early 1600s. It is still one of the largest private houses in England. Virginia Woolf described it as “More like a town than a house” , and it sits in the centre of a spectacular medieval deer park with ancient forest and miles of rides. Slide 3 The document, both sides The catalogue entry is at the top of the picture, and you can see that I’ve photographed both sides of the paper. There are two, very different sets of handwriting. The paper has been folded into 8, and each of the writers has put a label on an outer side. It was put away safely, we can see that the paper is in good condition after 350 years. Slide 4 Close-up of first label In the neater handwriting, the label is ‘ an account of the cattle in the P ark’ . The script is easy to read, more like the script I was taught in the late 1950s than the Knole glasshouse documents of the 1580s. The main exception is that “c” is still written like a short “t”. Cattle means all kinds of farmed livestock. Slide 5 Close-up of second label The less accomplished handwriting is even more like the joined up hand I was taught, even the “c” is modern . The writer repeats the other label, dates it, and 2020-04-28 18:57

Two Milch Cows, some Bucks and a Stray Sheepe 2 attributes it to Walker. Then a firm slash, which is his separator for items in a list, and his own title, followed by another slash - leaving plenty of room for more lists. Slide 6 The document, both sides, corrected title The catalogue said this was a document from 1661, but it is clearly from 1672 and 3. Turning now to the lists on the main side of the document. Slide 7 The ‘Particular’ We have the neat list entitled “A particular of the cattle that were in my Lord’s Park the 15 th of August 1672 ”. It lists livestock belonging to both “my Lord” , Richard Sackville, 5 th Earl of Dorset and “my Lady” , Frances Cranfield. Slide 8 The whole list page A particular is a detailed account, and the writer seems to have been expecting a lot more livestock to detail, leaving a good space between the two parts of the list, and plenty of space below that. Slide 9 The Particular list The list is carefully set out, with dashed leaders to the numbers of each item and a neat dot over each 1. At the top left is an abbreviation, “ I.m.p squiggle s ” , standing for Imprimis, sometimes Inprimis, meaning ‘ in first place ’ . This was used at the start of a list. In the list are: - Two milch cows of my Lords - The hariot taken of William Keene - Two milch cows of my Ladys - One bull of my Ladys Everything to do with breeding animals was my Lady’s responsibility, so she has the bull. Also everything to do with clothing was my Lady’s , so she has the ten sheep, and, presumably, the wool from the “ One stray sheep ” . Let’s take two of the terms , “milch cow” and “heriot” away for a further look. A milch cow is simply a cow kept for her milk. The other kinds of cattle were draught animals, that is: oxen, and those kept for their beef, mainly bullocks. Slide 10 The Milch Cow of My Lord’s To have their daily fresh pinta, my Lord and my Lady each had to have two milch cows because one couldn’t be kept in milk all year. The milk had to be

Two Milch Cows, some Bucks and a Stray Sheepe 3 the freshest and the finest . I don’t know the breed of the milch cows at Knole in 1672, but Lord Sackville still kept a Jersey in 1954. You might think that my sole reason for making this presentation is to show this picture, I could n’t possibly comment. Slide 11 Origin of Heriot Heriot is a term with Old English origins. It means “war gear”. A local lord would need to have his tenants ready to fight if called upon, but doing productive work most of the time. The tenants couldn’t afford to own protective gear and weapons, especially not a sword. Swords were very expensive and only the really rich could own one, let alone afford to be buried with it. Once the tenant had died, hopefully not on the field of battle, the lord would reclaim his heriot and award it to a new man , maybe the tenant’s heir, to make him war ready. Over time, the heriot became anything the lord loaned to a tenant to equip him for life. Cows were often given as a heriot, possibly when a man married and set up a household. Upon the man’s death, the lord’s steward was entitled to take his pick of the man’s herd . The heriot in the Park had been “taken from William Keene” . Slide 12 List of bucks killed Let’s turn to the second list on the page, crammed in under my Lady’s sheep. It’s written by James Palmer, Deer Keeper, and lists the bucks killed in the buck hunting season of 1673, and the people who received them. The buck hunting season took place when the bucks were “in grease”, plump and well fed on summer grass before the rut. In King Cnut’s early 11 th century 'Charta de Foresta' the buck hunting season was set from the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (24 June) to Holyrood day (14 September), and this was largely adhered to later, not least because in the last weeks before the October rut, rising testosterone levels would taint the meat. Slide 13 List of bucks killed, ink blots highlighted After the last entry was made, the paper was folded before the ink was dry, quite a lot of ink has been printed onto the opposite sides of the sheet in mirror image. “Deer keeper” has been squeezed in later, between the title line and the list itself.

Two Milch Cows, some Bucks and a Stray Sheepe 4 A deer keeper was well paid and provided with a lodge in the Park. One of Palmer’s predecessors left substantial bequests: his own house in Chevening, adjacent land, and £50 (over £100,000 today). The Edmund in the text is likely to have been the underkeeper, and would have been paid as much as an estate bailiff. Slide 14 List of bucks killed, with transcript The list starts with the abbreviation for Inprimis, as before. Instead of a new line for each entry Mr. Palmer has ended them with a firm slash. He starts each one with I t full stop and the squiggle that marks an abbreviation, I t being short for Item, which was usual for lists. Each item has a description of the deer, and the name of the people who received one, starting with “One fallow buck for Major Wildman”. In Royal Forests, venison could not be sold, it could only be a gift, to discourage poaching. This law was also followed beyond the Royal Forests. In the 1500s we have records of gifts of venison from Knole being used as a sweetener at the start of negotiations. Some of the recipients of the bucks killed in 1673 were important local residents with whom the venison helped to keep good, neighbourly relations. Some of them would have hunted the deer themselves, under the watchful guidance of the Deer Keeper. The Keeper prepared the carcase and delivered it to the recipient. Even though it was a gift from the estate, it was the custom to tip the Keeper when he delivered. Around 1625, the going rate was 3s 4d per buck, a week’s wage for a skilled workman. In addition, the Keeper traditionally kept for himself the skin (valuable for sale to clothiers), head, umbles (edible offal), chine (backbone) and shoulder. Slide 15 Expanded transcript of list of bucks killed Foremost among the recipients were Major Wildman, whose title might have been due to a current military role, or carried over from the Civil War, and a name written as Bayekerstaffe, which Google immediately corrected to Bickerstaffe. Sir Charles Bickerstaffe had bought the Stidulfe’s Place estate adjacent to Knole and renamed it ‘Wilderness’. He was an Admiral, a Justice, and corresponded with Samuel Pepys on supplying capstan bars and elm from Wilderness for the navy. Definitely an eminent neighbour with whom the Earl would want to keep on good terms!

Recommend

More recommend