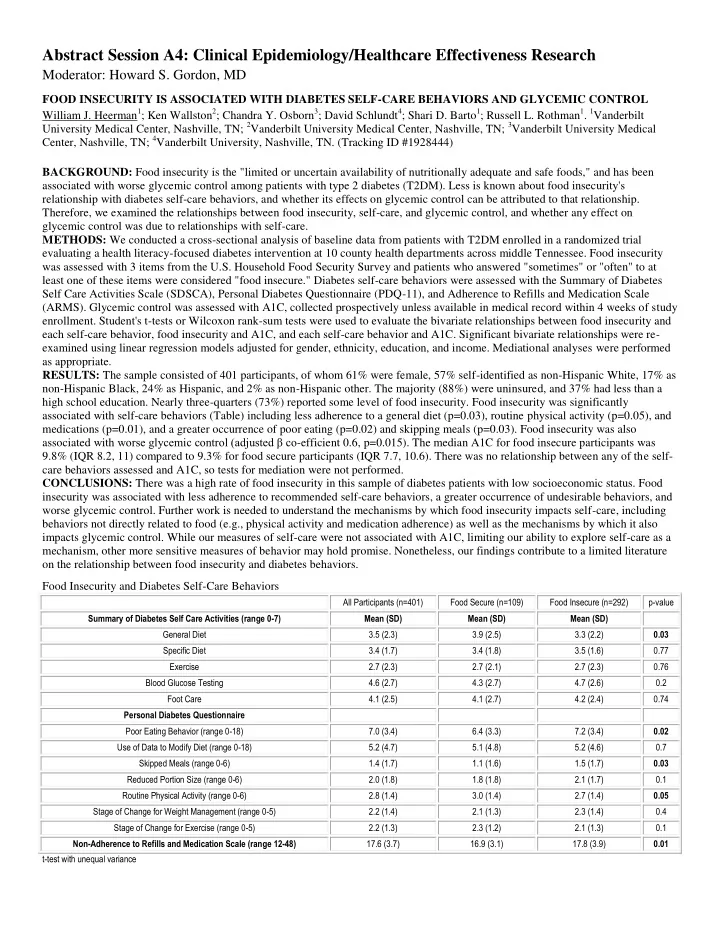

Abstract Session A4: Clinical Epidemiology/Healthcare Effectiveness Research Moderator: Howard S. Gordon, MD FOOD INSECURITY IS ASSOCIATED WITH DIABETES SELF-CARE BEHAVIORS AND GLYCEMIC CONTROL William J. Heerman 1 ; Ken Wallston 2 ; Chandra Y. Osborn 3 ; David Schlundt 4 ; Shari D. Barto 1 ; Russell L. Rothman 1 . 1 Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN; 2 Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN; 3 Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN; 4 Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. (Tracking ID #1928444) BACKGROUND: Food insecurity is the "limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods," and has been associated with worse glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Less is known about food insecurity's relationship with diabetes self-care behaviors, and whether its effects on glycemic control can be attributed to that relationship. Therefore, we examined the relationships between food insecurity, self-care, and glycemic control, and whether any effect on glycemic control was due to relationships with self-care. METHODS: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from patients with T2DM enrolled in a randomized trial evaluating a health literacy-focused diabetes intervention at 10 county health departments across middle Tennessee. Food insecurity was assessed with 3 items from the U.S. Household Food Security Survey and patients who answered "sometimes" or "often" to at least one of these items were considered "food insecure." Diabetes self-care behaviors were assessed with the Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities Scale (SDSCA), Personal Diabetes Questionnaire (PDQ-11), and Adherence to Refills and Medication Scale (ARMS). Glycemic control was assessed with A1C, collected prospectively unless available in medical record within 4 weeks of study enrollment. Student's t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to evaluate the bivariate relationships between food insecurity and each self-care behavior, food insecurity and A1C, and each self-care behavior and A1C. Significant bivariate relationships were re- examined using linear regression models adjusted for gender, ethnicity, education, and income. Mediational analyses were performed as appropriate. RESULTS: The sample consisted of 401 participants, of whom 61% were female, 57% self-identified as non-Hispanic White, 17% as non-Hispanic Black, 24% as Hispanic, and 2% as non-Hispanic other. The majority (88%) were uninsured, and 37% had less than a high school education. Nearly three-quarters (73%) reported some level of food insecurity. Food insecurity was significantly associated with self-care behaviors (Table) including less adherence to a general diet (p=0.03), routine physical activity (p=0.05), and medications (p=0.01), and a greater occurrence of poor eating (p=0.02) and skipping meals (p=0.03). Food insecurity was also associated with worse glycemic control (adjusted β co -efficient 0.6, p=0.015). The median A1C for food insecure participants was 9.8% (IQR 8.2, 11) compared to 9.3% for food secure participants (IQR 7.7, 10.6). There was no relationship between any of the self- care behaviors assessed and A1C, so tests for mediation were not performed. CONCLUSIONS: There was a high rate of food insecurity in this sample of diabetes patients with low socioeconomic status. Food insecurity was associated with less adherence to recommended self-care behaviors, a greater occurrence of undesirable behaviors, and worse glycemic control. Further work is needed to understand the mechanisms by which food insecurity impacts self-care, including behaviors not directly related to food (e.g., physical activity and medication adherence) as well as the mechanisms by which it also impacts glycemic control. While our measures of self-care were not associated with A1C, limiting our ability to explore self-care as a mechanism, other more sensitive measures of behavior may hold promise. Nonetheless, our findings contribute to a limited literature on the relationship between food insecurity and diabetes behaviors. Food Insecurity and Diabetes Self-Care Behaviors All Participants (n=401) Food Secure (n=109) Food Insecure (n=292) p-value Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities (range 0-7) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) General Diet 3.5 (2.3) 3.9 (2.5) 3.3 (2.2) 0.03 Specific Diet 3.4 (1.7) 3.4 (1.8) 3.5 (1.6) 0.77 Exercise 2.7 (2.3) 2.7 (2.1) 2.7 (2.3) 0.76 Blood Glucose Testing 4.6 (2.7) 4.3 (2.7) 4.7 (2.6) 0.2 Foot Care 4.1 (2.5) 4.1 (2.7) 4.2 (2.4) 0.74 Personal Diabetes Questionnaire Poor Eating Behavior (range 0-18) 7.0 (3.4) 6.4 (3.3) 7.2 (3.4) 0.02 Use of Data to Modify Diet (range 0-18) 5.2 (4.7) 5.1 (4.8) 5.2 (4.6) 0.7 Skipped Meals (range 0-6) 1.4 (1.7) 1.1 (1.6) 1.5 (1.7) 0.03 Reduced Portion Size (range 0-6) 2.0 (1.8) 1.8 (1.8) 2.1 (1.7) 0.1 Routine Physical Activity (range 0-6) 2.8 (1.4) 3.0 (1.4) 2.7 (1.4) 0.05 Stage of Change for Weight Management (range 0-5) 2.2 (1.4) 2.1 (1.3) 2.3 (1.4) 0.4 Stage of Change for Exercise (range 0-5) 2.2 (1.3) 2.3 (1.2) 2.1 (1.3) 0.1 Non-Adherence to Refills and Medication Scale (range 12-48) 17.6 (3.7) 16.9 (3.1) 17.8 (3.9) 0.01 t-test with unequal variance

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF A PRACTICE-BASED TRIAL OF BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL IN BLACKS: IS LESS MORE? Antoinette Schoenthaler 1 ; Jeanne Teresi 2 ; Leanne Luerassi 1 ; Stephanie Silver 2 ; Jian Kong 2 ; Taiye Odedosu 1 ; Gbenga Ogedegbe 1 . 1 New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY; 2 The Hebrew Home at Riverdale, Riverdale, NY. (Tracking ID #1929818) BACKGROUND: The efficacy of interventions targeted at comprehensive therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) is well proven in reducing blood pressure (BP) among patients with hypertension (HTN). However their translation to primary care practices is limited, particularly among black patients with HTN, who share a disproportionately greater burden of HTN-related outcomes. More importantly, the comparative effectiveness of single session TLC interventions on BP reduction in primary care practices is unproven. The aim of this vanguard trial was to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of a practice-based comprehensive lifestyle intervention targeted at recommended TLC, delivered through group-based counseling and motivational interviewing (MINT), versus a single session counseling on lifestyle modification (SSC) in reducing BP at six months among low-income, blacks with uncontrolled HTN. METHODS: A total of 194 black patients were randomized to either the MINT-TLC or SSC group. The comprehensive lifestyle intervention (MINT-TLC) was based on established clinical practice guidelines for prevention and treatment of HTN, which recommends weight loss (if overweight), regular physical activity, limiting and/or reducing sodium and alcohol intake, and eating a low-fat diet that is rich in fruit and vegetables. Patients in the MINT-TLC group attended 10 weekly group classes (intensive phase) focused on TLC; followed by 3 monthly individual MINT sessions (maintenance phase) delivered by trained Health Educators. Patients in the SSC condition received a single 30-minute individual counseling session on therapeutic lifestyle changes at the baseline visit by trained study staff. To match the MINT-TLC group for content of intervention material, those in the SSC group also received print versions of the intervention curriculum that was distributed in the group classes. The primary outcome was change in systolic BP and diastolic BP at 6 months assessed with an automated BP monitor (WatchBP). The average of three BP readings was used as the primary outcome measurement, following standard American Heart Association guidelines. The primary analyses examined systolic and diastolic BP separately based on intent-to-treat. A repeated measures mixed model approach was used to account for continuous primary outcomes collected at three waves (baseline, 3 and 6 months), and clustering within primary care providers. The post-treatment values of continuous outcomes were modeled as functions of baseline values, treatment and the interaction of baseline and treatment. RESULTS: The mean age of all patients was 57 years, 50% were women, 69% had income < $20,000/year with mean baseline BP 147.4/89.3 mmHg. Average attendance at the group-based classes in the MINT-TLC condition was 50%; 35% of patients completed all 3 individual MINT sessions. There was non-significant reduction in systolic and diastolic BP for the MINT-TLC compared to the SSC group. The net adjusted reduction in systolic BP by six months was 12.9 mmHg for the SSC vs. 9.5 mmHg for the MINT-TLC group. The reduction in diastolic BP was 7.6 mmHg for the SSC vs. 7.2 mmHg for the MINT-TLC group. CONCLUSIONS: Despite the non-significant between-group difference in BP reduction in the intensive group counseling with multiple office visits versus the single counseling session plus educational material both groups exhibited comparable and clinically meaningful BP reduction. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions in a large Phase 3 trial is warranted in this patient population. Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01070056

Recommend

More recommend